|

|

Can you spot the common theme in these historic statements?

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” – Excerpt from the American Declaration of Independence, which was ratified on July 4, 1776.

“Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.” – Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), article 1. The Declaration was approved by the National Constituent Assembly of France, on August 26, 1789.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” – Excerpt from President Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered on November 19, 1863.

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” – Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), article 1. The Declaration was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948 at the Palais de Chaillot, Paris.

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.‘”- Excerpt from the famous ‘I Have a Dream’ speech by Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered on 28 August 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington D.C.

(Emphases mine – VJT.)

Belief in human equality is a vital part of our democratic heritage. Take this belief away, and the moral foundations of Western civilization immediately collapse, like a house of cards.

Atheists divided

Sad to say, many (perhaps most) of the world’s 25 most influential living atheists don’t seem to share this belief. Specifically, many of these atheists don’t believe that newborn babies have the same moral worth as human adults.

However, there are some notable exceptions. Quite a few of the world’s most influential atheists still firmly believe that newborn babies are just as important as adults, and for that, I applaud them.

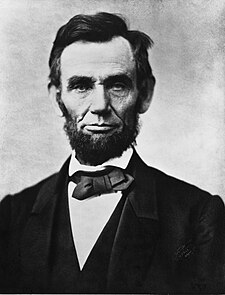

The question of whether newborn babies have the same moral worth as human adults is a fundamental one. Putting it another way: is killing a newborn baby just as bad as killing an adult? If the world’s top atheists cannot even agree on this issue, then I think it is fair to regard them as a house divided. And a house divided against itself cannot stand, as Abraham Lincoln remarked (quoting Matthew 12:25) in a famous speech he delivered on June 16, 1858.

The inability of the world’s leading atheists to agree on such a simple moral question is big news. I think readers of this blog are entitled to hear about that.

Evidence, please?

I hear some of my readers asking, “So where’s your evidence that the world’s top atheists disagree on this issue?” I’m very happy to oblige. Here goes.

In a recent post, I invited the world’s 25 most influential living atheists to respond to a short quiz on the moral status of newborn babies. To make sure that they knew about the quiz, I contacted as many of them as I could (i.e. nearly all of them) by email. Three atheists (Professor Peter Atkins, Dr. Richard Carrier and Dr. Michael Shermer) were kind enough to respond to my quiz. Another (James Randi) declined to respond, on the grounds that his answers would be too lengthy, but at least he was polite enough to answer my email. Six more atheists (Professor P. Z. Myers, Professor Peter Singer, Professor Steven Pinker – see also here and here, – Professor Daniel Dennett, Professor Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens) had already made their views plain, in a public forum, so I was able to identify how they would have responded. Unfortunately, I was not able to ascertain the views of Sam Harris, Stephen Hawking, Steven Weinberg, Paul Kurtz, Lawrence Krauss, Edward O. Wilson, Jennifer Michael Hecht, John Brockman, Philip Pullman, Barbara Forrest, David Sloan Wilson, Ray Kurzweil, William B. (“Will”) Provine, Kai Nielsen and Susan Blackmore. I was pleased, however, that I had managed to find out how nine of the 25 most influential living atheists viewed the moral status of newborn babies.

There were five questions in my short quiz. One regular reader and commenter on Uncommon Descent, markf, remarked on his blog that “the response to the last question is the only interesting one.” He was right, and I’m going to focus on this question in this post. The last question on my quiz was:

Do you believe that killing a newborn baby is just as wrong as killing an adult?

I soon discovered that the world’s 25 most influential living atheists are divided on this question. To his credit, Dr. Michael Shermer answered with a straight “Yes.” Professor Peter Atkins answered with a qualified “Yes,” adding that if the baby were irrevocably damaged in some way, he would modify his response. And on the basis of statements he has made on Youtube, I was able to ascertain that Christopher Hitchens would answer my question with an emphatic “Yes.”

