|

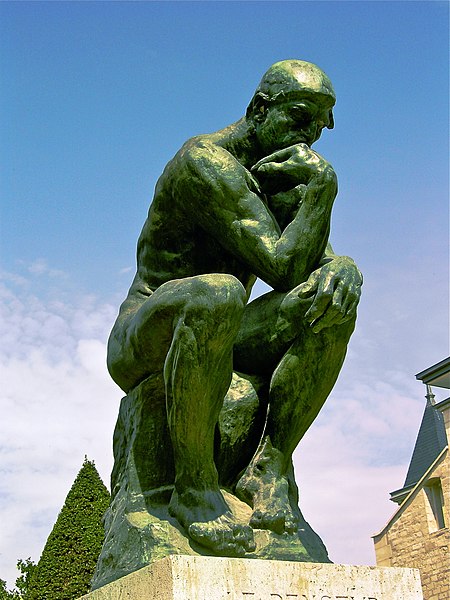

My intention in writing this post is to clear Rev. William Paley of two charges that have been leveled against him: first, that the God he argues for is different in certain vital respects from the God of classical theism, and second, that Paley’s design argument leads us to a false God: not a Creator, but a mere cosmic architect, who is a powerful but finite being, differing from us merely in degree. Both of these charges have been hurled against Paley by Associate Professor Edward Feser (who surely needs no introduction here) and by Professor Christopher F. J. Martin, of the University of St. Thomas, Department of Philosophy and Center for Thomistic Studies, in Houston, Texas. These are grave charges, and if true, they would imply that no-one who believes in the transcendent God of the Bible (as many people do) can support Intelligent Design – for if Paley’s God is a false one, surely the same could be said of the Intelligent Designer. (As it is an empirical research program, ID theory makes no pronouncements regarding the identity of the Designer, but it would be fair to say that most ID supporters believe that this Designer is God.) If Feser and Martin are right, then many Intelligent Design advocates worship a false God: Zeus (pictured above), perhaps, but not YHWH.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Feser’s and Martin’s charges against Paley and the Intelligent Design movement

In his blog post, Thomism versus the design argument (March 15, 2011), Professor Edward Feser makes the extraordinary claim that both Paley and Intelligent Design theory take us away from classical theism and towards paganism:

My objection to Paley and to ID theory has consistently been that, given:

(a) their eschewal, even if only “for the sake of argument,” of immanent formal and final causes and thus of the classical metaphysical apparatus associated with them (such as the act/potency distinction), and

(b) their univocal application of predicates both to God and to human designers (as opposed to “analogous” predication, in the Thomistic sense of the term),

these approaches lock us within the natural order and cannot in principle get us beyond it. In particular, they cannot in principle get us to a “designer” that is anything but one creature among others, even if a grand and remote one. In short, they get us to paganism, and thus away from classical theism.

Strong words, indeed! And Feser is not alone. Professor Christopher Martin, author of Thomas Aquinas: God and Explanations, whom Professor Feser cited favorably in his online posts, The trouble with William Paley (November 4, 2009) and Thomism versus the design argument (March 15, 2011). Here is what Christopher Martin has to say about Paley’s Design Argument in his chapter, The Fifth Way:

The argument from design had its heyday between the time of Newton and the time of Darwin, say, a time in which most people apparently came to see the world as a minutely designed piece of craftsmanship, like a clock. It is no coincidence that the most famous presentation of the argument from design actually compares the world to a clock: it is known by the name of Paley’s watch…

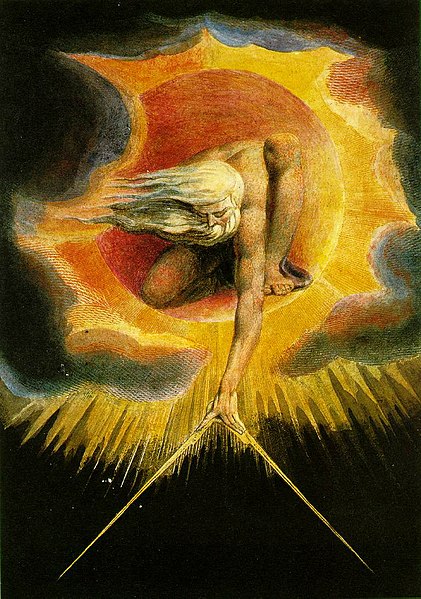

The Being whose existence is revealed to us by the argument from design is not God but the Great Architect of the Deists and Freemasons, an impostor disguised as God, a stern, kindly, and immensely clever old English gentleman, equipped with apron, trowel, square and compasses. Blake has a famous picture of this figure to be seen on the walls of a thousand student bedrooms during the nineteen-seventies: the strong wind which is apparently blowing in the picture has blown away the apron, trowel and set-square but left him his beard and compasses. Ironies of history have meant that this picture of Blake’s is often taken to be a picture of God the Creator, while in fact Blake drew it as a picture of Urizen, a being who shares some of the attributes of the Great Architect and some of those of Satan.

The Great Architect is not God because he is just someone like us but a lot older, cleverer and more skilful. He decides what he wants to do and therefore sets about doing the things he needs to do to achieve it. God is not like that.

As Hobbes memorably said, “God hath no ends”: there is nothing that God is up to, nothing he needs to get done, nothing he needs to do to get things done…. God is mysterious: the whole objection to the great architect is that we know him all too well, since he is one of us. Whatever God is, God is not one of us: a sobering thought for those who use “one of us” as their highest term of approbation.

(Christopher F. J. Martin, Thomas Aquinas: God and Explanations, Edinburgh University Press, 1998, pp. 180-82.)

So if Professor Martin is right, those who worship Paley’s false God are worshiping a being who has some of the features of Satan! I have to say that this is really over the top. Not only that, but it’s manifestly inaccurate, as I’ll demonstrate below.

Before I go on, however, I’d like to address a specific accusation that Professor Feser makes against Paley and the Intelligent Design movement: that they are guilty of “univocal application of predicates both to God and to human designers (as opposed to ‘analogous’ predication, in the Thomistic sense of the term).” In other words, Feser thinks that both Paley and modern Intelligent Design proponents are guilty of anthropomorphism: in the words of J.B. Phillips, our God is too small.

According to Feser, that Paley’s Design argument implicitly assumes that the word “intelligent” has the same meaning when applied to the Intelligent Designer and human designers – otherwise design inferences from patterns in Nature would be invalid. But if this Intelligent Designer is God, then what the Design argument is really saying is that the word “intelligent” means the same thing when applied to God and to ourselves. That’s univocal predication, and Feser (who is a Thomist) will have none of it. Feser insists that the differences between God (Who is Pure Being) and His creatures are so vast that no term that we apply to human beings (e.g. the term “intelligent”) can possibly have the same meaning when applied to God. At best, it can only have a meaning that is similar in some respects, but very different in others. God’s intelligence is in some ways similar to our own, but in others it is radically different. Paley’s design argument, which claims that the existence of an Intelligent Designer is knowable through a scientific study of Nature, offers us a pint-sized deity: one who differs from us only in degree, and not in kind. For Feser, that’s blasphemy.

