In this post, I shall attempt to get to the nub of a vital but often overlooked point of difference between Intelligent Design theory and some of its Thomist critics. The issue relates to precisely what it is that makes a thing a thing, and not just a virtual imitation of a thing. I’m also going to talk about Harry Potter, so stay tuned.

What I shall attempt to argue is that the concept of “top-down creation” is unintelligible. Things have to also be made from the bottom up: in order to create something, de novo, you have to fully specify what it is that you’re creating. That means filling in all the details.

More generally, what I’m claiming is that in order for a thing to be a genuine entity in its own right (and not just a virtual imitation of an entity), it has to be fully specified, at all levels, from the bottom to the top. Recently, Professor Edward Feser and Professor Chistopher Martin (who are both Thomist philosophers) have maintained that things can be automatically built by God, from the top down, without the need for God to precisely specify their lower-level properties. I claim that this way of making things won’t work, and that an entirely top-down approach to design would rob things of their very “thinghood.” To put it bluntly: if we were made in that way, then we’re not real.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

How Professor Feser thinks God makes things

|

|

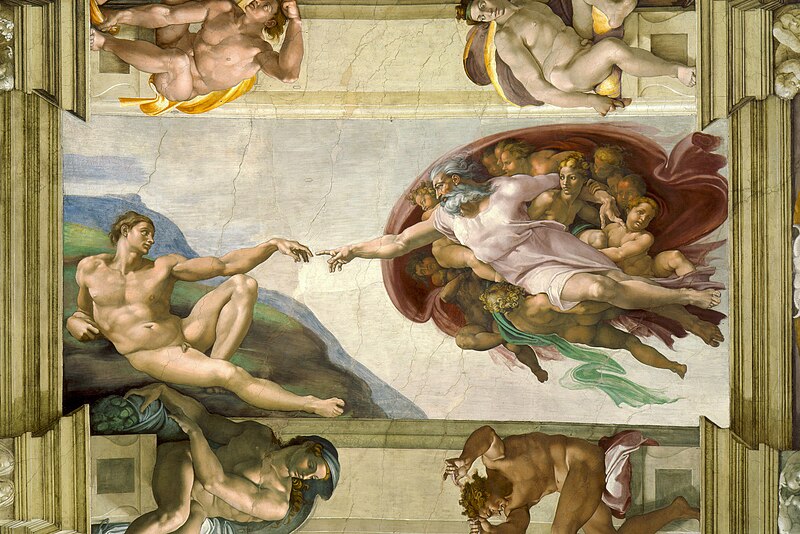

Left: The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo. Sistine Chapel ceiling, circa 1511. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

According to Professor Feser, creation is entirely a top-down process. God can make a man from dust simply by saying, “Dust, become a man.” In so doing, He does not – indeed, could not – achieve His result by tinkering with the dust particles.

I maintain, on the contrary, that in the process of making a man from dust, God would have to rearrange the dust particles from the bottom up, while simultaneously bestowing the substantial form of a man on the underlying (prime) matter. Simply telling dust to become a man fails to specify what kind of man God wants – e.g. how tall he should be, what blood type he should have, what kind of face he should have, and so on. It also fails to specify the micro-level properties of the man in question – e.g. how many cells his body should have, and exactly what sequence of bases he should have in his DNA.

Right: A hotel suite. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dr. David Bowman is transported through space to what looks like a hotel suite. Bowman soon realizes, however, that the suite is a facade, constructed to make him feel at ease. He discovers this when he finds that the “things” in the suite only bear a superficial resemblance to the real-life objects that they were designed to replicate. For instance, the books in the suite have recognizable titles, but are empty inside. There’s a refrigerator and familiar looking boxes of food. Inside the boxes, though, there is only a blue goo that resembles a pudding. In short: it is the lack of specificity of the items in the suite, at the finer level of detail, that makes Dr. Bowman realize that they are not real objects but replicas. The point I wish to make in this section is to argue that in order for something to be a real natural object, it has to be fully specified, all the way down to the bottom level. Where I part company with Professor Feser is that he seems to believe that God can dodge the “specificity problem”: when He makes something, He doesn’t have to specify its details, all the way down. I maintain that He does.

