Reverend Fathers,

Since the Pope’s upcoming encyclical on the environment, Laudato Si, is due to be released later this month, I’m sure you will be very busy telling the world’s 1.2 billion Catholic laypeople (including myself) what the encyclical means. My reason for writing this post is that while most people (including members of the clergy) are quite well-informed about the science of global warming, they tend to be poorly informed about the solutions to the problem of man-made global warming, as well as the costs of implementing those solutions. Some of you may think that these are technical issues, which the clergy need not concern themselves with. But Scripture itself counsels us to be prudent servants of the Lord, and not foolish ones. If God has given us a job to do of cleaning up the planet, then we had better not squander precious resources on impractical pipe-dreams, because every dollar wasted is a dollar that could have been spent on helping someone in need – and right now, there are billions who are in need. An additional reason for my writing to you is that the worldwide effort to combat global warming is bound to generate some acute moral dilemmas, which most people have heard very little about – and some of them will ask you for spiritual guidance and advice. To make matters worse, the built-in uncertainties in global warming predictions render the moral calculus even more complicated. Finally, I have to say that some of the theological arguments which have been put forward by Christians to justify the fight against global warming rest on flawed premises. Religion is not served by poor arguments, and I believe that if we are going to care for the environment, then we need to do it for the right reasons. That’s why I’ve decided to write to you.

Since most of you have never heard of me, I’d better introduce myself. My name is Vincent Torley, and I’m an Australian Catholic layman (now residing in Japan), with a Ph.D. in philosophy. My Webpage is here. I should mention that I am well-acquainted with the animal rights movement and that I have read fairly widely in the field of environmental ethics. While I am not a scientist, I do have an academic background in science: my first degree was a B.Sc. degree, my M.A. in philosophy was on the subject of scientific laws (laws of nature), and my Ph.D. (for which I had to peruse hundreds of scientific papers) was on the topic of animal minds. I don’t claim any expertise on global warming; however, much of what I’ve read about the solution to the problem of global warming strikes me as naively optimistic. On top of that, my background in economics has lent me an additional perspective on global warming, and over the years, I’ve managed to dig up some information about the costs of fighting global warming which I think will interest the Catholic clergy. I am also the author of a free pro-life electronic book, titled, Embryo and Einstein – Why They’re Equal (2011). In Section I of my e-book, I provide a detailed scientific rebuttal of the argument, put forward by many ecologists, that overpopulation and environmental destruction make abortion and population control a practical necessity. Finally, I should mention that three months ago, I sent a letter to four Catholic cardinals and one Apostolic nuncio, regarding Pope Francis’ upcoming encyclical on the environment.

In this post, I’ll be assuming that the predictions on global warming made by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change are correct. I’ll briefly discuss the uncertainties in these predictions towards the end of my article, but I should declare at the outset that I fully accept that most of the warming that the Earth has experienced since the late 1970s is man-made. How much warming will occur in the future as carbon dioxide levels rise is a separate issue, but I’m quite prepared to grant that there’s a significant risk, based on what we currently know, that the amount of warming will pose a real danger to Earth’s ecosystems.

Executive Summary

For the benefit of those who would simply like to know the key conclusions I’ve reached, here’s a nine-point summary:

1. If the IPCC’s global warming predictions are correct, then we have just 50 years to reduce worldwide greenhouse gas emissions to zero. That’s right: zero. After that, we’ll also have to scrub a lot of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, to bring it back to a safe level of 350 parts per million. This will be a Herculean task.

2. Nuclear power is the only technology which has a realistic chance of replacing fossil fuels and bringing worldwide greenhouse gas emissions down to zero within the next 50 years. Unfortunately, nuclear power is politically unpopular in many Western countries because of anti-nuclear hysteria whipped up by the green movement, despite the fact that nuclear power is the safest form of energy in the world. (In fact, it’s even safer than wind and solar energy.) If we built nuclear reactors around the world at the same pace that Sweden did between 1960 and 1990, we could close down all coal and natural gas power plants in just 25 years. However, history shows that new energy sources always take several decades to become widely adopted, for a host of complex reasons that have more to do with politics than technology. Still, we have at least a fighting chance of reducing worldwide greenhouse gas emissions to zero within 50 years, using nuclear power.

3. Despite falling costs, new energy storage technologies and government subsidies of over $100 billion a year, renewable energy sources will be unable to replace fossil fuels within the next 50 years, for several reasons. In brief: renewable energy sources provide a very poor energy return on the energy invested in building them, they require vast amounts of land, they generate lots of pollution (especially in the case of solar energy and biomass) and they cannot be economically scaled up to meet worldwide demand. In the words of Professor James Hansen, former Vice-President Al Gore’s climate adviser: “Suggesting that renewables will let us phase rapidly off fossil fuels in the United States, China, India, or the world as a whole is almost the equivalent of believing in the Easter Bunny and Tooth Fairy.”

4. The cost of fighting global warming will be astronomical: $44 trillion on a very optimistic estimate, but more realistically, at least $100 trillion, making it 1,000 times more expensive than the Apollo program, in today’s dollars. (One professor of economics has even described the cost of fighting global warming as incalculable.) To meet this cost, middle-income and advanced countries may have to pay up to 4% of their GDP, over a period of several decades. Media claims that fighting global warming will have a negligible impact on GDP growth are based on economically flawed reasoning, and reports claiming that combating global warming will actually save us money have been criticized for their over-optimistic assumptions. Some economists claim that relacing fossil fuels with nuclear power and/or renewable energy will actually increase countries’ GDP, but the truth is that we really don’t know. In short: scientists and economists are not certain whether we even have enough money to stop global warming, within the time available.

5. Meanwhile, the world is still struggling to meet its United Nations Millennium Development Goals, as millions of people (mostly children) continue to die each year as a result of malnutrition, while billions more lack even basic sanitation. Whatever we decide to do about global warming, the needs of these people must come first. Duties to people dying here and now takes precedence over any moral considerations relating to as-yet-unconceived children.

6. While it’s reasonably certain that the rise in global temperatures since the late 1970s has been largely man-made, what’s not certain is how much temperatures will eventually rise in the future, as a result of further greenhouse gas emissions – in other words, the equilibrium climate sensitivity. The scientific disagreement on this subject relates not to the effects of carbon dioxide but to the feedback effects of water vapor, which the IPCC claims will magnify the effects of carbon dioxide increases by a factor of two, three or four, or even six. (At least, that’s what the vast majority of the IPCC’s computer models predict.) When we look at the actual data, though, the warming trend is much more gradual, suggesting that a doubling of CO2 levels due to man-made greenhouse gas emissions could lead to a modest long-term rise in global temperatures of about 1.6 degrees above pre-industrial levels. If that’s the case, then there’s no need for a costly all-out blitz against global warming: we will have a few more decades to design better technology to solve the problem in a more rational manner, before it poses a serious threat to the biosphere. As one of Aesop’s fables puts it, “Slow and steady wins the race.”

7. So, who’s to blame for global warming? The short answer is that we are – consumers, especially those in affluent Western countries. The richest 7% of the world’s population is responsible for 50% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Blaming big multinational corporations for global warming makes no sense, because the goods and services these corporations supply are simply those which people want to buy, and the prices they sell them for are the prices that people are willing to pay. If corporations cut corners, avoid complying with environmental regulations, and pollute the environment without paying for the damage they cause, that’s because consumers, who buy their goods, are unwilling to pay for the costs of producing those goods in an ethical manner. In the words of a Pogo comic strip, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Finally, the naive tendency of certain ecologists to blame global warming on overpopulation overlooks the fact that the poorest one-sixth of the world’s population, whose growth rate tends to be the highest, produces virtually no ecological footprint. What’s more, even when we calculate the pollution generated by these people’s future descendants, it turns out that people in affluent countries leave a bigger ecological footprint: a child born in the United States today will, down the generations, generate an ecological footprint which is seven times that of an extra Chinese child, 46 times that of a Pakistani child, 55 times that of an Indian child, and 86 times that of a Nigerian child.