In response, let me begin by noting that the Thomistic doctrine of analogy (see here for a short, simple explanation) isn’t defined doctrine, even for Catholics. Scotists (who follow the philosophical teachings of Blessed John Duns Scotus) famously reject the Thomist doctrine of analogy. The medieval philosopher John Duns Scotus (1265-1308) held that since intelligence and goodness were pure perfections, not limited by their very nature to a finite mode of realization, they could be predicated univocally (i.e. in the same sense) of God and human beings. To be sure, God’s manner of knowing and loving is altogether different from ours: it belongs to God’s very essence to know and love perfectly, whereas we can only know and love by participating in God’s knowledge and love. Also, God’s knowledge and goodness are essentially infinite, while our knowledge and goodness are finite. Indeed, God is Pure Knowledge and Love, whereas we merely possess these attributes. However, according to Scotus, what it means for God to know and love is exactly the same as what it means for human beings to know and love. This is because the verb “know,” when applied to an intelligent being, is not meant to refer to the manner of his/her knowledge or for that matter, the degree of knowledge he/she possesses; rather, it simply refers to the fact that he/she stands in the right relation towards that which is known – a relation we call “understanding.”

And I should add that the Catholic Church has never condemned Duns Scotus’ views. As The Catholic Encyclopedia notes in its article on Scotism, there have even been bishops, cardinals, popes, and saints who were followers of Duns Scotus’ philosophy. So Feser’s theological charge against Paley and the Intelligent Design movement is starting to look very shaky. If he can’t even make his charge stick for the Catholic Church, how much less so for other religious groups which profess to believe in the God of the Bible?

The second point I’d like to make in reply to Feser is that there’s nothing anthropomorphic about the way in which the ID movement defines the word “intelligent.” Here, for instance, is how Professors William Dembski and Jonathan Wells define the terms “intelligent design,” “intelligence” and “design” in their book, The Design of Life (2008, Foundation for Thought and Ethics, Dallas, page 3):

Intelligent Design. The study of patterns in nature that are best explained as the product of intelligence.

Intelligence. Any cause, agent, or process that achieves and end or goal by employing suitable means or instruments.

Design. An event, object, or structure that an intelligence brought about by matching means to ends.

On page 315, Dembski and Wells define intelligence in more detail, as “A type of cause, process or principle that is able to find, select, adapt, and implement the means needed to effectively bring about ends (or achieve goals or realize purposes). Because intelligence is about matching means to ends, it is inherently teleological.”

In calling the Designer intelligent, then, all we are saying is that the Designer is capable of directing means towards their ends. Nothing more than that. Professor Feser is a Thomist, so he will doubtless recall that Aquinas said the same thing, in his Summa Contra Gentiles, Book I, chapter 44, paragraph 7:

Since, then, things do not set for themselves an end, because they have no notion of what an end is, the end must be set for them by another, who is the author of nature. He it is who gives being to all things and is through Himself the necessary being. We call Him God, as is clear from what we have said. But God could not set an end for nature unless He had understanding. God is, therefore, intelligent.

I would like to ask Professor Feser: is this anthropomorphism? If not, then why do you accuse Rev. William Paley and Intelligent Design proponents who believe in God of being anthropomorphic for saying the same thing?

I shall rebut the charges that Professor Christopher Martin makes against Paley and the Intelligent Design movement later in this essay. But first of all, I’d like to examine what Rev. William Paley actually wrote about God in his Natural Theology.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

What did Paley actually say about God, in his Natural Theology?

The first paragraph of the Shema, as written on a Torah scroll: “Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is one.” Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The unity of God is one of several attributes that classical theists ascribe to Him, along with such attributes as transcendence, aseity (being uncaused), omniscience, omnipotence, omnibenevolence, simplicity, timelessness, immutability, and impassibility. William Paley explicitly ascribed most of these attributes to God, and it can be argued that he would have willingly ascribed all of them to God, in at least a broad sense.

|

In his Natural Theology, Paley argued that the Designer of Nature must be:

(a) transcendent, because contrivances are found at all levels throughout Nature, so their Author must lie beyond Nature; In all these respects, Paley’s God is identical with the God of classical theism. On two points, however, Paley differs from most classical theists. First, Paley equates the necessity of God with the possibility of our demonstrating His existence, whereas for classical theists, God’s necessity is usually grounded in the notion that God is Pure Existence, and hence incapable of non-existence. However, since Paley argued that God is outside time, it would follow for him also that God is incapable of ceasing to exist. Second, Paley appears to believe that God is capable of perceiving the world in some way. Even if this perception occurs timelessly in the mind of God, it would still mean that He is passible, or capable of being affected by the world. Classical theism, however, traditionally holds that God is impassible, in the strict sense: the world has no power to causally influence God, as He is in no way affected by the actions of His creatures. However, neither the necessity nor the impassibility of God (in this strict sense) forms part of the defined teachings of Judaism, Christianity or Islam. None of these religions teach that God is Pure Existence. Nor do they teach that God is impassible, in the strict sense of being in no way affected by His creatures; rather, what they teach is that God does not have passions, or bodily feelings. I conclude that Paley falls within the broad tradition of classical theism, albeit of a very pragmatic variety, insofar as he endeavors to explain the Divine attributes in terms of how they affect us, rather than describing them in terms of God’s inner being – a subject about which Paley prefers not to speculate. |

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

What is classical theism?

Finding a generally agreed definition of classical theism is no easy matter. I have decided to use the definition given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, in its article on Concepts of God:

Most theists agree that God is (in Ramanuja’s words) the “supreme self” or person — omniscient, omnipotent, and all good. But classical Christian theists have also ascribed four “metaphysical attributes” to God — simplicity, timelessness, immutability, and impassibility.

Impassibility, in the strict sense of the word, means that nothing affects God; God has no experiences, and the world has no influence over Him:

…[N]othing acts on God or causally affects him. While the world is affected by God, God is not affected by it…

According to the doctrine of impassibility, God is not affected by his creatures. Everything other than God depends upon him for both its existence and qualities. God himself, though, depends upon nothing.

However, Wikipedia also gives another, broader definition of the term:

God does not experience pain or pleasure from the actions of another being.

Defined in this broader sense, the doctrine of impassibility simply means that God does not have passions, or bodily feelings. As we shall see, this broader definition was used in some credal statements.

Do any of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) require a belief in the God of classical theism?

Surprisingly, neither Judaism nor Christianity nor Islam requires its members to believe in the God of classical theism.

What Judaism teaches about the nature of God

The essential tenets of Judaism in relation to God’s nature, as defined in Maimonides’ Thirteen Articles of the Jewish Faith, are that God exists, God is one and unique, God is incorporeal, God is eternal, and God knows the thoughts and deeds of men. Although God is generally agreed to be omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent and eternal, the thirteen articles make no claim that God is infinite. God is also said to be indivisible, from which God’s simplicity might be deduced, but the articles say nothing about God’s timelessness, immutability or impassibility.

What Christianity teaches about the nature of God

If we look at the Christian faith, we find a great diversity of denominations, each with its own credal statements. I shall limit my discussion to the dogmatic pronouncements of the Catholic Church, the Anglican Thirty-nine Articles of Religion, and on the Protestant side, the Westminster Confession of Faith.