In a post entitled, ID theory, Aquinas, and the origin of life: A reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), Professor Feser spelt out exactly what he believes happens when God creates something:

…[W]hether or not we think of God as specially creating life in an extraordinary intervention in the natural order, the way He creates is not properly understood on the model of human artifice. He does not make a living thing the way a watchmaker makes a watch or the way a builder builds a house. He does not take pre-existing raw materials and put them into some new configuration; nor does He even create the raw materials while simultaneously putting the configuration into them. (As I’ve said before, temporal considerations are not to the point.) Rather (as I put it in my earlier post) he creates by conjoining an essence to an act of existence, where the essence in question is a composite of substantial form and prime matter. That is the only way something that is “natural” rather than “artificial” in Aristotle’s technical senses of those terms possibly could be created.

In a comment on another post, entitled, Nature versus Art (April 30, 2011), Professor Feser also asserted that God could, if He wished, make a man from the dust of the ground, simply by saying, “Dust, become a man.” As he wrote back to me, when I asked him about the sequence of steps involved in such a transformation:

Forming a man from the dust of the ground involves causing the prime matter which had the substantial form of dust to take on instead the substantial form of a man. I’m not sure what “sequence of steps” you have in mind. There’s no sequence involved (nor any super-engineering — God is above such trivia). It’s just God “saying,” as it were: “Dust, become a man.” And boom, you’ve got your man.

(For the New Atheist types out there, no, this isn’t “magic.” Rather, it’s something perfectly rationally intelligible in itself and at least partially intelligible to our finite minds once we do some metaphysics. It’s just something that only that in which essence and existence are identical, that which is pure actuality, etc. is capable of, and we aren’t. We have to work through other pre-existing material substances and thus have to do engineering and the like in order to make things. God, who is immaterial, the source of all causal power, etc. doesn’t need to do that and indeed cannot intelligibly be said to do it.)

Professor Feser is not alone in envisaging God’s creative acts in this manner. Thomist scholar Christopher Martin is of the same view. Feser quotes a long passage from Martin in his post, Thomism versus the Design argument (2010), from which I shall reproduce the following excerpt:

The Being whose existence is revealed to us by the argument from design is not God but the Great Architect of the Deists and Freemasons, an impostor disguised as God, a stern, kindly, and immensely clever old English gentleman, equipped with apron, trowel, square and compasses…

The Great Architect is not God because he is just someone like us but a lot older, cleverer and more skilful. He decides what he wants to do and therefore sets about doing the things he needs to do to achieve it. God is not like that… [T]here is nothing that God is up to, nothing he needs to get done, nothing he needs to do to get things done… Acorns for the sake of oak trees, to repeat an example of Geach’s, are definitely something that God wants, since that is the way things are. But it is not that God has any special desire for oak trees (as the Great Architect might), and for that reason finds himself obliged to fiddle about with acorns. If God wants oak-trees, he can have them, zap! You want oak trees, you got ’em. “Let there be oak trees”, by inference, is one of the things said on the third day of creation, and oak trees are made. There is no suggestion that acorns have to come first: indeed, the suggestion is quite the other way around. To “which came first, the acorn or the oak?” it looks as if the answer is quite definitely “the oak”. In any case, what’s so special about oak trees that God should have to fiddle around with acorns to make them? God is mysterious: the whole objection to the great architect is that we know him all too well, since he is one of us. Whatever God is, God is not one of us: a sobering thought for those who use “one of us” as their highest term of approbation.

Professor Christopher Martin’s slighting references to the Great Architect display his lack of familiarity with history. I have already shown, in my previous post, that the reference to God as the “Great Architect” goes back not to the 18th century Freemasons but to John Calvin in the 16th century, and that artistic depictions of God as an Architect go back to the Middle Ages.

Moreover, if Professor Martin believes that proponents of the Design Argument think God needs to make acorns in order to make oaks, then I can only say that he doesn’t know much about the Intelligent Design movement. I don’t know of any Intelligent Design proponent who holds such a view.