In short: the real cause of global warming today is neither population nor big corporations, but increasing human wealth, which fuels consumer demand. But it does not have to be this way. The wealth generated by capitalism is by no means a bad thing: after all, it got us out of a never-ending cycle of poverty, scarcity, hunger and high infant mortality. A country’s wealth can also be invested in creating the technology that will solve the problem of global warming. And without wealth, I might add, none of the technology we enjoy today would even be possible.

8. Whether we like it or not, global warming raises a host of troubling moral issues. For example, if it’s a sin, then who is it a sin against – God? humanity? future generations? the biosphere? And how big a sin is it? What distinguishes a mortal environmental sin from a venial one? Moreover, if global warming is a sin, then at what point in history did it become a sin? Surely not before 1980 – for it wasn’t until then that a scientific consensus began to emerge that it was taking place. However, the industrialization of China did not take place until after the 1980s. It generated a lot of greenhouse gas emissions, but also lifted 600 million people out of poverty. Was that a bad thing? And what about India in the 21st century? Doesn’t it have a right to industrialize too? Also, if global warming is (as we have seen) primarily caused by affluent consumption, then exactly what are we supposed to give up, to save the planet? For most U.S. households, the single largest source of carbon dioxide emissions comes from driving, followed by housing and food. So, should we give up owning cars and switch to public transport and/or car pooling? Since food is the third-largest source of household greenhouse gas emissions, and since vegetarians and fish-eaters have a carbon footprint which is only about half that of high meat-eaters, should we all give up meat, then? An additional moral problem for global warming is that the cost of eliminating this problem is admitted by some senior scientists to be incalculable. In that case, someone might argue that we can’t possibly have a moral duty to fight global warming – for if we did, that would seem to imply that we have an unlimited obligation. Finally, if global warming is a problem we urgently need to fight now, then it could be argued that parents (especially in affluent countries, but also in rapidly rising middle-income countries, like China) have a moral obligation to forego having large families until we have won the battle against global warming, as these parents are only adding to humanity’s carbon footprint in the mean time, by procreating more children who will consume a lot when they are adults (as will their children). Such a conclusion, however, runs totally contrary to Catholic, Orthodox and Jewish tradition, which views large families as a blessing, rather than a curse.

9. The theological arguments put forward by certain clerics in support of the crusade against global warming are badly flawed. For instance, it is simply incorrect to claim that man was meant by God to “tend and keep” the Earth; on the contrary, he was clearly and expressly told to “subdue” and “have dominion” over it (Genesis 1:28). The verbs used here are very powerful ones (see here and here). There’s no doubt that the Bible views human beings as the lords of the Earth, governing it in God’s place. It was the Garden of Eden, not the Earth, that Adam and Eve were supposed to tend (Genesis 2:15), and after they sinned, they were evicted from the Garden, never to return (Genesis 3:23-24). Nor can one liken man’s relation to creation to that of a shepherd, caring for his sheep, as some have suggested: for if that were the case, then we would have no right to eat or intentionally kill any living creature. (Shepherds don’t kill the sheep in their flock; their job is to guard the flock and if necessary, lay down their life for the sheep which they protect.)

A better argument for conservation, advanced recently by Pope Francis, is that we are morally bound to respect God’s creation – which means that we may not destroy it wantonly. However, as the lords of creation, we do have the authority to engage in acts which result in unintended environmental harm, if there is a proportional reason for doing so. I would argue that the fight against Third World poverty is one such reason.

That concludes my Executive Summary. I’d now like to address each of the nine points listed above, in greater depth.

1. IPCC: We have just 50 years to bring the world’s greenhouse gas emissions to a dead halt

If we want to achieve the drastic cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions recommended by the IPCC, then we haven’t a moment to lose. Countries around the world will need to co-operate as never before in the course of human history. Cutting emissions will require a massive technological push, and we’ll also probably need to pull carbon out of the atmosphere. Doing all that in the space of just 50 years will be a Herculean feat, making it by far the most difficult task that humanity has ever undertaken. To put the problem in perspective: the Apollo program cost $110 billion altogether, in today’s dollars. Fighting global warming could cost 1,000 times more than that, for reasons that I’ll explain in section 4, below.

Assuming that the IPCC’s global warming projections are correct, if we want to have a better-than-even chance of staying below the internationally recognized “danger threshold” of 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels (which we’re due to cross in 2036 if we continue to burn fossil fuels at the current rate), then we’ll have to reduce worldwide greenhouse gas emissions to ZERO by 2070, and after that, we’ll have to scrub quite a lot of CO2 out of the atmosphere, to bring the concentration down to a safe level of 350 parts per million. (It’s already over 400 ppm.) And I should add that the “danger threshold” of 2 degrees may well be too lax: many climate experts now argue that it should really be 1.5 degrees. Achieving this target would be dauntingly difficult: greenhouse gas emissions would have to peak in 2014 and then decline (in all-gas terms) by as much as 7.1% per year, compared with an annual decline of 3.4% per year if the 2 degree-Celsius-target is to be met.

Right now, the world is currently failing badly right now at meeting its climate goals, as Vox senior editor Brad Plumer points out in his online article, How to stop global warming, in 7 steps. Greenhouse gas emissions did not rise in 2014 (for the first time in 40 years), but they did not fall either, and many of the countries which signed the Kyoto Protocol have failed to meet their targets, and of the countries which met their targets, most were Eastern European countries whose economies and industries had collapsed (which means that the “reductions” were really only temporary falls), while others, such as Britain, had simply moved their carbon-intensive industries (such as steel and aluminium manufacturing) off-shore to countries not covered by the Protocol, prompting Oxford energy economist Dieter Helm to ask, “What exactly is the point of reducing emissions in Europe if it encourages energy-intensive industry to come to China, where the pollution will be even worse?” Finally, claims that China’s carbon emissions fell in 2014 should be treated with caution.

2. Nuclear power is the only known way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to zero in the next few decades

|

Nuclear Energy Systems Deployable no later than 2030 and offering significant advances in sustainability, safety and reliability, and economics. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

There’s only one way that scientists know of, which would enable us to achieve the target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2070: replace all fossil fuels with nuclear energy. (I’ll discuss the technological problems with renewable energy sources in the following section.)

A nuclear-powered planet is technologically feasible, within the next 30 years

If countries around the world built nuclear plants at the same rate that Sweden did Sweden did between 1960 and 1990, all coal and natural gas power plants could be phased out in just 25 years, cutting worldwide human carbon emissions by half, according to a new study published in PLoS ONE by Staffan Qvist, a physicist at Uppsala University in Sweden, and Barry Brook, a Professor of Environmental Sustainability at the University of Tasmania (Potential for Worldwide Displacement of Fossil-Fuel Electricity by Nuclear Energy in Three Decades on Extrapolation of Regional Deployment Data. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0124074. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124074). Ross Pomeroy has written a highly readable summary of the study’s central conclusions, in an article for RealClearScience.

In reality, however, Qvist and Brook’s estimate is almost certainly far too optimistic: unlike the computer industry, where a doubling in the computing power of microchips has occurred about every two years, transitions in the energy industry are relatively slow. Even oil took 40 years to get from 5 percent of the world’s primary energy supply to 25 percent.