(a) What the Catholic Church teaches

The Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 made the following declaration concerning God, in Chapter 1 of its decrees:

428 Firmly we believe and we confess simply that the true God is one alone, eternal, immense, and unchangeable, incomprehensible, omnipotent and ineffable, Father and Son and Holy Spirit: indeed three Persons but one essence, substance, or nature entirely simple.

The ecumenical Council of Florence (1438-1445) made the following declaration concerning God, in session 11:

First, then, the holy Roman church, founded on the words of our Lord and Saviour, firmly believes, professes and preaches one true God, almighty, immutable and eternal, Father, Son and holy Spirit; one in essence, three in persons…

The position of the Catholic Church was reiterated in the following pronouncement by the First Vatican Council (1869-1870):

The Holy Catholic Apostolic Roman Church believes and professes that there is one living and true God, Creator and Lord of heaven and earth, omnipotent, eternal, immense, incomprehensible, infinite in intellect and will and in all perfection Who, being One, singular, absolutely simple and unchangeable spiritual substance, is to be regarded as distinct really and in essence from the world most blessed in and from Himself, and unspeakably elevated above all things that exist, or can be conceived, except Himself. (Session III, April 24, 1870) (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02062e.htm )

If we carefully examine these dogmatic declarations, we find to our surprise that God’s omniscience, omnipresence and omnibenevolence are nowhere explicitly affirmed, although the phrase, “infinite in intellect and will and in all perfection” might reasonably be taken to imply them. Only God’s omnipotence is explicitly affirmed, and its scope is not specified. St. Thomas Aquinas held that God could do anything which was logically possible, but the Catholic Church has never defined this.

The absolute simplicity of God is clearly affirmed, but only insofar as it pertains to the Divine essence. There is no dogmatic declaration by the Catholic Church condemning the notion that in God, there may be a distinction between His substance (or essence) and His accidents; nor is the Eastern Orthodox theological notion that God’s operations are distinct from His essence condemned by any ecumenical council.

Regarding God’s immutability: at the First Vatican Council, God is said to be an “unchangeable spiritual substance.” Nothing is said, however, regarding whether God is capable of changing in other ways, not relating to His substance as such. Nor is there any official dogmatic declaration that God is timeless.

Finally, God’s impassibility (in the strict sense of the term) is nowhere affirmed, either explicitly or implicitly. Even to this day, it is not a defined Catholic doctrine. Some Thomists, including Professor Feser, have claimed that God’s impassibility is a logical consequence of His immutability. In reality, however, all that follows from the doctrine of God’s immutability is that if God is affected by His creatures, He is affected in a timeless manner. It does not follow that He is not affected at all.

The sixth century theologian Boethius is commonly supposed to have held that God knows the past, present and future by a kind of “knowledge of vision”: He timelessly observes all our actions. On Boethius’ account, then, the world is capable of causally influencing God. Indeed, most Catholic laypeople envisage God’s foreknowledge in this fashion. If we define “impassibility” in its strict sense, we would then have to say that Boethius was not a classical theist! However, Boethius is generally regarded as a thinker within the classical theist tradition.

(b) What the Church of England teaches

The first of the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion, promulgated in 1571 with the approval of Queen Elizabeth I, is titled, “Of faith in the Holy Trinity,” and reads as follows:

THERE is but one living and true God, everlasting, without body, parts, or passions; of infinite power, wisdom, and goodness; the maker and preserver of all things both visible and invisible. And in unity of this Godhead there be three Persons, of one substance, power, and eternity; the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

The article thus declares God to be omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent, but does not explicitly mention His omnipresence. God is said to be without parts, making Him simple, but He is nowhere said to be timeless; rather, He is said to be eternal (which may mean either timeless or omnitemporal). Nothing in the article explicitly declares God to be immutable. Finally, the statement that God is without passions could be interpreted as meaning that He is impassible; alternatively, it could simply mean that God has no bodily passions, such as hunger or desire.

As an Anglican archdeacon, Rev. William Paley would have presumably assented to the statements made in this article of religion.

(c) What the Presbyterian Church teaches

Chapter 2 of The Westminster Confession of Faith is titled, Of God, and of the Holy Trinity. The chapter reads as follows:

I. There is but one only, living, and true God, who is infinite in being and perfection, a most pure spirit, invisible, without body, parts, or passions; immutable, immense, eternal, incomprehensible, almighty, most wise, most holy, most free, most absolute; working all things according to the counsel of His own immutable and most righteous will, for His own glory; most loving, gracious, merciful, long-suffering, abundant in goodness and truth, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; the rewarder of them that diligently seek Him; and withal, most just, and terrible in His judgments, hating all sin, and who will by no means clear the guilty.

II. God has all life, glory, goodness, blessedness, in and of Himself; and is alone in and unto Himself all-sufficient, not standing in need of any creatures which He has made, nor deriving any glory from them, but only manifesting His own glory in, by, unto, and upon them. He is the alone fountain of all being, of whom, through whom, and to whom are all things; and has most sovereign dominion over them, to do by them, for them, or upon them whatsoever Himself pleases. In His sight all things are open and manifest, His knowledge is infinite, infallible, and independent upon the creature, so as nothing is to Him contingent, or uncertain. He is most holy in all His counsels, in all His works, and in all His commands. To Him is due from angels and men, and every other creature, whatsoever worship, service, or obedience He is pleased to require of them.

III. In the unity of the Godhead there be three Persons of one substance, power, and eternity: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost. The Father is of none, neither begotten nor proceeding; the Son is eternally begotten of the Father; the Holy Ghost eternally proceeding from the Father and the Son.

The article thus declares God to be almighty and most wise, and declares that He has sovereign dominion over His creatures, as well as infinite knowledge. These statements would seem to imply that God is omnipotent and omniscient. God’s omnibenevolence is nowhere explicitly affirmed, but one might argue that it follows from His being “most holy” and “most loving.” The chapter does not explicitly mention God’s omnipresence, but it does declare that all things take place “in His sight.” God is said to be without parts, making Him simple. Although God is not explicitly said to be timeless, the article explicitly declares God to be immutable, which would imply that God is timeless. Finally, the statement that God is “without passions,” coupled with the statements that “nothing is to Him contingent” and that God is “unto Himself all-sufficient, not standing in need of any creatures which He has made,” seems to imply that God is impassible.

The Westminster Confession of Faith is thus the only Christian credal document I know of which implicitly or explicitly affirms all of the tenets of classical theism.

What Islam teaches about the nature of God

The official teaching of Islam is somewhat vaguer than that of Christianity. While Muslim teaching on the Nature of Allah declares Him to be utterly incomprehensible, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent and incorporeal, as well as both just and merciful, there is nothing, as far as I can tell, requiring Muslims to believe that He is simple, timeless, immutable or impassible.

Let us now examine the question of whether Rev. William Paley himself believed in classical theism.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Did Paley believe in classical theism?

It is fair to assume that Paley, as an Anglican clergyman, would have assented to the first of the Elizabethan Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, which reads as follows:

There is but one living and true God, everlasting, without body, parts, or passions; of infinite power, wisdom, and goodness; the maker and preserver of all things both visible and invisible. And in unity of this Godhead there be three Persons, of one substance, power, and eternity; the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

The article clearly affirms God’s omniscience, omnipotence and omnibenevolence, and describes God as being without parts – or in other words, simple.