Dr. Richard Carrier, on the other hand, answered “No,” and carefully explained his reasons. Although he believes newborn babies are persons with a right to life, he also believes that the moral worth of an adult is generally greater than that of a newborn baby; hence killing a baby isn’t as bad as killing an adult. Carrier doesn’t believe that all human beings are equal; rather, he believes that human beings occupy different points on a scale of moral worth. Three other atheists who did not respond (Professor P. Z. Myers (see here for a recent post of his, here for one reader’s comment on the post and here for P. Z. Myers’ reply), Professor Peter Singer, and Professor Daniel Dennett) have already made it clear in their published writings that they don’t even regard newborn babies as persons, let alone as individuals whose moral worth is equal to that of adults. Obviously, these atheists would answer “No” to my question. Professor Steve Pinker has published an article (“Why they kill their newborns”, The New York Yimes, November 2, 1997) in which he appears to suggest that he doesn’t regard newborn babies as persons, although he opposes the legalization of infanticide. However, he is quite up-front about one thing: he doesn’t think that killing a newborn baby is a crime of the same gravity of killing an adult. (See here, here and here for a discussion.) Finally, I was able to ascertain from Professor Richard Dawkins’ book, The God Delusion (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2006), that he regards individuals with highly developed nervous systems as having a greater moral worth than individuals with poorly developed nervous systems, because the former are capable of much greater suffering than the latter. As Dawkins puts it in his discussion of abortion:

A consequentialist or utilitarian is likely to approach the abortion question in a very different way, by trying to weigh up suffering. Does the embryo suffer? (Presumably not if it is aborted before it has a nervous system; and even if it is old enough to have a nervous system it surely suffers less than, say, an adult cow in a slaughterhouse.) Does the pregnant woman, or her family, suffer if she does not have an abortion? Very possibly so; and, in any case, given that the embryo lacks a nervous system, shouldn’t the mother’s well-developed nervous system have the choice?

But since a newborn baby’s nervous system is also far less developed than an adult’s, it follows that on Professor Dawkins’ view, killing a newborn baby is not as bad as killing an adult.

That makes three of the world’s 25 most influential atheists who believe that killing a newborn baby is just as wrong as killing an adult, and six of these atheists who don’t think it is. Unfortunately, I was unable to ascertain the opinions of the remaining sixteen atheists, on this vital ethical question. However, the big split in opinion on such a basic moral issue highlights the fact that on ethical matters, the world’s leading atheists are a house divided.

This prompts me to ask: if the world’s top atheists cannot even agree on this issue, how much confidence can we have in their repeated assertion that “naturalistic ethics” can deliver “goodness without God”?

Blowing smoke

Now that I’ve exposed the ethical disunity of the world’s leading atheists, I expect one of them will respond with a withering attack on my allegedly “simplistic” approach to ethics. We’ll doubtless be subjected to a long lecture about the hardships faced by our ancestors, about how difficult it was for mothers to simultaneously nurse two children in pre-industrial societies, and about how these mothers often had to make painful choices about which child to feed and which to let die. (All perfectly true, but completely irrelevant to the ethical point at issue, which is: do babies matter just as much as the rest of us do?) The “history lecture” will then be followed by a self-righteous tirade against “absolutist” ethics, with its high-falutin’ talk of “persons,” “rights,” “duties” and “moral worth.” Morality, we will be told, is always context-dependent, and there are no black-and-white answers to moral questions. (Now that’s a self-refuting assertion if ever I heard one.)

To my readers, I would like to say: don’t be fooled. All of this is nothing but an exercise in blowing smoke. It reflects the desperation of the world’s leading atheists to cover up the embarrassing fact that they cannot even agree on a simple ethical question: do newborn babies matter as much as the rest of us? Or putting it another way: is killing a newborn baby just as wrong as killing any other member of the community?

Now, I realize that there are some people who would reject the foregoing questions as meaningless. These people tend to have an instinctive distrust of abstract ethical reasoning, and they will stoutly maintain that moral questions can only be answered in relation to a particular time, place and circumstance. So here’s my answer to them. You want a concrete moral situation? Fine. I’ll give you one.