What I would maintain, as an ID advocate (and I’m speaking for no-one but myself here), is that if God wishes to make an oak, He needs to specify, down to the last detail, the genetic information He wishes that oak to contain in its cells. If He didn’t do that, then the thing He made wouldn’t be an oak at all. Indeed, it wouldn’t be alive at all. It wouldn’t even be an entity, but only a virtual imitation at best.

Similarly, I maintain that Feser is mistaken in his account of how God could make a man from dust. I hold that it is metaphysically impossible to make a man from dust without specifying, at the atomic level, what should go where (and, I might add, doing quite a lot of nuclear transmutation as well). The reason has nothing to do with any limitations on God’s power; rather, it has to do with the very nature of things.

In a nutshell: the top-level of an entity does not, and cannot, determine all of the details at the bottom. If God tried to make men from the top down, without specifying their constituent atomic particles, then they wouldn’t be men at all. They’d be no more real than the things in the movie, “The Matrix.” Real entities – be they people, animals, plants or minerals – have to be fully specified at the bottom level as well as the top. Otherwise, they’re not entities at all.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The problem of under-determination: Why I think Feser’s account of Divine acts of creation robs things of their “thinghood”

|

|

Left: Daniel Radcliffe, the actor who played the part of Harry Potter in the Harry Potter movie series. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Right: The floor plan of a typical house. Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Nobody knows exactly what the floor plan of Harry Potter’s house looks like, although that has not stopped some fans from making very ingenious guesses (see here and here). That’s because Harry Potter’s house, being a fictional object, has not been completely specified at all levels of description by its author, J.K.Rowling.

To illustrate why real entities have to be fully specified at the bottom level as well as the top, consider the fictional character, Harry Potter. In the story, Harry Potter lives at Number Four, Privet Drive, the home of his Aunt Petunia, Uncle Vernon, and their son Dudley. Now ask yourself this: what color is the roof of Harry Potter’s house? Of course, you don’t know. That’s because the book’s author, Joanne Kathleen Rowling, didn’t tell you. And although she is famous for writing detailed back stories for her books, I doubt whether even she has ever asked herself this simple question. In the story, the color of the roof remains unspecified, and the reader is free to imagine it to be any color that he or she pleases.

That’s fine in a work of fiction, but real roofs have to have a specific color. No roof in the real world has ever had an undetermined color. Even if it was never painted, it always had a color of some sort – namely, the natural color of the roofing material. Real entities need to be specified at the bottom level; otherwise they are not real at all.

Let us suppose, now, that God commanded a piece of dust to become a man, as Professor Feser supposes he did. On behalf of the dust, I would like to reply: “What kind of man would you like me to become, Lord? A tall one or a short one? Brown eyes or blue? A Will Smith lookalike or a Tom Cruise replica? Blood type A, B, AB or O? Oh, and what about the micro-level properties of the man you want me to be? Exactly how many cells should this individual have? What sequence of bases should he have in his DNA? I’m afraid I can do nothing, Lord, unless you tell me exactly what you want.” I won’t belabor the point here: the difficulty should be obvious. The problem with merely telling the dust to become a man is that it under-specifies the effect – or in philosophical jargon, under-determines it. And since dust is unable to make a choice between alternatives – even a random one – then nothing at all will get done, if God commands dust to simply become a man. To get a real man, every single detail in the man’s anatomy has to be specified, right down to the atomic level.

Now we can see why the psalmist wrote: “For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb” (Psalm 139:13).

So contrary to what Feser wrote, I would maintain that God does have to do super-engineering, if He designs an organism. This point has obvious religious implications: for instance, if you happen to believe in the virginal conception of Jesus (as many Christians do) then you will have to grapple with what biologist and Intelligent Design proponent Stephen Jones calls “the mechanics of the Incarnation” (see here for a very interesting blog by Jones on this topic). In short: there’s just no getting around the mechanics of design, even if you’re a Deity. The reason is simple: in the real world, things are specified at all levels, including the bottom level.

Thus my answer to Descartes’ skeptical question, “How can I know whether the world around me is real?” would be: “Try taking it apart. Look at the next layer down, and the layer below that. If you come across a layer whose properties are unspecified, then your world is a fake one.” (Someone will probably ask me about quantum indeterminacy at this point. Here’s my answer: at least there’s determinacy when we make a measurement, so that’s OK. What would be troubling would be making a measurement and getting no result.)

