|

In my previous post, I focused on the anti-religious slant of Professor Steve Pinker’s best-selling book, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Viking Adult, 2011). In this post, I’d like to critique Pinker’s methodology, his misuse of statistics, and his faulty figures relating to atrocities perpetrated in the past.

What Pinker gets right, and what he gets wrong

Pinker’s book deserves to be commended for its methodological fairness, in its approach to the historical data relating to violence. Datasets relating to violence are included in their entirety, with no cherry-picking of the historical data. So far, so good.

Pinker is right to focus on percentages, rather than absolute numbers, in evaluating the level of violence in various societies throughout history. Unfortunately, he seems to have problems in extracting these percentages from the historical data he presents. The two relevant percentages in assessing the level of violence in a given time period are:

(a) the percentage of deaths in that period that can be attributed to acts of violence; and

(b) the percentage of people that died each year, as a result of violence.

It turns out that if we include all wars, atrocities and acts of murder, then the percentage of deaths that can be attributed to known acts of violence is highest for the 20th century. If, on the other hand, we look at the percentage of people that died each year as a result of violence, then you could argue (using Pinker’s figures, which as I’ll show are badly flawed) the 13th and 17th centuries were more violent than the 20th, but even so, you’d still have to concede that the 20th century was still one of the most violent of the past 25 centuries in human history.

Looking at the historical data from 500 B.C. to the present, it would be utterly wrong to claim, as Pinker does, that the level of violence has generally been declining over time. As I’ll argue below, only when viewed in relation to the murderous violence pervading prehistoric societies and (more controversially) stateless tribal societies, does 20th century civilization look relatively peaceful in comparison. But all this shows is that the State plays an important role in reducing violence. What it doesn’t establish is Pinker’s rosy Whiggish thesis that we’re getting better at handling conflicts, over the course of time.

A crude method of comparing the level of violence of two different eras: compare the relative magnitudes of the worst war or atrocity in each era

As a very crude first approximation, if you were trying to compare the relative violence of two centuries – say, the eighth and the nineteenth centuries – you might want to compare the percentages of people killed in the worst massacre occurring in each century, providing that the two massacres took place over a roughly similar time period. To help readers make this comparison, I recommend that they have a look at The New York Times (6 November 2011) chart of wars and atrocities over the last 2,500 years, prepared by Bill Marsh and based on Matthew White’s best-seller, The Great Big Book of Horrible Things. This chart provides non-specialist readers with an excellent sense of historical perspective.

Thus if you compare the An Lushan rebellion, which (according to Pinker’s faulty figures) killed about 6% of the human race in the eighth century’s worst atrocity and lasted for eight years (755-763), with the nineteenth century’s worst atrocity, the Taiping Rebellion, which killed less than 2% of humanity and lasted for 14 years (1850-1864), then you might tentatively conclude that the nineteenth century was probably more peaceful than the eighth – at least, for people living in China (where both atrocities occurred). It would be unwise to draw any conclusions about Europe or Africa from those figures, of course – and even in China, your conclusion might be wrong, because a steady stream of medium-sized atrocities spanning several decades in one century can kill more people than a single large-scale atrocity occurring in that century.

We can use the crude method I described above to address the question of whether humanity is becoming less violent over time, as Professor Pinker claims. The short answer is: that depends on how far back in time you want to go, and how fine-grained your chronological comparisons are. Looking at the percentages of people killed in the worst acts of violence, it would seem that the world was a less violent place in the 20th century than it was during the 13th century. But what happens if we compare the level of violence in the 13th century with that of the 1st century A.D.? According to the New York Times chart of atrocities based on Matthew White’s research, around 5.9% of the human race was killed in the Red Eyebrows revolt during the Xin dynasty (9-24 A.D.), in first-century China. That’s less than the 11.1% of the human race that (according to Pinker) was butchered by Genghis Khan (pictured above, courtesy of Wikipedia)over a comparable period in the 13th century (1206-1227 A.D.), so does that make the 1st century A.D. less violent than the 13th? Also, the bloodiest event of the 20th century (World War II) killed a higher percentage of humanity (2.6%) than the bloodiest event of the 19th (the Taiping Rebellion, which killed 1.7% of humanity over 14 years). Does that make the 19th century more peaceful than the 20th?