A tale of two killers

A man (let’s call him Smith) with an automatic weapon walks into a hospital maternity ward and kills the nurse on duty, before being wrestled to the ground by two alert, courageous bystanders. At the same time, in a nearby town, another man (let’s call him Jones) with an identical automatic weapon walks into a hospital maternity ward and kills a newborn baby, before being wrestled to the ground. Both men are put on trial, and both of them are declared sane and capable of distinguishing right from wrong, at the time of the killings. Should both receive the same punishment?

We know how nine of the 25 most influential living atheists would answer this question. Three would say yes, and six would say no. Six of these atheists would regard the nurse as having a greater moral worth than the newborn baby; hence they would say that the gravity of Smith’s offense is greater than that of Jones. Only three atheists (out of the nine whose views I was able to identify) would correctly answer that Smith and Jones should be punished in the same way.

Six of the world’s most influential atheists would give Jones a lighter punishment than Smith. I have to say that I find that scandalous. I will continue to call these six atheists out on this one, because their position is morally odious.

A short note on the practice of infanticide in human history

Let me add that I am quite aware of the reasons why infanticide was practiced in pre-industrial societies, and why it continues to be practiced in some societies today. (Readers might like to have a look at this article, and also here and here.) I have no wish to pass judgment on mothers in times past, who were faced with conflicting obligations about which child they should feed, or mothers who were unable to take proper care of their babies without jeopardizing the lives of other people in their community. But the fact that these mothers had to make difficult choices about their babies, in extreme situations, doesn’t imply that they believed that the babies they killed were any less important, morally speaking, than the adults in their community. All it shows is that these adults were not able to take care of the newborn babies, owing to the extreme poverty of their community. The same goes for hunter-gatherer communities that were sometimes forced to abandon elderly people whom they were no longer able to take care of, because they were unable to keep up with the rest of the tribe. Nobody in these communities attempted to rationalize the practice by saying that old folk are “less important” than young people; the community was simply unable to take care of them, that’s all.

Other cases of infanticide simply reflect long-standing cultural prejudices against women. I have no sympathy with communities that engage in the barbaric practice of female infanticide, which remains widespread in India and China (see here and here). Why? Because I know of other cultures, which eventually managed to eradicate this vile practice: first, the Jews in ancient Israel (Leviticus 18:21; Deuteronomy 18:10-13; Psalm 106:35-40), and later on, the Christians in Europe (see here, here and here) and the Muslims in the Arab world (see here). If they could do it, then I have to ask: why can’t India and China? So yes, I do condemn the people who perpetuate the practice of child murder in these countries: furious fathers who were hoping for a son, elderly matriarchs who pressure young mothers into killing their baby girls because they were once told by their husbands to do the same thing, and yes, also the weak, acquiescing mothers who kill their baby girls because they’re afraid of being shunned, humiliated or beaten up. The acquiescence of these mothers is understandable, but it’s still morally wrong. There are some injustices you have to stand up to, because if you don’t, then who will?

A woman’s fear of having an illegitimate birth exposed is another common reason for the occurrence of infanticide in history. Again, while we can certainly understand the action of a mother who kills her newborn child in such circumstances, that does not make it right. Someone has to eventually stand up and fight an unjust social system which victimizes illegitimate mothers, while letting the fathers get off scot-free.

Finally, the silliest historical reason for the practice of infanticide was a religious one: some ancient societies condoned and even mandated child sacrifice as a way of placating the gods. And now ask yourself this: if you had lived in those times, and you wanted to uproot this barbarous practice, do you think that you could have done so if you were also on the record as publicly affirming, as many modern atheists do, that babies don’t matter as much as adults? Would you not stand a much better chance if you were armed with a prophetic warning from an angry God, who claimed to be the one true God, and who (i) asserted that children and adults alike were made in His image and likeness, (ii) declared the practice of child sacrifice to be a detestable abomination, and (iii) commanded the destruction of altars dedicated to the false gods whose priests demanded this sacrifice?

Religion has been responsible for many abuses in human history, but atheism is a totally ineffective way to combat these abuses. Only a good religion can displace the harmful practices of a bad religion.

In my next post, I shall argue that key concepts invoked by Intelligent Design can help us to understand precisely why all human beings – from embryos to Einstein – are of equal moral worth.