Why a global transition to nuclear power will be politically difficult to implement

However, while a switch to nuclear energy over the next few decades is technically feasible, it’s going to be politically difficult to accomplish. In Western countries, the only demographic that’s keen on nuclear energy is white, middle-aged men, who tend to believe that the risks can be controlled. Women, young people and minorities, on the other hand, tend to be distrustful of nuclear energy, owing to its perceived risks – which is sad, as it’s one of the safest forms of energy in the world: nuclear power actually prevented over 1.8 million net deaths worldwide between 1971-2009, according to a study by NASA scientists Pushker Kharecha and James Hansen. Even after taking account of the Fukushima nuclear accident, the authors conclude that replacing nuclear energy with coal or gas between now and 2050 (as some members of the green movement advocate) would result in an extra 420,000 to 7 million deaths, worldwide. And an online study by author and entrepreneur Seth Godin which compares deaths per Terawatt Hour of energy produced for various sources of energy concludes that nuclear power is the safest – even safer than solar, wind and hydroelectricity – while coal is by far the most dangerous, followed by oil, biofuels and natural gas.

Regarding the nuclear accident at Fukushima, climatologist and global warming activist James Hansen observes:

Fukushima nuclear power plants are a 50-year-old technology. They withstood a powerful earthquake, but were washed over by a 10-meter tsunami that wiped out the power sources used to cool the reactors. Modern 3rd generation light-water reactors can use passive cooling systems that require no power source. No people died at Fukushima because of the nuclear technology.

Tragically, in Western countries, the economic viability of nuclear power has been sabotaged by legal “red tape” imposed by environmentalists, politicians and regulators, as Dr. Matt Ridley, former science editor of The Economist, explains in a blog article titled, Fossil fuels are not finished, not obsolete, not a bad thing (March 22, 2015). The effect of this costly litigation has been to make nuclear plants into “huge and lengthy boondoggles.” As a result, writes Ridley, “The world’s nuclear output is down from 6% of world energy consumption in 2003 to 4% today. It is forecast to inch back up to just 6.7% by 2035, according the Energy Information Administration.”

Middle-income and developing countries are more enthusiastic about nuclear energy than Western countries, with 60 plants now under construction in countries like China, Russia, India and Pakistan, and 160 more planned and a further 300 proposed, according to a press release by the World Nuclear Association. I should mention that He Zuoxiu, a leading Chinese scientist who worked on China’s nuclear weapons program, has voiced concerns about China’s plans for a rapid expansion of nuclear power plants, calling them “insane” because the country is not investing enough in safety controls. For a very different perspective on the safety standards of China’s nuclear program, readers might like to have a look at this report by the World Nuclear Association on China’s nuclear program.

What we need to do

Western countries need to embrace nuclear technology and provide more assistance to developing countries with the development of nuclear power plants, if we are to have a good chance of slashing worldwide greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2070. There are some signs for hope: a new survey of Americans shows that 68% favor nuclear energy, while 78% consider nuclear energy important to meet the country’s future electricity needs. And in Japan, a new government proposal, which is due to be ratified in July 2015, aims to cover 20 to 22% of Japan’s energy demands from nuclear energy by 2030. Meanwhile, India aims to supply 25% of its electricity from nuclear energy by 2050. China’s nuclear program is projected to grow by 11% per annum over the next 20 years, according to BP’s Energy Outlook 2035. On the other hand, the report also anticipates that nuclear power’s share of the energy supply in the USA and Europe will fall, as aging nuclear power plants are decommissioned, and it expects renewables (including biofuels) to overtake nuclear power worldwide by the early 2020s. That would be a tragic mistake, for reasons that I’ll now explain.

3. Why wind and solar power won’t be enough to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2070

|

Part of the 354 MW Solar Energy Generating Systems (SEGS) parabolic trough solar complex in northern San Bernardino County, California. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

| KEY POINTS: (1) High usage of renewable energy sources is associated with technologically primitive societies, not advanced ones. (2) Only a small percentage of the world’s energy supply comes from renewable sources – and most of that energy is hydroelectric power. Wind and solar make up just over 1% of the global energy mix. (3) Moore’s law does not apply to renewable energy sources. There’s absolutely no reason to expect an exponential doubling if the renewable energy supply every few years, in the decades to come. (4) There are three compelling reasons why renewables cannot supply most of the world’s energy within the next 50 years: the energy returned on energy invested is too low for them to be commercially viable; they can’t be economically scaled up; and they generate a large amount of environmental damage (especially solar and biofuels). Additionally, they require vast amounts of land. (5) Professor Mark Jacobson’s plan for a world whose energy needs can be met entirely by renewable sources is detailed and well-costed, but wildly impractical. (6) Innovation won’t change world energy usage overnight. Worldwide changes in patterns of energy usage always take several decades to accomplish. |

Renewable energy sources, such as solar energy and wind energy, won’t be able to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to zero by the year 2070. This news might come as a shock to many readers, following the recent spate of rosy media reports claiming that the cost of solar panels is coming down, that solar energy use is growing by leaps and bounds, and that solar energy is on the verge of achieving “grid parity“, which will make it cost-competitive with fossil fuels by 2017. Unfortunately, reports of the death of the fossil fuel industry are premature, for several reasons.

Background: renewables supplied most of the world’s energy until the late nineteenth century, and still supply most of Africa’s energy

In a thought-provoking article titled, The Decline of Renewable Energy (Project Syndicate, August 14, 2013), Professor Bjorn Lomborg, a Danish statistician and the founder of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, points out that back in the year 1800, the world obtained 94% of its energy from renewable sources – a figure which has been declining ever since, until very recently. Lomborg makes another telling observation: “The most renewables-intensive places in the world are also the poorest. Africa gets almost 50% of its energy from renewables, compared to just 8% for the OECD.”

And what about China, which has lifted 600 million people out of poverty since the 1980s? Lomborg writes: “In China, renewables’ share in energy production dropped from 40% in 1971 to 11% today; in 2035, it will likely be just 9%.”

Today, we are accustomed to viewing fossil fuels as an unmitigated evil, while renewables are regarded as an unalloyed good. Professor Lomborg sees things very differently:

Burning wood in pre-industrial Western Europe caused massive deforestation, as is occurring in much of the developing world today. The indoor air pollution that biomass produces kills more than three million people annually. Likewise, modern energy crops increase deforestation, displace agriculture, and push up food prices…

The momentous move toward fossil fuels has done a lot of good. Compared to 250 years ago, the average person in the United Kingdom today has access to 50 times more power, travels 250 times farther, and has 37,500 times more light. Incomes have increased 20-fold.

Today, only a small percentage of the world’s energy comes from renewable sources -and wind and solar provide only 1%

Right now, only about 11% of world marketed energy consumption comes from renewable energy sources, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), and most of that comes from hydro power, with solar and wind making up around 2% together. The current global energy mix consists of oil (36%), natural gas (24%), coal (28%), nuclear (6%), hydro (6%) and other renewable energy sources such as biomass, wind and solar (about 2%). (The BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2014 can be viewed here.)

Solar and wind energy proponents often cite figures showing that solar energy makes up a large percentage of the electricity supply in many European countries, such as Sweden, which has Sweden has the highest percentage of renewable energy in the EU (over 47 per cent), and Denmark, which gets 43 percent of its energy from renewable sources and aims to meet 100 percent of its energy needs with renewables by 2050. (Germany, which gets 27 percent of its electricity from renewables, has not been so successful: due to its decision to abandon nuclear energy in 2011 after the nuclear accident in Fukushima, the country actually burns more coal than five years ago, has some of the highest household electricity bills in the developed world and will miss its 2020 greenhouse gas emission targets.) However, Europe is not the world, and electricity makes up only a small part of the energy we consume. According to International Energy Association figures, electricity makes up less than a fifth of the world’s energy consumption, comprising just 18.1% of total final consumption in 2012. And if we look at the world’s total primary energy supply for 2012, we find that 31% came from oil, 29% from coal, 21% from natural gas, 10% from biofuels and waste, 5% from nuclear energy, 2% from hydroelectricity, and just over 1% from geothermal, solar, wind and waste, according to official IEA figures for 2014. Even today, solar energy provides just 0.4% of the total energy consumed in the United States.