I should add that both the figures for the number of victims killed in the Red Eyebrows revolt and by Genghis Khan are highly inflated. Charles Phillips and Alan Axelrod, in their article, ‘Red Eyebrow’ Rebellion in the Encyclopedia of Wars, vol. 2 (New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2005) list the number of men under arms as “Unknown” and the number of casualties as “Unknown.” To complicate matters, the rebellion itself was triggered by two massive floods of the Yellow River, which resulted in the deaths of thousands and the subsequent starving of millions who were now homeless. To lay this at the door of human violence seems to me to be putting the cart before the horse. As for the Mongols: Pinker credits them with killing 40 million people, or 9% of humanity, but amateur historian Humphrey Clarke, in a critical essay entitled, How bad were the Mongols?, concludes that in all likelihood, “the Mongol Conquests killed 2.5% of the world’s population (450 million) in over a hundred years – from the 1230s to the late 14th century,” or about 11 to 15 million people altogether – which places them well below 20th century killing levels, in percentage terms.

The big picture: if anything, violence has been getting worse over the past 2,500 years

I would now invite readers to have a look at this graph (based on research conducted by the atrocitologist Matthew White, an authority frequently cited by Pinker in his book) depicting the 100 worst wars and atrocities, in percentage terms, from 500 B.C. to 2000 A.D. Indeed, Professor Pinker uses this very slide in his online talk, A History of Violence (27 September 2011). Strangely, there’s no sign of Pinker’s alleged “decline over time” in levels of violence. If we confine ourselves to the 18 wars and atrocities that killed more than 1% of the human race (i.e. where the death rate was 1,000 deaths per 100,000 people), we see that they break down over 500-year periods as follows:

500 B.C to 1 B.C.: 1 event

1 A.D. to 500 A.D. 3 events

501 A.D. to 1000 A.D. 1 event

1001 A.D. to 1500 A.D. 5 events

1501 A.D. to 2000 A.D. 8 events (2 occurring in the 20th century)

What! There were eight violent events that killed off more than 1% of the human race in the last 500 years, and two of these occurred in the last 100 years? That hardly inspires confidence in human progress, does it?

What about the funnel?

Readers might have noticed that most of the smaller-scale atrocities in the graph took place during the last two or three hundred years. But as Pinker himself acknowledges in his talk, A History of Violence (27 September 2011), that means nothing: the funnel in the graph in recent centuries is merely “an artifact of ‘historical myopia’: the closer you get to the present, the more information you have“. In any case, as we’ve seen, there have been lots of large-scale atrocities in recent centuries as well.

Pinker’s own authorities don’t agree with him!

More embarrassingly for Pinker, neither of the two atrocitologists whom he cites most frequently supports his claim that violence has been declining over time. Atrocitologist Matthew White is the author of a recent bestseller, The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History’s 100 Worst Atrocities (W. W. Norton, 2011). Pinker wrote a ringing foreword to the book, praising White for compiling “the most comprehensive, disinterested and statistically nuanced estimates available” of deaths from atrocities down the ages. How odd it is, then, to find that White flatly contradicts Pinker’s central thesis. On his FAQ page, White maintains that “the numbers fluctuate randomly over time, and we fight wars and oppress the weak because that’s what we’re good at.” “Fluctuate randomly” certainly doesn’t sound like a decline to me.

To make matters worse, Professor Rummel, the other leading atrocitologist cited by Pinker on his FAQ page, doesn’t support Pinker’s claim that there has been a long-term decline in violence over time, either. Professor Rummel declares on his Democratic Peace Q & A Web page (February 20, 2005) that “the 20th C[entury] was by far the bloodiest in history both in total murdered and as a proportion of the world’s population,” although he also maintains that violence has been dramatically declining worldwide since the 1980s: although he firmly maintains that violence has been dramatically declining worldwide since the 1980s. Three decades, however, is an historical eyeblink, and it would be ludicrous to call it an historical trend.