Since the article describes God as being both everlasting and eternal (see also the second article, which speaks of “the very and eternal God”), and since the doctrine of God’s timelessness and immutability was generally accepted by Christians of all stripes in Paley’s day, it is reasonable to conclude that Paley would have imputed these attributes to God as well. It is true that there are passages in Paley’s Natural Theology where he speaks of God as existing before His creation, but similar passages can be found in Scripture itself (Proverbs 8:23-26; John 17:24; Ephesians 1:4; 1 Peter 1:20), and Paley elsewhere speaks of God as possessing “a power … to which we are not authorized, by our observation or knowledge, to assign any limits of space or duration” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 444). As a clergyman, Paley must also have been aware of the Scriptural affirmation, “I the Lord do not change” (Malachi 3:6). Regarding these two Divine attributes, then, I think Paley deserves to be given the benefit of the doubt.

Finally, the first of the Elizabethan Thirty-nine articles describes God as being “without passions,” so in this broad sense, Paley would have accepted the doctrine of Divine impassibility, held by classical theists. In his Natural Theology, however, he speaks of God as “a perceiving, intelligent, designing, Being” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 441-442). Since (as we saw above), Paley almost certainly believed that God is unchangeable, he must therefore have held that God is capable of being timelessly made aware of events occurring in this world. This would not require God to change, but it would mean that He was capable of being causally influenced by the world. In the strict sense of the word, then, Paley did not accept the notion of Divine impassibility. If, however, impassibility is defined more broadly as “inability to suffer or experience pain or other bodily feelings,” then Paley would certainly have accepted this definition, as He held that God is a spirit, and a perfect one at that.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Two views of classical theism

|

|

Thomas Williams, in his article on John Dus Scotus (Pictured above right), in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, argues that there are at least two ways of grounding God’s attributes. According to St. Thomas Aquinas (Pictured above left), since God is Pure Existence, His absolute simplicity is what grounds the other Divine attributes; whereas on Scotus’ view, God is Infinite Being, His infinity is what grounds these attributes:

…[T]he concept of “infinite being” has a privileged role in Scotus’s natural theology. As a first approximation, we can say that divine infinity is for Scotus what divine simplicity is for Aquinas. It’s the central divine-attribute generator. But there are some important differences between the role of simplicity in Aquinas and the role of infinity in Scotus. The most important, I think, is that in Aquinas simplicity acts as an ontological spoilsport for theological semantics. Simplicity is in some sense the key thing about God, metaphysically speaking, but it seriously complicates our language about God. God is supposed to be a subsistent simple, but because our language is all derived from creatures, which are all either subsistent but complex or simple but non-subsistent, we don’t have any way to apply our language straightforwardly to God. The divine nature systematically resists being captured in language.

For Scotus, though, infinity is not only what’s ontologically central about God, it’s the key component of our best available concept of God and a guarantor of the success of theological language. That is, our best ontology, far from fighting with our theological semantics, both supports and is supported by our theological semantics. The doctrine of univocity rests in part on the claim that “[t]he difference between God and creatures, at least with regard to God’s possession of the pure perfections, is ultimately one of degree” (Cross [1999], 39). Remember one of Scotus’s arguments for univocity. If we are to follow Anselm in ascribing to God every pure perfection, we have to affirm that we are ascribing to God the very same thing that we ascribe to creatures: God has it infinitely, creatures in a limited way. One could hardly ask for a more harmonious cooperation between ontology (what God is) and semantics (how we can think and talk about him).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Did Paley argue for classical theism, in his Natural Theology?

The question of whether classical theism is properly grounded in God’s absolute simplicity (as Aquinas thought) or God’s infinity (as Scotus maintained) has a significant bearing on whether Rev. William Paley can legitimately be said to have argued for the truth of classical theism in his Natural Theology.

Paley emphatically argued for God’s simplicity in his Natural Theology, in a passage where he contends that the Designer of Nature must be immaterial and could not possibly be composed of material parts. If He contained any contrivances, argues Paley, then He would no longer be self-existent:

Of this however we are certain, that whatever the Deity be, neither the universe, nor any part of it which we see, can be He. The universe itself is merely a collective name: its parts are all which are real; or which are things. Now inert matter is out of the question: and organized substances include marks of contrivance. But whatever includes marks of contrivance, whatever, in its constitution, testifies design, necessarily carries us to something beyond itself, to some other being, to a designer prior to, and out of, itself. No animal, for instance, can have contrived its own limbs and senses; can have been the author to itself of the design with which they were constructed. That supposition involves all the absurdity of self-creation, i. e. of acting without existing. Nothing can be God, which is ordered by a wisdom and a will, which itself is void of; which is indebted for any of its properties to contrivance ab extra. The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see. Which consideration contains the answer to a question that has sometimes been asked, namely, Why, since something or other must have existed from eternity, may not the present universe be that something? The contrivance perceived in it, proves that to be impossible. Nothing contrived, can, in a strict and proper sense, be eternal, forasmuch as the contriver must have existed before the contrivance.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412).

While the foregoing argument by Paley precludes God’s having any material parts, a Thomist might still object that Paley makes no attempt to establish that the Designer has no metaphysical parts. As Professor Edward Feser explains in his online post, Classical theism (30 September, 2010), in classical theism, God’s simplicity is defined in metaphysical terms:

To say that God is simple is to say that He is in no way composed of parts – neither material parts, nor metaphysical parts like form and matter, substance and accidents, or essence and existence.

From a Thomistic perspective, then, Paley’s argument for classical theism appears incomplete.

In reply, I would suggest that Paley does not spell out the argument for God’s absolute simplicity in further detail, precisely because it was so well-known to his contemporaries. In his Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 448), Paley quotes from page 106 of Bishop Wilkins’ Principles of Natural Religion, when arguing that the Designer of Nature must be a spiritual being, in order to account for the continued motion of matter, ‘which cannot move, unless it be moved; and cannot but move, when impelled by another.’ But if we look at the preceding page of Bishop Wilkins’ Principles of Natural Religion, we find the following argument for God’s absolute simplicity:

God cannot be compounded of any Principles, because the Principles and Ingredients which concur to the making of any thing, must be anteceddent to that thing. And if the Divine Nature were compounded, it would follow that there must be something in Nature antecedent to Him. Which is inconsistent with His being the First Cause. (Principles of Natural Religion, sixth edition, London, 1710, Chapter VIII, pp. 104-105.)

Since Paley was an Anglican divine who wrote admiringly of Bishop Wilkins and quoted from his apologetic works, it makes sense to assume that he would have endorsed Wilkins’ argument for God’s absolute simplicity, even if he does not explicitly refer to this argument in his Natural Theology.

If, on the other hand, we follow Duns Scotus in regarding God’s infinity, rather than His simplicity, as the central Divine-attribute generator, then a case for classical theism can be made simply by arguing that the Designer of Nature must be infinite. In that case, Paley can be legitimately said to have explicitly argued for the truth of classical theism, as he put forward no less than four arguments for God’s infinity in his Natural Theology.