Why Moore’s law doesn’t apply to renewable energy

Technological optimists might respond by citing Moore’s law: for the past fifty years, the number of transistors (building blocks) on an integrated circuit (computer chip or microchip) has doubled every two years. If solar energy were to progress at the same rate, then even though solar energy makes up only about 0.5% of the world energy market now, it would make up 100% of the market in just eight years.

Rhodes scholar and physicist Dr. Varun Sivaram rebuts this naive optimism in an online article titled, Why Moore’s Law Doesn’t Apply to Clean Technologies. Dr. Sivaram identifies three key differences between advances in computer chip technology and advances in solar energy:

To date, there have been three crucial differences between Moore’s law for microchips and the historical cost declines of solar panels and batteries:

1.Moore’s Law is a consequence of fundamental physics. Clean technology cost declines are not.

2.Moore’s Law is a prediction about innovation as a function of time. Clean technology cost declines are a function of experience, or production.

3.**Why this all matters** Moore’s Law provided a basis to expect dramatic performance improvements that shrank mainframes to mobile phones. Clean technology cost declines do not imply a similar revolution in energy.

The three massive problems that renewable energy faces

There are three compelling reasons why renewable energy alone will not be able to replace fossil fuels, over the next 50 years.

(a) The energy returned on energy invested is too low for renewable energy sources to be viable

First, as Professor John Morgan helpfully explains in an online article titled, The Catch-22 of Energy Storage, the ratio of energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) for solar and wind power plants is far too low for them to be viable as power sources in Western countries. Obviously, the energy you get out of a power plant has to exceed the energy invested in building the plant, or it wouldn’t be worthwhile constructing it in the first place. But if you want to live in a society that builds things like roads and bridges,trucks that can transport food from farms to cities, schools for educating children, health care centers and art museums, then you need power plants that yield a lot more energy: at least 7 times as much as the energy invested in building those plants originally. And if you need to rely on batteries to store the energy you generate, then the EROEI needs to be even higher than 7:1. In his article, Professor Morgan explains that For nuclear power, by contrast, the ratio of energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) is very high (about 75:1), making it a viable proposition. What about renewables? With the exception of hydroelectricity, only concentrated solar power has an EREOI greater than 7:1. All other renewable sources examined in the article (wind, solar photovoltaic and biomass) are non-viable. The EROEI for concentrated solar power is 9:1, making it viable, provided that it is coupled with pumped hydroelectric power, to store the excess energy it produces, so that it can still be used when the sun isn’t shining. However, hydroelectric storage around the world is limited by the need for suitable geography, and for that reason, even concentrated solar power (which produces just 2.4% of the world’s solar energy output) would have to rely on energy-intensive battery storage. That would effectively reduce its EROEI below the minimum threshold of 7:1, making it non-viable, too. In his article, Professor Morgan cites a report by Weißbach et al., titled, Energy intensities, EROIs, and energy payback times of electricity generating power plants (Energy 52 (2013), 210), and a report by Graham Palmer (Energy in Australia: Peak Oil, Solar Power, and Asia’s Economic Growth, Springer 2014), to support his conclusions. Summarizing his case, Professor Morgan writes:

It’s important to understand the nature of this EROEI limit. This is not a question of inadequate storage capacity – we can’t just buy or make more storage to make it work. It’s not a question of energy losses during charge and discharge, or the number of cycles a battery can deliver. We can’t look to new materials or technological advances, because the limits at the leading edge are those of earthmoving and civil engineering. The problem can’t be addressed through market support mechanisms, carbon pricing, or cost reductions. This is a fundamental energetic limit that will likely only shift if we find less materially intensive methods for dam construction.

UPDATE: A commenter on this thread has alerted me to an article by chemical engineer Vasilis Fthenakis, titled, How Long Does it Take for Photovoltaics Io Produce the Energy Used? (PE magazine, January/February 2012) claiming that “with a lifetime of 30 years, their ERRs [energy return ratios – VJT] are in the range 60:1 to 15:1. depending on the location and the technology, thus returning 15 to 60 times more energy than the energy they use.” If that were correct, then solar photovoltaic panels would be a viable source of energy. However, Fthenakis’ claim has been criticized as seriously flawed by energy researcher Graham Palmer in his online article, Energy in Australia (a precis of his 2014 book of the same title). Palmer concludes that the EREOI (energy returned on energy invested) for solar photovoltaics is no more than 3, which is far below the commercial viability threshold of 7 – and recently, another team of researchers (Prieto and Hall, 2013) independently reached the same conclusion as he did:

It is only recently that more rigour has been applied to trying to understand the figures, leading to Prieto and Hall’s (2013) examination of large-scale deployment of PV in Spain through 2009 and 2010. Coincidentally, I was researching a paper on PV, which was published in

Sustainability Journal and BNC shortly afterwards (Palmer 2013). Both of us came to similar conclusions on EROI (between 2 and 3), which is significantly less than commonly quoted figures, and below the critical minimum EROI required for society (Hall et al 2009). This led to an email exchange with energy and solar researchers, and the writing of this book (Palmer 2014) for the SpringerBriefs series.

A recent article by Palmer, titled, Solar PV – an irresistible disruptive technology? (May 8, 2014), highlights the flaws in Fthenakis’ calculations:

The critical issue of intermittency is ignored, the system boundary for PV panels is truncated to exclude upstream energy costs, and many other important system-based factors are deemed to lie beyond the standard boundaries.

Similarly, the often assumed idea that a “suite of renewables” with smart-grids and electric vehicles to achieve some sort of “optimized synergy” is frequently overstated. It is well established that geographical smoothing, along with “technology-diversity” smoothing can improve the statistical performance of integrated systems, but cannot deal with the “big gaps” events, particularly during winter.

Similarly, combining electric vehicles with solar PV seems like a great idea at face value, but how would it work at a system level? Will motorists want to “fill up their tank” during the middle of the day at peak tariffs, and sell back to the grid at night? How will the vehicle get recharged so it has full range by the morning? What happens to charging during winter?

Finally, Professor John Morgan’s review of Palmer’s 2014 book, Energy in Australia, makes the additional point that “adding storage to solar PV reduces the EROEI, to just above 2. This is not enough net energy to be a viable energy source.”

To sum up: claims that solar photovoltaic panels could yield a viable energy return on energy invested appear to be based on naive and badly flawed assumptions.

(END of Update.)

(b) As the market share of renewable energy sources increases, they’ll become more expensive and less economical

Second, as solar energy’s market share increases, it’ll actually become more expensive and less economical, making it commercially non-viable, according to a recent MIT report, titled, The Future of Solar, which is helpfully summarized in an article by Rhodes Scholar and physicist Dr. Varun Sivaram, titled, The World Needs Post-Silicon Solar Technologies. In his article, Sivaram points out that “solar panels face a moving target for achieving cost-competitiveness with fossil-fuel based power that becomes more difficult as more solar panels are installed. As a result, even after the expected cost reductions that accompany increased experience with silicon technology, solar PV cannot seriously challenge and replace fossil-fuel generation without advancing beyond the economics of silicon.” The MIT report paints a sobering picture. It states that unsubsidized silicon solar panels are not currently cost-competitive with conventional generation in the United States, and that as the penetration of solar power increases, solar will become less valuable. Nor is storage is not a magic bullet that will make silicon solar panels economically viable: storage does improve the economics of solar at high penetration, but not enough to stabilize the moving target for solar cost-competitiveness. The reports states that “beyond modest levels of penetration and absent substantial government support or a carbon policy that favors renewables, contemporary solar technologies remain too expensive for large-scale deployment,” although it adds that “[large] cost reductions may be achieved through the development of novel, inherently less costly PV technologies, some of which are now only in the research stage.” In short: new technologies are necessary for solar to successfully compete. The report identifies some promising candidates, but the take-home message is that solar energy isn’t going to replace fossil fuels anytime soon.