This is a rather embarrassing predicament for Pinker. His entire book is one long argument designed to show how, and why, violence has been declining over time, but his two leading sources for information on historical atrocities both reject the thesis that violence has declined over time. One wonders why Pinker would rely so heavily on sources that undermine his central thesis.

The fundamental problem with Pinker’s statistical methodology when comparing violence in different eras

Since the claim that the overall level of violence occurring in human societies is declining over time is a vital part of Professor Pinker’s thesis, we need to examine whether Pinker has a sound methodology for comparing the level of violence of different historical periods. My own research suggests that his methodology is somewhat flawed.

At the beginning of this post, I endorsed Professor Pinker’s contention that percentages are a much better way of comparing the level of violence in two different eras than absolute figures: after all, if you were thinking of moving to another country and you were wondering whether it was safe or not, you’d look at the homicide rate, not the total number of deaths from homicide. And if you had a time machine and could live in an historical era of your choice, then the homicide rate would also be the right statistic to look at, if you were concerned about violence.

|

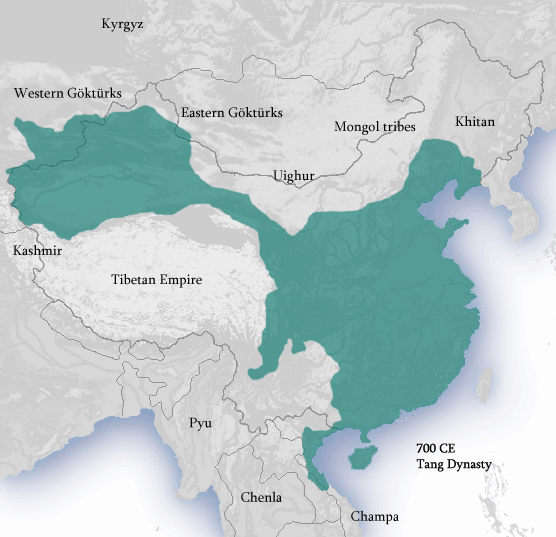

Map showing changes in borders of the Mongol Empire from founding by Genghis Khan in 1206, Genghis Khan’s death in 1227 to the rule of Kublai Khan (1260–1294). Image courtesy of Astrokey44 and Wikipedia.

Unfortunately, Pinker’s percentages don’t capture the idea of a homicide rate – a point also made by Elizabeth Kolbert in her critical review of Pinker’s book for The New Yorker. To see why, think of Genghis Khan and his Mongol armies. Genghis Khan was the founder of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), which controlled 16% of the world’s land area and held sway over 100 million people at its peak. According to Matthew White, Genghis Khan and his armies killed off about 11% of the entire human race (or about 40 million people) in the space of just 21 years (1206-1227). I should like to point out in passing that other authorities propose a much lower figure for deaths caused by Genghis Khan and his armies: Professor Rudolph Rummel only attributes 4 million deaths to Genghis Khan, but also estimates that “as many as 30 million people (about 13 percent of the world’s population)” were murdered by the Mongols during the 14th and 15th centuries. That’s a 200-year time period.

Numbers of victims aside, the question we really need to answer is: if you were living in Central Asia during the time of the Mongol Empire, what was the chance that you’d eventually be killed in some act of violence? Knowing the percentage of people that were killed in the worst massacre during that period is of little use unless you also know how long the massacre lasted, and whether there were any other major massacres during that century.

Pinker seems to have trouble grasping this mathematical point. “Imagine,” he writes in his response to Kolbert on his FAQ page, “that that slave trade was abolished after a year, or that Genghis Khan was defeated after a month, or that the Holocaust was called off after a week. Would we not judge those events as vastly less violent?” Yes, certainly we would. But we’re not judging events; we’re comparing the overall level of violence during various time periods. For instance, would a typical person living in the 8th century be at a higher or lower risk of being killed in wars and atrocities than an individual living in the 13th? To answer that question, you’d need to look at the annual death rate from wars and atrocities, per 1,000 people, and because the annual death rate might fluctuate markedly from year to year as atrocities come and go, you’d need to average the annual death rate out over the course of a century, in order to get a typical figure that represented your annual risk of dying as a result of an atrocity.