A clarification: Intelligent Design does not claim that information is added to things extraneously; rather, it constitutes things

|

A yellow-bellied sea-snake. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Professor Feser argues, correctly, that the biological information that characterizes a snake is inseparable from its substantial form – i.e. that by virtue of which it is a snake, and not some other kind of animal. Feser might be pleasantly surprised to learn that many Intelligent Design proponents would entirely agree with him on this point.

In a recent blog post entitled, Reply to Torley and Cudworth, Feser criticizes the notion, which he imputes to Intelligent Design proponents, that information can be “poured into” pre-existing things:

A natural object is not a collection of otherwise meaningless or information-free parts to which information, function, teleology or final cause has to be “imparted,” and making a natural object is not a kind of two-stage process which consists first of creating an otherwise meaningless but free-standing material structure and then “introducing” some information or functional properties into it. In the case of a snake or a strand of DNA, for example, there is for A-T simply no such thing as a natural substance which somehow has all the material and behavioral properties of a snake or a strand of DNA and yet still lacks the “information content” or teleological features typical of snakes or DNA. And so, when God makes a snake or a strand of DNA, He doesn’t first make an otherwise “information-free” or teleology-free material structure and then “impart” some information or final causality to it, as if carrying out the second stage in a two-stage process. Such a way of thinking of “design” is possible only against the background of a modern conception of matter which has extruded from it the notions of substantial form and immanent teleology. In short, it is possible only given a rejection of the Aristotelian conception of nature. For on an Aristotelian conception, to be a natural substance at all in the first place is necessarily to have a substantial form and immanent teleology – and therefore, necessarily, already to embody “information.”

Professor Feser will be delighted to learn that I, like other Intelligent Design proponents, completely agree with him on this point. We agree that the biological information that characterizes a living thing is not accidental to it; rather, it is part of its very essence.

Thus I would agree with Feser that if God were to make a man from dust, it would have to be via a single-stage process. It would be absurd to claim that something might have all the material properties of a man (or a snake, to use Feser’s illustration), and yet still not be a man (or a snake). Feser is perfectly correct in saying that for something to have the substantial form of a man (or a snake), it must already embody the “information” that characterizes it as such.

Where I differ from Feser is that he appears to believe that all of the biological information in Adam’s body – on both the micro-level and the macro-level – is an automatic consequence of his having a human form. God says, “Dust, become a man”, and that’s it. Adam has the body he needs. I maintain, on the contrary, that while Adam’s having a human substantial form (or soul) certainly entails that he will have the requisite biological information in his body, it does not fully specify which biological information he has: physical attributes such as height and hair color are left undetermined. Human beings, after all, come in all shapes and sizes. To make Adam have this biological information in his body, God needs to specify the sequence of Adam’s genome (among other things), at the same time as he commands dust to acquire a human form.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

What’s real? What’s not?

I’d now like to address the fundamental question: what does it mean for something to be real?

I would suggest that an entity is real if and only if:

(i) its properties are fully specified – or more accurately, a measurement of any property (or attribute) of that entity always yields a specific value, at any given moment of its existence;

(ii) its relationships are fully specified – or more accurately, a measurement of its relationship to any other given entity always yields a specific value, at any given moment of its existence;

(iii) it is individualized – i.e. it is distinguishable as an individual from other entities of the same kind, during at least some moments of its existence;

(iv) it is concrete, in the sense that measurements of its location in space and/or time yield definite values.

Note on conditions (i) and (ii):

By “fully specified”, I do not necessarily mean “specified by God”. (Entities with libertarian free will are to some degree self-specifying.) By “fully specified”, I simply mean that a measurement of any attribute of that entity always yields a definite value. It may not be possible to measure all of the entity’s properties at the same time, however. (For instance, the Uncertainty Principle tells us that we cannot measure an electron’s position and momentum simultaneously.)

Note on condition (iii):

Two entities may be indistinguishable from each other at some points in time (e.g. two bosons, which can both be present at the same place at the same time). However, I would argue that it makes no sense to speak of two entities which are indistinguishable from each other at all points in time.