(c) Environmental damage caused by renewable energy sources

Finally, few people realize that solar energy causes massive environmental damage: the components of solar panels, which include several “conflict minerals,” are often mined in countries with weak health and safety regulations. Even worse, solar energy has to rely on batteries for energy storage, due to the intermittent nature of sunlight. Just one electric car battery contains 50 kilograms of graphite, an environmental pollutant which is wreaking havoc in China, according to a report by by Konrad Yakabuski in The Globe and Mail (May 27, 2015), titled, The darker side of solar power. (The latter problem would also apply to wind energy.) Finally, we should recall that the indoor air pollution generated by biomass kills 3 million people every year.

There’s no way to solve these three problems any time soon: greater reliance on nuclear energy will be absolutely vital, if we want to reduce man-made greenhouse gas emissions to zero within the new 50 years.

A journalist punctures the media hype about solar energy

Despite these weighty problems with solar energy, the media continues to trumpet every new advance as if it were the magic solution to the problem of global warming. Thankfully, not all journalists are so gullible. A recent article by Will Boisvert in The Breakthrough (May 18, 2015) The Grid Will Not Be Disrupted: Why Tesla’s Powerwall Won’t Catalyze a Solar Revolution cites figures which puncture the media myth that advances in battery technology will soon render solar power viable on a large scale:

The announcement two weeks ago of Tesla Motors’ cheap new lithium-ion storage batteries set the renewable energy world on its ear. Breathless commentators pronounced them a revolutionary advance heralding cheap, ubiquitous electricity storage that would make solar power a 24/7-power source for the masses. Elon Musk, Tesla’s wunderkind CEO, fed these hopes at the glitzy product launch for the 10 kilowatt-hour (KWh) Powerwall home storage battery…

Powerwalls would let developing countries “leapfrog” straight to a solar-plus-storage electricity system, he explained, and the 100-kWh utility-scale Powerpack version would have a world-historical effect…

…Can batteries transform intermittent wind and solar power into reliable energy sources for a comprehensive decarbonization of the grid? Will billions of Powerpacks transition the world to an all-renewable energy supply? The answer, unfortunately, is no…

Consider the 160 million Powerpacks that Musk thinks would transition the US grid to solar and wind, a total of 16 terawatt-hours (trillion watt-hours) of storage. That’s several quantum leaps in storage capacity — but still only a drop in the nation’s gargantuan electricity bucket. America used about 4,100 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity last year, so those Powerpacks would be able to backstop a hypothetical all-intermittents American electricity supply for all of 34 hours. (That’s assuming average weather; during a heat wave or cold snap electricity demand would be much higher and the batteries might drain much faster.) The price of the Powerpacks by themselves, installation not included, would be $4 trillion. Want to extend that to two days’ worth of battery power? Throw another $1.6 trillion on the fire.

Renewables can’t solve the problem of rising coal emissions in India

Even if solar energy were to take off in Western countries, it will do very little to alter the situation in India, where despite a burgeoning local solar industry, coal use is projected to increase by 2.5 to 3 times by the year 2030, according to a recent IPCC report. “Even with the most aggressive strategy on nuclear, wind, hydro and solar, coal will still provide 55% of electricity consumption by 2030,” declares Jairam Ramesh, who led the Indian delegation at the 2009 climate conference in Copenhagen. In a recent article (The Guardian, 16 April 2015), former vice-president Al Gore points out the harmful effects of coal on human life expectancy in India and China: “Air pollution is already reducing life expectancy in northern China by five and a half years, and in India (whose capital, New Delhi, has the worst air pollution of any large city in the world) by 3.2 years.” But one-third of Indians still have no access to electricity, and there is near-unanimity across a broad swath of Indian politicians that India must be allowed to burn more coal, in order to become an industralized country. Opposition to emissions caps is almost universal, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi openly speaks of India’s “right to growth.”

To give credit where credit is due, I should mention that Prime Minister Modi’s government has quintupled the 2022 targets which were set for non-fossil energy by the previous regime, to 175 GigaWatts – almost six times its current level. If the target is met, that would give India more than twice as much solar power as the United States. Ratul Puri, chairman of Hindustan Powerprojects Ltd, a very large corporation which has invested heavily in both coal and solar,believes that 15 to 20% of India’s energy could come from solar power in the near future. But Indian entrepreneur Kushagara Nandan, who runs Sunsource Energy, a solar start-up, cautions: “Unrealistic expectations must not be raised. It’s crucial to realise that solar must be part of the mix – it cannot substitute for other sources. For the foreseeable future, India doesn’t have a choice between coal and solar. It needs both.”

What about other renewable energy sources – hydroelectricity, wave power, geothermal, biofuels and wind?

So far, I have mainly discussed solar energy. But other renewable sources of energy face even greater problems. In a blog article titled, Fossil fuels are not finished, not obsolete, not a bad thing (March 22, 2015), Dr. Matt Ridley, former science editor of The Economist, explains what’s wrong with other renewable energy sources (hydroelectric, wave power, geothermal energy, biofuels and wind power):

As for renewable energy, hydroelectric is the biggest and cheapest supplier, but it has the least capacity for expansion. Technologies that tap the energy of waves and tides remain unaffordable and impractical, and most experts think that this won’t change in a hurry. Geothermal is a minor player for now. And bioenergy — that is, wood, ethanol made from corn or sugar cane, or diesel made from palm oil—is proving an ecological disaster: It encourages deforestation and food-price hikes that cause devastation among the world’s poor, and per unit of energy produced, it creates even more carbon dioxide than coal…

The two fundamental problems that renewables face are that they take up too much space and produce too little energy…

To run the U.S. economy entirely on wind would require a wind farm the size of Texas, California and New Mexico combined—backed up by gas on windless days. To power it on wood would require a forest covering two-thirds of the U.S., heavily and continually harvested.

Sounds like a plan? Why the widely-hyped Jacobson plan for 100% renewable energy won’t work

A recent article by David Roberts which was featured on RealClearEnergy.org highlighted a plan by Stanford researcher Mark Jacobson, which claimed that the US economy could be run entirely on renewable energy by 2050. Here’s how Roberts summarized the plan in his article (Here’s what it would take for the U.S. to run on 100% renewable energy, Vox.com, updated June 9, 2015):

It is technically and economically feasible to run the US economy entirely on renewable energy, and to do so by 2050. That is the conclusion of a new study in the journal Energy & Environmental Science, authored by Stanford scholar Mark Z. Jacobson and nine colleagues.

Jacobson is well-known for his ambitious and controversial work on renewable energy. In 2001 he published, with Mark A. Delucchi, a two-part paper (one, two) on “providing all global energy with wind, water, and solar power.” In 2013 he published a feasibility study on moving New York state entirely to renewables, and in 2014 he created a road map for California to do the same.

His team’s new paper contains 50 such road maps, one for every state, with detailed modeling on how to get to a US energy system entirely powered by wind, water, and solar (WWS). That means no oil and coal. It also means no natural gas, no nuclear power, no carbon capture and sequestration, and no biofuels.

The road maps show how 80 to 85 percent of existing energy could be replaced by wind, water, and solar by 2030, with 100 percent by 2050…

No one can say any longer, at least not without argument, that moving the US quickly and entirely to renewables is impossible. Here is a way to do it, mapped out in some detail. But it is extremely ambitious…

The core of the plan is to electrify everything, including sectors that currently run partially or entirely on liquid fossil fuels. That means shifting transportation, heating/cooling, and industry to run on electric power…

Jacobson and colleagues … say that the grid they propose will be not only reliable, but more reliable than today’s grid.