Paley’s first argument was that God’s designs are infinitely more skillful than our own. Paley illustrated this point using the example of the human eye:

I know no better method of introducing so large a subject, than that of comparing a single thing with a single thing; an eye, for example, with a telescope. As far as the examination of the instrument goes, there is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it. (Chapter III, p. 18)

Were there no example in the world, of contrivance, except that of the eye, it would be alone sufficient to support the conclusion which we draw from it, as to the necessity of an intelligent Creator. It could never be got rid of; because it could not be accounted for by any other supposition, which did not contradict all the principles we possess of knowledge; the principles, according to which, things do, as often as they can be brought to the test of experience, turn out to be true or false. Its coats and humours, constructed, as the lenses of a telescope are constructed, for the refraction of rays of light to a point, which forms the proper action of the organ; the provision in its muscular tendons for turning its pupil to the object, similar to that which is given to the telescope by screws, and upon which power of direction in the eye, the exercise of its office as an optical instrument depends; the further provision for its defence, for its constant lubricity and moisture, which we see in its socket and its lids, in its gland for the secretion of the matter of tears, its outlet or communication with the nose for carrying off the liquid after the eye is washed with it; these provisions compose altogether an apparatus, a system of parts, a preparation of means, so manifest in their design, so exquisite in their contrivance, so successful in their issue, so precious, and so infinitely beneficial in their use, as, in my opinion, to bear down all doubt that can be raised upon the subject. (Chapter VI, pp. 75-76)

The formation then of such an image being necessary (no matter how) to the sense of sight, and to the exercise of that sense, the apparatus by which it is formed is constructed and put together, not only with infinitely more art, but upon the self-same principles of art, as in the telescope or the camera obscura. (Chapter III, p. 21)

Paley’s second argument was that God, when He was determining the laws of Nature, had to make a choice from among an infinite number of alternatives, only an infinitesimal proportion of which were compatible with the formation of a stable cosmos. Presumably, only a Being of infinite intelligence could be relied on to make such a selection and get it right:

Another thing, in which a choice appears to be exercised, and in which, amongst the possibilities out of which the choice was to be made, the number of those which were wrong, bore an infinite proportion to the number of those which were right, is in what geometricians call the axis of rotation. (Chapter XXII, p. 385)

… out of an infinite number of possible laws, those which were admissible for the purpose of supporting the heavenly motions, lay within certain narrow limits… (Chapter XX, p. 390)

Our second proposition is, that, whilst the possible laws of variation were infinite, the admissible laws, or the laws compatible with the preservation of the system, lie within narrow limits. (Chapter XXII, p. 393)

A third argument put forward by Paley is that God is able to control an indefinitely large region of space by His volitions. Since He is capable of controlling as large a region of space as he likes, we must suppose Him to be a Being of infinite power:

We have no authority to limit the properties of mind to any particular corporeal form, or to any particular circumscription of space. These properties subsist, in created nature, under a great variety of sensible forms. Also every animated being has its sensorium, that is, a certain portion of space, within which perception and volition are exerted. This sphere may be enlarged to an indefinite extent; may comprehend the universe; and, being so imagined, may serve to furnish us with as good a notion, as we are capable of forming, of the immensity of the Divine Nature, i. e. of a Being, infinite, as well in essence as in power; yet nevertheless a person. (Chapter XXIII, p. 409)

A fourth argument mounted by Paley for God’s infinity is that He is apparently capable of manifesting His wisdom and benevolence in an unlimited number of ways, upon an unlimited number of objects:

Whilst these propositions can be maintained, we are authorized to ascribe to the Deity the character of benevolence: and what is benevolence at all, must in him be infinite benevolence, by reason of the infinite, that is to say, the incalculably great, number of objects, upon which it is exercised. (p. 492)

Upon the whole; in every thing which respects this awful, but, as we trust, glorious change, we have a wise and powerful Being, (the author, in nature, of infinitely various expedients for infinitely various ends), upon whom to rely for the choice and appointment of means, adequate to the execution of any plan which his goodness or his justice may have formed, for the moral and accountable part of his terrestrial creation. (p. 548)

It is for all these reasons that Paley feels entitled to conclude that only a Being with infinite knowledge and power could have created the cosmos:

The degree of knowledge and power, requisite for the formation of created nature, cannot, with respect to us, be distinguished from infinite. (p. 445)

We have seen that Paley advances no less than four distinct arguments for God’s infinity in his Natural Theology. Some of these arguments are more convincing than others, but whatever their merit, they can certainly serve as a foundation for an argument leading to the God of classical theism, if Duns Scotus’ conception of the Divine attributes is correct.

I conclude, then, that the God of Paley’s Natural Theology is indeed the God of classical theism, even if Paley’s account of some of the Divine attributes differs in certain respects from that given by medieval Scholastic philosophers.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Paley on the Divine Attributes

If we examine Paley’s Natural Theology, we find that he explicitly affirms the vast majority of the attributes traditionally ascribed to God by Jews and Christians, as well as most of those ascribed to God by classical theists, and that he contradicts none of the claims of classical theism.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(a) The Designer of Nature is Transcendent

Paley explicitly affirms God’s transcendence in the following passage, where he declares that God is known through His effects, that His nature is wholly mysterious to us, and that His nature is far removed from all things that we can see:

The great energies of nature are known to us only by their effects. The substances which produce them, are as much concealed from our senses as the Divine essence itself. Gravitation, though constantly present, though constantly exerting its influence, though every where around us, near us, and within us; though diffused throughout all space, and penetrating the texture of all bodies with which we are acquainted, depends, if upon a fluid, upon a fluid which, though both powerful and universal in its operation, is no object of sense to us; if upon any other kind of substance or action, upon a substance and action, from which we receive no distinguishable impressions. Is it then to be wondered at, that it should, in some measure, be the same with the Divine nature?

Of this however we are certain, that whatever the Deity be, neither the universe, nor any part of it which we see, can be He… Nothing can be God, which is ordered by a wisdom and a will, which itself is void of; which is indebted for any of its properties to contrivance ab extra. The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412)

The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412)

…[A] power which could create such a world as this is, must be, beyond all comparison, greater than any which we experience in ourselves, than any which we observe in other visible agents; greater also than any which we can want, for our individual protection and preservation, in the Being upon whom we depend. It is a power, likewise, to which we are not authorized, by our observation or knowledge, to assign any limits of space or duration.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 444)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(b) The Designer of Nature is Uncaused, or Self-existent

Paley also explicitly affirmed God’s self-existence:

The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412)

“Self-existence” is another negative idea, viz. the negation of a preceding cause, as of a progenitor, a maker, an author, a creator.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 448)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(c) The Designer of Nature is the Cause of existence of everything in Nature

Paley declared God to be the cause of existence of all things occurring in Nature:

… I shall not, I believe, be contradicted when I say, that, if one train of thinking be more desirable than another, it is that which regards the phenomena of nature with a constant reference to a supreme intelligent Author. To have made this the ruling, the habitual sentiment of our minds, is to have laid the foundation of every thing which is religious. The world thenceforth becomes a temple, and life itself one continued act of adoration. The change is no less than this, that, whereas formerly God was seldom in our thoughts, we can now scarcely look upon any thing without perceiving its relation to him. Every organized natural body, in the provisions which it contains for its sustentation and propagation, testifies a care, on the part of the Creator, expressly directed to these purposes. We are on all sides surrounded by such bodies; examined in their parts, wonderfully curious; compared with one another, no less wonderfully diversified.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 539)