Note on condition (iv):

When an entity’s location in space and time is not being measured, it need not have a definite value.

I have argued above that entities as defined by Professor Feser are under-specified, and hence fail to meet conditions (i) and (ii): according to Feser, God can make a man simply by commanding some dust to become a man, without specifying the man’s properties or relationships to other entities.

Another disagreement between Professor Feser and myself is that even if Feser were to accept conditions (i) to (iv), he would definitely want to add a fifth condition to the list above:

(v) the entity’s essence has been endowed with existence.

I think the fifth condition is redundant.

The concept of a phoenix is often cited as an example of something which is not real. However, as it fails all four criteria, I think it is a rather poor example. Someone might ask: “What if God were to mentally envisage a particular phoenix, and completely specify its properties in His mind? Would that make it real?” I would say no, as its relationship with other entities would not be fully specified. But what if these relationships were fully specified in the mind of God? In other words, what if God were to make up a story of that phoenix’s complete life history, and fill in the story with other individuals that were specified to the same level of detail? What if, in addition to that, the entities were clearly distinguishable from each other, and had definite locations in space and time, in the story envisaged by God? Then I would say: that would be enough to make them real.

The “author” metaphor for creation is a very important one, subject to the proviso that the characters in question have free will.

What I’m proposing here is that nothing can even conceivably exist unless it is either a mind or the product of a mind. As John Macmurray pointed out in his books, The Self as Agent and Persons in Relation, even the language we use to describe the behavior of matter (e.g. “attraction”) is inescapably mentalistic. Thus the notion of a mind-independent reality makes no sense. God, who is the Uncaused and Unbounded Intelligent Being, exists at the highest level of reality (call it Level 2). The world and all its creatures (including us) are ideas of God: to be precise, creatures are entities in an interactive novel composed by God. These entities exist on Level 1. Their natures and causal relations are fully specified, and they are also suitably individualized in space-time. However, although their natures are fully specified, their actions are not: the intelligent agents in this interactive novel are free to defy their Maker. Thus in the novel of human history, the details of the plot have not been written by God. We write them, whenever we make choices. As author of the novel, however, God has control over the beginning (i.e. the creation of the world) and also the broad outlines of the ending: in the end, good has to triumph over evil, virtue has to be rewarded, vice has to be punished, and the New Heaven and the New Earth have to be established. The rest of this interactive novel is largely up to us.

Finally, the incompletely specified Pickwickian characters in the stories that human beings write (e.g. Harry Potter, whose house isn’t fully specified in J. K. Rowling’s novels) exist on Level 0. The relation of human authors to their characters is not quite the same as God’s relation to us. While we can write stories whose characters interact with each other and even (if we wish) with their author, our characters lack the autonomy of will (big-L Libertarian freedom) that human beings possess in their relation to God, their Maker. Our characters cannot defy us. They are not real, because they are incompletely specified.

The attraction of this picture, as I see it, is that it dispels a conundrum surrounding creation ex nihilo. Let’s try a humorous experiment: imagine a particular (and as-yet non-existent) entity – say, a flawless 40-carat blue diamond sitting on your desk – and try to wish it into existence. Close your eyes, and think hard. Concentrate! Now open your eyes. Did you succeed? No. But here’s the funny thing: God made you and me and everything else simply by wishing it into existence: “Let there be light.”

So my question is: if we can’t wish things into existence, how come God can? And my very simple answer is that we can wish things into existence, but only in novels of our own creation, on Level 0. The world, which is on Level 1, is God’s novel; the things in our world are products of His mind, not ours. (Of course, entities which are agents, such as ourselves, are also endowed with libertarian free will.) I, on the other hand, can only create (imperfectly specified) things within the stories I compose; whereas God creates fully specified things within His Big Story: the cosmos.

I’d like to close with a quote from St. Augustine (City of God Book V, chapter 11): “Not only heaven and earth, not only man and angel, even the bowels of the lowest animal, even the wing of the bird, the flower of the plant, the leaf of the tree, hath God endowed with every fitting detail of their nature.”