If your reaction upon reading these headlines was, “Sounds too good to be true,” then you’d be right. Unfortunately, Jacobson’s latest study is behind a paywall. But as David Roberts noted in his review, it’s actually a collection of 50 road maps – one for every state of America. Back in 2013, Jacobson announced plans for the full-scale conversion of the state of New York to wind, water and solar [WWS] technology. Jacobson’s plans were widely panned, and a devastating review of them was published in an article titled, Critique of the 100% Renewable Energy for New York Plan (The Energy Collective, November 17, 2013) by energy and technology writer Edward Dodge, which I’d like to quote from here, as it conveys the flavor of what is wrong with Jacobson’s modeling:

I feel compelled to respond to a paper that is widely referenced by anti-hydrofracking activists as proof that New York can move beyond fossil fuels and power 100% of its energy needs with renewables. The WWS (Wind, Water and Solar) Plan for New York (Jacobson et al., 2013) is part of a series of papers authored chiefly by Prof Mark Jacobson from Stanford University that can be found here. The New York paper includes contributions from Cornell University professors Bob Howarth and Tony Ingraffea. Jacobson attempts to makes the case that society can acquire all of the energy it needs for all purposes in a relatively short period of time from a combination of solar, wind, hydro and geothermal. Jacobson is opposed to nuclear power and also opposes all hydrocarbon fuels whether bio or fossil based because of the contention that all CO2 emissions must be eliminated in order to prevent a catastrophic melting of the arctic sea ice. The plan calls for an 80% conversion to WWS [wind, water and solar] by 2030 and 100% conversion by 2050. Unfortunately the plans are deeply flawed from a practical and technical perspective.

Jacobson makes broad assumptions about the suitability of many different technologies and offers little evidence to back up his claims. Such assumptions include the complete abandonment of hydrocarbon fuels for vehicles, heavy equipment, ships and planes and conversion to battery and hydrogen fuels. No proof is offered that these new technologies can meet the performance requirements of existing machines. Nor are any references from industry or the military presented to justify the technical feasibility of the claims. Jacobson contends that some electric and fuel cell vehicles have come to market but that hardly meets the burden of proof that a century and a half of performance based industrial development can be converted over wholesale to new equipment that is not currently proven in real world use.

A common flaw in the WWS model is the use of unproven technologies along with insufficient analysis of their land use impacts. For example, wave devices, tidal turbines and geothermal are included even though they are not mature technologies. The WWS plan has virtually no discussion of the land use impacts of new power transmission or discussion of hydrogen storage and distribution. Other writers have disputed Jacobson’s assumptions about electricity storage and economics here and here. Debate over the feasibility of intermittent power sources to keep the grid running can be found here and here, a response to the critics by Jacobson can be found here….

The most glaring defect in the entire model is the use of CSP, concentrated solar power, which is a thermal technology used in the desert and not applicable to New York. I would challenge the authors to find any qualified engineers or developers who would certify these types of facilities for NY. The authors call for 387 CSP plants rated at 100 MW each to be built throughout the state. Each 100 MW CSP plant requires roughly 1 square mile of flat, unburdened land and requires the highest levels of solar insolation. New York has the opposite characteristics: long, cold, dark winters and rolling hills covered in forests, fields and farms. By the authors’ own figures, 327.3 square miles of land would have to be cleared to construct 387 of these projects across the state…

The wind model presented is troubling because it assumes to utilize as many wind turbines as conceivably possible, basically placing turbines on every single hill with decent wind in the state without regard to people already living there. Similar to the trick in the PV [photovoltaic] model, the authors choose particularly large turbines that allow them to overstate production…

The numbers presented for offshore wind are truly astounding. 12,700 turbines at 5 MW each for a total capacity of 63,550 MW. The authors do fairly note that there is not a single off shore wind farm anywhere in the United States in 2013, but that does not stop them from asserting that some of the busiest multiuse waterways will be packed to the maximum extent with a forest of very large turbines. The available waterways in NY are the coasts of Long Island and parts of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. There is no discussion of impacts on shipping lanes, boating, fisheries, recreation or general public acceptance. No discussion of bathymetric properties of the sea floor and whether the farms of the proposed scale are even technically possible.

I hate to be critical of proposals for wind and solar because I hope these industries continue to grow, but the WWS plan lacks any technical credibility whatsoever. It has been widely criticized by many writers and for good reason. I only chose to add to the pile because I see the paper being hailed for political purposes by those with an agenda opposing drilling for natural gas. Mark Jacobson has been making appearances on television claiming this is all technically feasible, well I have to disagree.

I don’t want to sound uncharitable here. To give credit where credit is due, Jacobson has produced a very detailed plan for the conversion of the entire planet to renewable sources of energy – and he’s had the honesty to put a price tag on his plan: $100 trillion, which he thinks is affordable. And if I had to pick a plan for converting the world to renewable energy sourves, I’d pick Jacobson’s: it’s much better than anything else I’ve seen. I’ll be discussing the economic implications of his plan below, in section 4. But for the time being, let me note that while it contains some very detailed estimates of the requirements for a conversion to renewable energy, it appears to be wildly impractical on many counts: as the review cited above points out, Jacobson’s treatment of the issues lacks depth. Finally, as far as I am aware, Jacobson does not address the three fundamental problems I discussed earlier, in connection with renewable sources of energy. Summing up, I would have to say that Jacobson’s plan, while commendably ambitious, needs a lot more work.

Fossil fuels will be here for at least a few decades

Many readers may think that if we actually had a viable plan for a conversion of the planet to renewable sources of energy, our problems would be solved. Unfortunately, fossil fuels won’t go away in a hurry. A recent report by Kurt Cobb in Oilprice.com points out that “[v]ery little of the existing electricity generation infrastructure is coming down soon,” and concludes that “far from replacing existing fossil fuel generating plants, renewables are simply going to add to total electricity generation as demand grows.” In his article, Cobb also notes that governments worldwide currently pay out $550 billion in subsidies each year – that’s the figure for 2013 – on the production of oil, coal, and natural gas, which is more than four times the subsidies for renewables including wind, solar and biomass. But instead of spending $550 billion on renewable energy research, Cobb argues that a much better use of that money would be spending it on known technologies that drastically reduce our consumption of energy – for instance, passive house technology, which can reduce building heating and cooling energy use by 80 to 90 percent. That would be a better investment. Cobb also recommends a high and rising carbon tax, to accelerate the energy transition away from fossil fuels.

The IMF’s latest myth: governments subsidize fossil fuels by $5.3 trillion a year, worldwide. The true figure is one-tenth of that

By the way, Brad Plumer of Vox.com has written an excellent rebuttal of the recent claim made by the IMF that we spend $5.3 trillion a year on fossil fuel subsidies. Plumer explains that the IMF is using a highly idiosyncratic definition of “fossil fuel subsidy” in its report: for most people, the term refers to government under-writing of the production and/or consumption of coal, oil or gas. Defined in this way, government fossil fuel subsidies total around $500 billion per year, worldwide. But the IMF’s definition of a subsidy includes not only government assistance but also the costs of any environmental damage caused by coal, oil and gas each year, which is not borne by consumers. Economists refer to these costs as externalities. What the IMF is really saying is that governments should be taxing coal, oil and gas a whole lot more, to cover the environmental costs of global warming, which are inflicted on society as a whole. The IMF would like governments to tax fossil fuels by an additional $5.3 trillion a year. That may or may not be a good idea, but a failure to impose a tax is not the same thing as a subsidy.

Additionally, the IMF’s definition of environmental damage caused by global warming is extraordinarily broad: it even covers car accidents, traffic fatalities and congestion, all of which are caused not by gasoline per se but by automobiles. In his essay, Brad Plumer points out that if we switched over to solar-powered electric cars tomorrow, we’d still have traffic accidents, fatalities and congestion. So where is the sense in blaming gasoline for that?