Against not only the cold, but the want of food, which the approach of winter induces, the Preserver of the world has provided in many animals by migration, in many others by torpor.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XVII, p. 298)

Under this stupendous Being we live. Our happiness, our existence, is in his hands. All we expect must come from him.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 541)

God is “the original cause of all things”

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 542)

…[T]he Creator must know, intimately, the constitution and properties of the things which he created; which seems also to imply a foreknowledge of their action upon one another, and of their changes; at least, so far as the same result from trains of physical and necessary causes. His omniscience also, as far as respects things present, is deducible from his nature, as an intelligent being, joined with the extent, or rather the universality, of his operations.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 444-445)

One and the self-same spring, acting in one and the same manner, viz. by simply expanding itself, may be the cause of a hundred different and all useful movements, if a hundred different and well-devised sets of wheels be placed between it and the final effect; e. g. may point out the hour of the day, the day of the month, the age of the moon, the position of the planets, the cycle of the years, and many other serviceable notices; and these movements may fulfil their purposes with more or less perfection, according as the mechanism is better or worse contrived, or better or worse executed, or in a better or worse state of repair: but in all cases, it is necessary that the spring act at the centre.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, pp. 416-417.)

Unconscious particles of matter take their stations, and severally range themselves in an order, so as to become collectively plants or animals, i.e. organized bodies, with parts bearing strict and evident relation to one another, and to the utility of the whole: and it should seem that these particles could not move in any other way than as they do; for, they testify not the smallest sign of choice, or liberty, or discretion. There may be particular intelligent beings, guiding these motions in each case: or they may be the result of trains of mechanical dispositions, fixed beforehand by an intelligent appointment, and kept in action by a power at the centre. But, in either case, there must be intelligence.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 420)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(d) The Designer of Nature is One

Paley argued for the unity of God at some length. For Paley, the uniformity of the laws of Nature constituted the best evidence of God’s unity:

Of the “Unity of the Deity,” the proof is, the uniformity of plan observable in the universe. The universe itself is a system; each part either depending upon other parts, or being connected with other parts by some common law of motion, or by the presence of some common substance. One principle of gravitation causes a stone to drop towards the earth, and the moon to wheel round it. One law of attraction carries all the different planets about the sun. This philosophers demonstrate. There are also other points of agreement amongst them, which may be considered as marks of the identity of their origin, and of their intelligent author. In all are found the conveniency and stability derived from gravitation… Nothing is more probable than that the same attracting influence, acting according to the same rule, reaches to the fixed stars: but, if this be only probable, another thing is certain, viz. that the same element of light does. The light from a fixed star affects our eyes in the same manner, is refracted and reflected according to the same laws, as the light of a candle. The velocity of the light of the fixed stars is also the same, as the velocity of the light of the sun, reflected from the satellites of Jupiter.

In our own globe, the case is clearer. New countries are continually discovered, but the old laws of nature are always found in them: new plants perhaps, or animals, but always in company with plants and animals which we already know; and always possessing many of the same general properties. We never get amongst such original, or totally different, modes of existence, as to indicate, that we are come into the province of a different Creator, or under the direction of a different will. In truth, the same order of things attend us, wherever we go.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXV, pp. 449-450)

The works of nature want only to be contemplated. When contemplated, they have every thing in them which can astonish by their greatness: for, of the vast scale of operation, through which our discoveries carry us, at one end we see an intelligent Power arranging planetary systems, fixing, for instance, the trajectory of Saturn, or constructing a ring of two hundred thousand miles diameter, to surround his body, and be suspended like a magnificent arch over the heads of his inhabitants; and, at the other, bending a hooked tooth, concerting and providing an appropriate mechanism, for the clasping and reclasping of the filaments of the feather of the humming-bird. We have proof, not only of both these works proceeding from an intelligent agent, but of their proceeding from the same agent; for, in the first place, we can trace an identity of plan, a connexion of system, from Saturn to our own globe: and when arrived upon our globe, we can, in the second place, pursue the connexion through all the organized, especially the animated, bodies which it supports. We can observe marks of a common relation, as well to one another, as to the elements of which their habitation is composed. Therefore one mind hath planned, or at least hath prescribed, a general plan for all these productions. One Being has been concerned in all.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, pp. 540-541)

If, in tracing these [secondary] causes, it be said, that we find certain general properties of matter which have nothing in them that bespeaks intelligence, I answer, that, still, the managing of these properties, the pointing and directing them to the uses which we see made of them, demands intelligence in the highest degree.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 419)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(e) The Designer of Nature is spiritual

Paley put forward both positive and negative arguments for why God must be a spirit:

“Spirituality” expresses an idea, made up of a negative part, and of a positive part. The negative part consists in the exclusion of some of the known properties of matter, especially of solidity, of the vis inertiae, and of gravitation. The positive part comprises perception, thought, will, power, action, by which last term is meant, the origination of motion; the quality, perhaps, in which resides the essential superiority of spirit over matter, “which cannot move, unless it be moved; and cannot but move, when impelled by another (Note: Bishop Wilkins’s Principles of Natural Religion, p. 106.).” I apprehend that there can be no difficulty in applying to the Deity both parts of this idea.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 448)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(f) The Designer of Nature is good

Paley devotes a whole chapter of his Natural Theology to the subject of God’s goodness:

|

Male lion (Panthera leo) and cub eating a Cape Buffalo in Northern Sabi Sand, South Africa. Photo by Luca Galuzzi. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

For Paley, predation posed an apparent difficulty for his claim that God is good, for the bodies of predators were clearly designed for the killing of other creatures. Paley’s answer to this difficulty was that these adaptations for killing were at least good for the animals possessing them (predators), and that in any case, nature needed some way to keep animal populations in check. As he put it: “Immortality upon this earth is out of the question. Without death there could be no generation, no sexes, no parental relation, i. e. as things are constituted, no animal happiness…. The term then of life in different animals being the same as it is, the question is, what mode of taking it away is the best even for the animal itself.” (Chapter XXVI, p. 473) Paley then argued that there would be even more animal pain in the world if animals were not killed by predators, because deaths from disease and starvation were slow and lingering: “Is it then to see the world filled with drooping, superannuated, half-starved, helpless, and unhelped animals, that you would alter the present system, of pursuit and prey?”

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, p. 474)

Paley believes he can establish God’s goodness by a process of elimination: both of the alternatives (God is evil, or God is indifferent) are absurd:

“When God created the human species, either he wished their happiness, or he wished their misery, or he was indifferent and unconcerned about either.

“If he had wished our misery, he might have made sure of his purpose, by forming our senses to be so many sores and pains to us, as they are now instruments of gratification and enjoyment: or by placing us amidst objects, so ill suited to our perceptions as to have continually offended us, instead of ministering to our refreshment and delight. He might have made, for example, every thing we tasted, bitter; every thing we saw, loathsome; every thing we touched, a sting; every smell, a stench; and every sound, a discord.”

“If he had been indifferent about our happiness or misery, we must impute to our good fortune (as all design by this supposition is excluded) both the capacity of our senses to receive pleasure, and the supply of external objects fitted to produce it.”

“But either of these, and still more both of them, being too much to be attributed to accident, nothing remains but the first supposition, that God, when he created the human species, wished their happiness; and made for them the provision which he has made, with that view and for that purpose.” (Chapter XXVI, pp. 465-466.)