Dr. Matt Ridley has more to say about fossil fuel subsidies in his blog article, Fossil fuels are not finished, not obsolete, not a bad thing (March 22, 2015), where he points out that renewables are currently subsidized to the tune of $10 per gigajoule, and that this kind of subsidy tends to transfer money from the poor to the rich – especially landowners, who are paid to install wind and solar power facilities on their property. On a per-gigajoule basis, fossil fuel subsidies are much lower in magnitude, and tend to benefit the poor:

It is true that some countries subsidize the use of fossil fuels, but they do so at a much lower rate—the world average is about $1.20 per gigajoule — and these are mostly subsidies for consumers (not producers), so they tend to help the poor, for whom energy costs are a disproportionate share of spending.

Finally, most people are unaware that these fossil fuel subsidies are not paid by Western countries, but by countries like Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India and China, to their own citizens and/or local industries, as this chart shows. There’s little that Western governments can do about ending these subsidies.

Energy transitions take time

Finally, a recent article in Politico by energy visionary Vaclav Smil — Bill Gates’s favorite author — titled, Revolution? More like a crawl, explains that transitions in energy use are subject to time constraints that not even brilliant innovators are capable of overcoming:

Google launched its “Clean Energy 2030″ in October 2008, aiming to eliminate U.S. use of coal and oil for electricity generation by 2030, and cut oil use for cars by 44 percent. It was completely abandoned in November 2011.

Elon Musk, the entrepreneur some U.S. media have proclaimed to be a man more inventive than Edison, makes much-praised electric cars — but Tesla ended 2014 with another loss after selling only 17,300 vehicles in a market of 16.5 million units, claiming a share of 0.1 percent of the U.S. car market.

Summary

I’d like to conclude by quoting from a powerfully worded article titled, Baby Lauren and the Kool-Aid (July 30, 2011) by Professor James Hansen, former Vice-President Al Gore’s climate adviser:

Can renewable energies provide all of society’s energy needs in the foreseeable future? It is conceivable in a few places, such as New Zealand and Norway. But suggesting that renewables will let us phase rapidly off fossil fuels in the United States, China, India, or the world as a whole is almost the equivalent of believing in the Easter Bunny and Tooth Fairy.

4. The true cost of fighting global warming has been scandalously under-stated by politicians

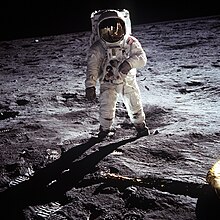

|

Image of Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon on the Apollo 11 mission. The Apollo program cost $110 billion altogether, in today’s dollars. Fighting global warming could cost 1,000 times more than that. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Politicians have a habit of telling their constituents what they want to hear. The public desperately wants to believe that the problem of global warming has an affordable solution. However, the truth is that we don’t know how much it will cost to fight global warming. A realistic estimate, factoring in the political and technological uncertainties, would be: at least $100 trillion, and maybe considerably more. However, most people have no inkling of the real cost of combating global warming. No-one has ever told them the truth.

A flawed estimate by the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate Change

In 2014, a report by the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate Change, chaired by former Mexican President Felipe Calderon and advised by Lord Stern, former UK government economist, declared that the cost of tackling climate change was very modest: clean technology could be achieved by adding just 5% to the $6 trillion a year spent on power and transport projects. The total cost would amount to just $4 trillion, over the next 15 years. But critics, including Professor Gordon Hughes, an energy economist at Edinburgh University, responded that the report’s conclusions are over-optimistic, adding that the total costs of renewables to energy systems as a whole were greater than they appeared.

Sam Bliss, in an article in Grist titled, No, economic growth and climate stability do not go hand in hand (September 30, 2014) accuses the authors of the report of deliberately painting an overly rosy picture, designed to reassure politicians and investors that the world economy can continue to grow, even as it cuts greenhouse gas emissions. Bliss contends that the report has skirted the vital question: can we grow economically while we achieve climate stability? Bliss is doubtful: he cites estimates by Kevin Anderson of the Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research that rich countries would have to cut their carbon emissions by 10 per cent a year in order to stay under the “danger threshold” of 2 degrees Celsius, and at the same time avoid imposing a disproportionate share of the burden of cutting emissions on poor countries (whose ecological footprint is far smaller than that of affluent countries). No country, argues Bliss, can cut its emissions by 10 per cent a year and grow at the same time.

A better estimate: stopping global warming will cost the world $44 trillion – if we’re very, very lucky

The total cost of fighting global warming has been more realistically estimated in a 2014 report by the International Energy Agency, at $44 trillion. That’s what government and investors need to invest in clean energy and related technologies from 2011 to 2050 in order to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Such an outlay will require spending of $1 trillion a year, or about 1.3 percent of the world’s annual output of goods and services, or about $140 a person. In reality, however, it will be the developed and middle-income countries (N. America, the EU, China, Japan and Australia & New Zealand) that foot the bill, and for these countries, $1 trillion would represent about 2% of their annual GDP.

In any case, the IEA’s estimate that fighting global warming will cost $44 trillion is based on an ideal scenario. That scenario tell us what it will cost to switch away from fossil fuels, if we all act now and make intelligent decisions, and if technologies work out the way we hope they will. And if technology for capturing and storing carbon dioxide can’t be deployed, the cost of stabilizing greenhouse-gas levels will more than double, according to a recent IPCC report. That would mean that developed and middle-income countries end up spending 4% of their annual GDP on fighting global warming.

The 2014 report by International Energy Agency also claimed that although a global transition to clean energy would cost $44 trillion, it would save $115 trillion in avoided fuel, thereby resulting in a net “saving” of $71 trillion. But as we’ve seen, the $44 trillion figure is based on an ideal scenario, and the true cost of a transition to clean energy may be more than twice as much. In that case, most or all of the $71 trillion will disappear. And I might add that a $71 trillion reduction in economic activity through fuel savings will mean job losses, a reduction in tax revenues for the government, and a lower value of many companies’ stocks – all of which can hamper economic growth.

The true price of stopping global warming is more likely to be $100 trillion

In November 2009, Mark Z. Jacobson, at the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Stanford University, and Mark A. Delucchi, at the Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California at Davis, wrote an article (“A Path to Sustainable Energy by 2030”, Scientific American 301, 58 – 65, 2009) which discussed what was needed in order to reduce fossil fuel emissions to zero, worldwide, and in 2011, they provided detailed supporting calculations here and here. Daily Kos journalist N. B. Books has written an excellent summary of their article here. The authors of the 2009 study estimated that eliminating fossil fuels worldwide would require the construction of 1.7 billion 3-kilo-Watt rooftop photvoltaic (PV) systems, 3.8 million 5-Mega-Watt wind turbines, 720,000 0.75-Mega-Watt wave devices, 490,000 1-Mega-Watt tidal turbines, 49,000 300-Mega-Watt concentrated solar plants, 40,000 300-Mega-Watt solar power plants, 5,350 100-Mega-Watt geothermal power plants, and 270 new 1,300-Mega-Watt hydroelectric power plants. And the cost? $100 trillion, over 20 years, not including transmission. The authors insist that this gigantic sum “is not money handed out by governments or consumers”; rather, it is “investment that is paid back through the sale of electricity and energy.” My question is: investment by whom? Even Bill Gates’ net worth is “only” $79.1 billion. That’s 1,250 times less than the amount required. The authors of the study also argue that relying on traditional power sources would require $10 trillion to cover the costs of the extra thermal plants that would need to be built over the next two decades, “not to mention tens of trillions of dollars more in health, environmental and security costs.” But spending money on more power plants and paying taxes and fines to cover the costs of fossil fuel emissions are very different kinds of business activities from investing $100 trillion in a huge worldwide project to switch the entire planet to new sources of energy. That kind of activity requires massive government investment, and to suppose it could be done without that investment is nothing more than a pipe-dream.

Daily Kos writer N. B. Books (whose real name is Tony Wikrent) is also unfazed about spending $100 trillion to stop global warming. He writes: “We can just create the money needed out of thin air. That is, in fact, the way money has always been created.” The author’s left-wing bias is clearly showing here, and he appears unaware that many economists have panned the idea (advanced by some liberals) of printing trillion-dollar coins to pay off America’s public debt, on the grounds that it would create a crisis of international confidence in the American economy. But at least these coins would have no impact on inflation, as they would be sitting in a Treasury vault. However, if America or any other country were to create $100 trillion to pay for the cost of fighting global warming, that money would have to enter circulation – and its impact would be inflationary. Books also writes that “just a ten percent increase in world output” from $71 trillion (the world’s current GDP) to $78 trillion, paid over 15 years, would cover the costs. How the author thinks the world can magically increase its GDP by 10% overnight is a mystery to me.

The cost of fighting global warming may prove to be incalculable

Finally, Robert Pindyck, a professor of economics and finance at MIT, candidly admits that we can’t really calculate the true costs of combating global warming: “All we can do is speculate. We don’t really know the costs. We don’t really know the benefits.”

A failure to distinguish two very different questions about cost

When I survey the arguments put forward by both sides about the cost of fighting global warming, I am struck by a failure to distinguish two very different questions relating to cost. The first question is: do the benefits of fighting global warming exceed the costs? This is a question about the long-term, and I think a good economic case could be made that they do, if we accept that there’s a significant chance that global warming could eventually raise temperatures to more than 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels – even if we rate this chance as rather low (say, 10 or 20%). The Stern Review of 2006, which attracted a storm of controversy (about which see here and here, certainly made a very powerful case, on purely economic grounds, that the benefits of fighting global warming do indeed exceed the costs.

The second question asks for a “meat-and-potatoes” calculation of revenues and expenses: what are the net expenses incurred by countries around the world in fighting global warming, and can governments afford to pay for these expenses? Whereas the first question looks at benefits and costs (which may relate to the environment as a whole), the second question focuses exclusively on governments’ annual budgets.

The point I wish to make here is that a “yes” answer to the first question does not imply a “yes” answer to the second. The social and environmental benefits of combating global warming may well exceed the costs, but at the same time, the budget expenses incurred by the world’s governments in fighting global warming may prove to be unaffordable.

What readers need to understand is that we can only proceed with plans to end global warming if the answer to the second question is “yes.” If the answer is “no,” then we’re sunk, no matter how great the benefits of ending global warming prove to be. That is why the question of the dollar cost of fighting global warming is so important.

What will be the impact on the world’s GDP? We don’t know.

Finally, an oft-cited IPCC estimate that fighting global warming will shave a mere 0.06% off GDP growth is pure poppycock. As David Roberts convincingly argues over at Grist, we do not, and cannot, know how much it will cost to tackle climate change. Roberts cites three academic papers to support his arguments – a 2015 report by Richard Rosen of the Tellus Institute and Edeltraud Guenther of the Technische Universitaet Dresden, an earlier report by Frank Ackerman (Stockholm Environment Institute-US Center, Tufts University) and his colleagues, and a 2013 report by Serban Scrieciu, Terry Barker and Frank Ackerman. In their 2015 report, Rosen and Guenther conclude that “not only do we not know the approximate magnitude of the net benefits or costs of mitigating climate change to any specific level of future global temperature increase over the next 50–100 years, but we also cannot even claim to know the sign of the mitigation impacts on GWP, or national GDPs, or any other economic metric commonly computed.” The authors recommend that “the IPCC and other scientific bodies should no longer report attempts at calculating the net economic impacts of mitigating climate change to the public in their reports.”

Could relacing fossil fuels with nuclear power and/or renewable energy actually boost countries’ GDP, as some economists contend? Possibly – and possibly not. The truth is that we really don’t know. The point I’d like to make, however, is that the fight against global warming will cost a heck of a lot of money (around $100 trillion), and at the present time, scientists and economists cannot guarantee that we’ll have enough money to stop global warming, within the time available. It may prove to be financially impossible. We just don’t know.

5. Why the Millennium Development Goals must be met, come what may

|

Child next to an open sewer in a slum in Kampala, Uganda, at risk of diarrhea and stunted growth. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In a world where 2.5 billion people do not have basic sanitation, where 1 in 9 people remain hungry, where 6 million children die before their fifth birthday every year, and where only half of all women in developing countries receive adequate maternal care, it is absolutely vital that the countries of the world do their utmost to meet the United Nations Millennium Development Goals and the more ambitious post-2015 development agenda. (For more information on the Millennium Development Goals, see here.)

The world currently spends almost $135 billion per annum on overseas aid. That’s a commitment we must continue to keep, no matter how serious the global warming crisis gets. For even if the direst prognostications of the IPCC forecasters turn out to be correct, it would be morally wrong to withhold money from children who are dying now, in order to save generations of as-yet-unconceived children. Starvation, malnutrition and disease are clear and present dangers which kill millions. Future dangers can never take precedence over these crises.

The world currently faces a number of looming crises: (a) the problem of billions of people living in poverty, with millions of these people dying every year from malnutrition, disease and indoor air pollution; (b) the aging society in both Western and former Communist countries, and the danger that governments in many countries may run out of money to fund Social security payments; (c) the danger of full-scale war breaking out in the Middle East; (d) the danger of a military showdown with China in the South Pacific; (d) the international refugee crisis, as millions flee their countries in search of a job and political stability; and (e) the real risk of another global pandemic.

My concern is that if we add (f) the $100 trillion cost of ending global warming, to the list, we’re no longer going to be able to address all of the other problems. It would surely be a political miracle – arguably the greatest in human history – if we managed to resolve or avert all of these problems (Third World poverty. the aging crisis, war in the Middle East, war between China and the U.S., refugees, and the threat of a pandemic), and at the same time, we managed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to ZERO by 2070. Frankly, I simply don’t believe it’s possible. My gut tells me that something’s got to give.

6. How much can we really trust the IPCC’s global warming predictions?

Until now, I have assumed that the IPCC’s global warming predictions for the 21st century are reliable and accurately represent the state of current scientific knowledge. But while it’s true that the vast majority of climatologists would agree that global warming is real and largely man-made, there is far less agreement among scientists regarding whether global warming will be dangerous or not, during the nest few decades.

KEY POINTS: 1. People have swallowed a lot of myths about global warming, thanks to media hype: for example, the myth that it is causing extreme weather (true for heat waves; not true for hurricanes, tornadoes, floods or droughts), or that sea levels are rising rapidly as a result of global warming (actual rate: about 2 feet a century), or that global warming is already causing mass extinctions (at most, only a few species have died out due to global warming), or that global warming is causing hundreds of thousands of deaths a year (it may be doing so, but it is also precenting a much greater number of deaths in other countries). 2. The term “denialist” is a totally inaccurate way to characterize global warming skeptics. Most of them are lukewarmers, like Dr. Matt Ridley, who was once a global warming believer but who came to believe, after careful study, that global warming, while real, wasn’t anything like as dangerous as generally believed. Lukewarmers tend to believe that a doubling of carbon dioxide levels will lead to an average global temperature rise of 1.6 degrees above pre-industrial levels, while global warming alarmists propose figures of around 3 or 4 degrees. 3. So far, the models tend to support the alarmists – but if we look st the actual temperature data of the last 40 years, it tends to support the lukewarmers. If they are right, then we don’t have to hit the panic buttton right away: we have a few more decades to address the problem of global warming in a calm, rational manner. |

Hosing down the myths

The public perception of the global warming debate has been influenced by several widely propagated myths and half-truths, which, if exposed, would cause most people to question the current scientific consensus.