Paley also puts forward two positive arguments for God’s goodness:

THE proof of the divine goodness rests upon two propositions; each, as we contend, capable of being made out by observations drawn from the appearances of nature.

The first is, “that, in a vast plurality of instances in which contrivance is perceived, the design of the contrivance is beneficial.”

The second, “that the Deity has superadded pleasure to animal sensations, beyond what was necessary for any other purpose, or when the purpose, so far as it was necessary,” might have been effected by the operation of pain.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, pp. 454-455)Contrivance proves design: and the predominant tendency of the contrivance indicates the disposition of the designer. The world abounds with contrivances: and all the contrivances which we are acquainted with, are directed to beneficial purposes. Evil, no doubt, exists; but is never, that we can perceive, the object of contrivance. Teeth are contrived to eat, not to ache; their aching now and then is incidental to the contrivance, perhaps inseparable from it: or even, if you will, let it be called a defect in the contrivance: but it is not the object of it. This is a distinction which well deserves to be attended to.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, p. 467)The two cases which appear to me to have the most of difficulty in them, as forming the most of the appearance of exception to the representation here given, are those of venomous animals, and of animals preying upon one another. These properties of animals, wherever they are found, must, I think, be referred to design; because there is, in all cases of the first, and in most cases of the second, an express and distinct organization provided for the producing of them. Under the first head, the fangs of vipers, the stings of wasps and scorpions, are as clearly intended for their purpose, as any animal structure is for any purpose the most incontestably beneficial. And the same thing must, under the second head, be acknowledged of the talons and beaks of birds, of the tusks, teeth, and claws of beasts of prey, of the shark’s mouth, of the spider’s web, and of numberless weapons of offence belonging to different tribes of voracious insects. We cannot, therefore, avoid the difficulty by saying, that the effect was not intended. The only question open to us is, whether it be ultimately evil. From the confessed and felt imperfection of our knowledge, we ought to presume, that there may be consequences of this economy which are hidden from us; from the benevolence which pervades the general designs of nature, we ought also to presume, that these consequences, if they could enter into our calculation, would turn the balance on the favourable side. Both these I contend to be reasonable presumptions.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, pp. 468-469)

The capacities, which, according to the established course of nature, are necessary to the support or preservation of an animal, however manifestly they may be the result of an organization contrived for the purpose, can only be deemed an act or a part of the same will, as that which decreed the existence of the animal itself; because, whether the creation proceeded from a benevolent of a malevolent being, these capacities must have been given, if the animal existed at all. Animal properties, therefore, which fall under this description, do not strictly prove the goodness of God: they may prove the existence of the Deity; they may prove a high degree of power and intelligence: but they do not prove his goodness; forasmuch as they must have been found in any creation which was capable of continuance, …

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, p. 482)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(g) The Designer of Nature is omnipresent

Paley argues that since human reason could assign no limits to the Designer’s power and knowledge, they could be regarded as infinite, for all practical intents and purposes. Moreover, since the laws of Nature hold in every nook and cranny of the cosmos, and since laws presuppose the existence of an intelligent agent, we may conclude that the Designer is omnipresent:

The Divine “omnipresence” stands, in natural theology, upon this foundation. In every part and place of the universe with which we are acquainted, we perceive the exertion of a power, which we believe, mediately or immediately, to proceed from the Deity. For instance; in what part or point of space, that has ever been explored, do we not discover attraction? In what regions do we not find light? In what accessible portion of our globe, do we not meet with gravity, magnetism, electricity; together with the properties also and powers of organized substances, of vegetable or of animated nature? Nay further, we may ask, What kingdom is there of nature, what corner of space, in which there is any thing that can be examined by us, where we do not fall upon contrivance and design? The only reflection perhaps which arises in our minds from this view of the world around us is, that the laws of nature every where prevail; that they are uniform and universal. But what do we mean by the laws of nature, or by any law? Effects are produced by power, not by laws. A law cannot execute itself. A law refers us to an agent. Now an agency so general, as that we cannot discover its absence, or assign the place in which some effect of its continued energy is not found, may, in popular language at least, and, perhaps, without much deviation from philosophical strictness, be called universal: and, with not quite the same, but with no inconsiderable propriety, the person, or Being, in whom that power resides, or from whom it is derived, may be taken to be omnipresent. He who upholds all things by his power, may be said to be every where present.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 445-446)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(h) The Designer of Nature is omnipotent

Paley advances two arguments for God’s omnipotence:

…[A] power which could create such a world as this is, must be, beyond all comparison, greater than any which we experience in ourselves, than any which we observe in other visible agents; greater also than any which we can want, for our individual protection and preservation, in the Being upon whom we depend. It is a power, likewise, to which we are not authorized, by our observation or knowledge, to assign any limits of space or duration.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 444)

We ascribe power to the Deity under the name of “omnipotence,” the strict and correct conclusion being, that a power which could create such a world as this is, must be, beyond all comparison, greater than any which we experience in ourselves, than any which we observe in other visible agents; greater also than any which we can want, for our individual protection and preservation, in the Being upon whom we depend.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 443-444)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(i) The Designer of Nature is omniscient

Paley argued for God’s omniscience, on the grounds that the creativity of His intellect appears to be infinitely versatile:

The degree of knowledge and power, requisite for the formation of created nature, cannot, with respect to us, be distinguished from infinite.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 445)

…[T]he same sort of remark is applicable to the term “omniscience,” infinite knowledge, or infinite wisdom. In strictness of language, there is a difference between knowledge and wisdom; wisdom always supposing action, and action directed by it. With respect to the first, viz. knowledge, the Creator must know, intimately, the constitution and properties of the things which he created; which seems also to imply a foreknowledge of their action upon one another, and of their changes; at least, so far as the same result from trains of physical and necessary causes. His omniscience also, as far as respects things present, is deducible from his nature, as an intelligent being, joined with the extent, or rather the universality, of his operations. Where he acts, he is; and where he is, he perceives. The wisdom of the Deity, as testified in the works of creation, surpasses all idea we have of wisdom, drawn from the highest intellectual operations of the highest class of intelligent beings with whom we are acquainted; and, which is of the chief importance to us, whatever be its compass or extent, which it is evidently impossible that we should be able to determine, it must be adequate to the conduct of that order of things under which we live. And this is enough.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 444-445)

… we have a wise and powerful Being, (the author, in nature, of infinitely various expedients for infinitely various ends), upon whom to rely for the choice and appointment of means, adequate to the execution of any plan which his goodness or his justice may have formed, for the moral and accountable part of his terrestrial creation.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 548)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(j) God is simple

Paley emphatically argued for God’s simplicity in a passage in his Natural Theology, where he defines a contrivance as a co-ordinated arrangement of parts subserving some end. A contrivance requires a Designer. Since God, by definition, has no Designer, it follows that God cannot be composed of carefully co-ordinated parts – for if He were, then He would no longer be self-existent. Hence Paley must have been affirming God’s simplicity when he wrote the following:

Of this however we are certain, that whatever the Deity be, neither the universe, nor any part of it which we see, can be He. The universe itself is merely a collective name: its parts are all which are real; or which are things. Now inert matter is out of the question: and organized substances include marks of contrivance. But whatever includes marks of contrivance, whatever, in its constitution, testifies design, necessarily carries us to something beyond itself, to some other being, to a designer prior to, and out of, itself. No animal, for instance, can have contrived its own limbs and senses; can have been the author to itself of the design with which they were constructed. That supposition involves all the absurdity of self-creation, i. e. of acting without existing. Nothing can be God, which is ordered by a wisdom and a will, which itself is void of; which is indebted for any of its properties to contrivance ab extra. The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see. Which consideration contains the answer to a question that has sometimes been asked, namely, Why, since something or other must have existed from eternity, may not the present universe be that something? The contrivance perceived in it, proves that to be impossible. Nothing contrived, can, in a strict and proper sense, be eternal, forasmuch as the contriver must have existed before the contrivance.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412-413).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(k) God is beyond space and time

For Paley, a being is eternal if it exists, and if it has no beginning or end:

“Eternity” is a negative idea, clothed with a positive name. It supposes, in that to which it is applied, a present existence; and is the negation of a beginning or an end of that existence.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 447)

We have seen that for Paley, God is unlimited, and hence beyond the bounds of space and time. However, whether Paley actually believed that God is timeless and immutable is more debatable. Passages can be found in his writings which appear at first glance to suggest that he envisaged God as everlasting, rather than timeless:

Nothing contrived, can, in a strict and proper sense, be eternal, forasmuch as the contriver must have existed before the contrivance.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 413)

There may be particular intelligent beings, guiding these motions in each case: or they may be the result of trains of mechanical dispositions, fixed beforehand by an intelligent appointment, and kept in action by a power at the centre.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 420)

In strictness, however, we have no concern with duration prior to that of the visible world. Upon this article therefore of theology, it is sufficient to know, that the contriver necessarily existed before the contrivance.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 447-448)

It would be unwise to conclude too much from these passages, however. We should recall that Scripture itself speaks of God as existing before His creation, as the following examples show:

Before the mountains were born or you brought forth the earth and the world, from everlasting to everlasting you are God. (Psalm 90:2)

“I was appointed from eternity,

from the beginning, before the world began.

When there were no oceans, I was given birth,

when there were no springs abounding with water;

before the mountains were settled in place,

before the hills, I was given birth,

before he made the earth or its fields

or any of the dust of the world. (Proverbs 8:23-26, speaking of the Wisdom of God)“Father, I want those you have given me to be with me where I am, and to see my glory, the glory you have given me because you loved me before the creation of the world. (John 17:24)

For he chose us in him before the creation of the world to be holy and blameless in his sight. (Ephesians 1:4)

He was chosen before the creation of the world, but was revealed in these last times for your sake. (1 Peter 1:20)

Further support for the view that Paley affirmed God’s absolute immutability comes from the fact that Paley approvingly quotes from Bishop Wilkins’ Principles of Natural Religion in Chapter XXIV of his Natural Theology, when arguing for God’s spirituality. In chapter VIII of his apologetic work, on pages 115-117, Wilkins emphatically affirms his belief in God’s absolute immutability, approvingly quotes the pagan philosophers Seneca and Plato in support of the doctrine, and approvingly cites the argument put forward by Plato for God’s immutability in Book II of his Republic: if God were capable of change, it would have to be either externally imposed (which is impossible, as nothing can necessitate a change in God) or voluntary, and if the latter, either a change for the better or a change for the worse – both of which are incompatible with God’s perfection. Wilkins then puts forward his own argument for God’s immutability:

We esteem Changeableness in Men either an Imperfection, or a Fault. Their Natural Changes, as to their Persons, are from Weakness and Vanity; their Moral Changes, as to their Inclinations and Purposes, are from Ignorance and Inconstancy. And therefore there is very good reason why we should remove this from God, as being that which would darken all his other Perfections. The greater the Divine Perfections are, the greater Imperfection would Mutability be. Besides, that it would take away the foundation of all religion, Love and Fear, and Affiance, and Worship: In which Men would be very much discouraged, if they could not certainly rely upon God, but were in doubt that His Nature might alter, and that hereafter he might be quite otherwise from what we now apprehend him to be.

(Of the Principles and Duties of Natural Religion, sixth edition, London, 1710, Chapter VIII, p. 117.)

Given the forcefulness of the above passage, the default assumption must be that Paley, who was familiar with it, espoused the traditional Christian doctrine of God’s absolute immutability.

Additionally, there are passages in Paley’s Natural Theology which lend support to the view that he envisaged God as being absolutely immutable. For instance, Paley argues that God is beyond the limits of space and time, which would suggest that he viewed God as being atemporal:

…[A] power which could create such a world as this is, must be, beyond all comparison, greater than any which we experience in ourselves, than any which we observe in other visible agents; greater also than any which we can want, for our individual protection and preservation, in the Being upon whom we depend. It is a power, likewise, to which we are not authorized, by our observation or knowledge, to assign any limits of space or duration.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 444)

In the two passages below, Paley also argues that God is the ultimate originator of motion, which would imply that He is outside time:

The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412)

“Spirituality” expresses an idea, made up of a negative part, and of a positive part. The negative part consists in the exclusion of some of the known properties of matter, especially of solidity, of the vis inertiae, and of gravitation. The positive part comprises perception, thought, will, power, action, by which last term is meant, the origination of motion; the quality, perhaps, in which resides the essential superiority of spirit over matter, “which cannot move, unless it be moved; and cannot but move, when impelled by another (Note: Bishop Wilkins’s Principles of Natural Religion, p. 106.).” I apprehend that there can be no difficulty in applying to the Deity both parts of this idea.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 448)

I can only conclude that Paley did indeed hold to the doctrine of Divine immutability, even if he did not elaborate on the point in his Natural Theology.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Two ways in which Paley differed from traditional classical theism

Somewhat oddly, Paley interprets God’s attribute of necessity to mean nothing more than the fact that His existence can be established by us:

“Necessary existence” means demonstrable existence.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 448 – Attributes of God)

However, Paley notion of God’s self-existence corresponds closely to the way in which traditional believers would define God’s necessity:

“Self-existence” is another negative idea, viz. the negation of a preceding cause, as of a progenitor, a maker, an author, a creator.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 448 – Attributes of God)

Paley also appears to deny the impassibility of God, in the strict sense of the word, as he ascribes perceptions to Him:

IT is an immense conclusion, that there is a GOD; a perceiving, intelligent, designing, Being; at the head of creation, and from whose will it proceeded. The attributes of such a Being, suppose his reality to be proved, must be adequate to the magnitude, extent, and multiplicity of his operations: which are not only vast beyond comparison with those performed by any other power, but, so far as respects our conceptions of them, infinite, because they are unlimited on all sides.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 441-442)

…[T]he Creator must know, intimately, the constitution and properties of the things which he created; which seems also to imply a foreknowledge of their action upon one another, and of their changes; at least, so far as the same result from trains of physical and necessary causes. His omniscience also, as far as respects things present, is deducible from his nature, as an intelligent being, joined with the extent, or rather the universality, of his operations. Where he acts, he is; and where he is, he perceives.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, pp. 444-445)

Nowhere, however, does God claim that God experiences bodily feelings, such as pain. On the contrary, Paley insists that God is a spirit. Thus Paley clearly accepts impassibility in the broad sense of the term.