Let’s go back to the deaths caused by invading Mongol armies. The first flaw in Pinker’s argument is that it focuses on a single atrocity: for example, the killings committed by Genghis Khan and his armies. But if you were living in Central Asia during the time of the Mongol Empire, you’d obviously want to factor in later Mongol invasions as well, to get an overall picture of the annual risk of being killed as a result of an atrocity. The second flaw is that on Pinker’s logic, it wouldn’t matter whether the deaths caused by invading Mongol armies deaths took place quickly, over 20 years, or slowly, over 200 years, because the same number of people were still killed. But obviously, it does matter. People don’t live for 200 years, and in those days, even 50 years would have been quite a good innings. That’s why I would opt for the annual death rate from all atrocities occurring during a fixed time period (say, the 13th century) as the best measure of how violent that period was.

What percentage of people died from wars and atrocities in previous centuries?

The indefatigable Matthew White has attempted to calculate the percentage of all deaths occurring in the last few centuries that were due to wars and atrocities (massacres, slaughters and acts of oppression). Here are his figures:

20th century (see here:

White estimates that 5.5 billion people died during the 20th century, of whom 203 million died as a result of war, genocide, tyranny and man-made and/or intentional famine.

This means that 3.7% of all deaths in the 20th century were due to wars and acts of oppression, on Matthew White’s figures. Think about that. That’s an amazing 1 in 27 deaths, worldwide. I’d say that’s a pretty high figure.

19th century (see here and scroll to the bottom):

White estimates that about 4.3 billion people died during the 19th century, of whom 45 million died as a result of wars, oppressions and atrocities, and oppression. Matthew White comments:

Forty-five million unnatural deaths would be 1% of 4.3 billion deaths (or 1 out of every 96), considerably less than the percentage for the 20th Century.

White also mentions that a further 45 million people died in Third World famines in 1876 and 1896, which historian Mike Davis maintains were caused by the policies of European colonial powers. In his book, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World (2001) Davis argues that the business policies of the imperial European landlords, merchants and bureaucrats in the face of El Nino droughts intensified these famines and thereby caused millions of deaths. If we include these deaths, we get 2% of all deaths in the 19th century that were the result of acts of brutality.

18th century (see here and scroll to the bottom):

Matthew White estimates that there were 3,226 million (or approximately 3.2 billion) deaths worldwide during the 18th century. After tallying all the wars and atrocities he can locate in the historical records of that period, he writes: “Adding all the events listed here gives a very, very (very) tentative total of 18 Million unnatural deaths during the 18th Century.” White then calculates the percentage of deaths in the 18th century resulting from wars and atrocities: “Eighteen million unnatural deaths would be 0.6% of 3.2 billion deaths (or 1 out of every 179).”

White comments: “This is a lot lower than either the 19th or 20th Centuries death rates,” but then he adds a qualifying remark: “With a childhood mortality rate far higher than later eras, fewer people would live long enough to get caught up in wars and tyranny.” I have to say I don’t buy that. For most countries around the world outside Northern and Western Europe and the U.S.A., infant mortality rates in the 19th century would have roughly matched those of the 18th. And in any case, even back then, at least 40% of babies that were born made it to adulthood (see here). So even if we exclude people who died before reaching adulthood, it would still mean that only 1.5% (0.6% / 40%) of adult deaths in the 18th century resulted from wars and atrocities – and that’s assuming (very unrealistically) that no children were killed in wars and atrocities! That’s still well below that 20th century figure of 3.7% of all deaths that were due to wars and atrocities. So I am inclined to conclude that the 18th century was more peaceful than the 20th, after all.

What percentage of people died from wars and atrocities before the 18th century?

“What about earlier centuries?” I hear you ask. Following Matthew White, I’m going to use Carl Haub’s population table in his online article, How Many People Have Ever Lived On Earth?” (Carl Haub is a senior visiting scholar at the Population Reference Bureau.) Haub’s data for the period we are interested in is as follows:

1 A.D. Population 300,000,000 Birth rate: 80 per 1,000

1200 A.D. World Population: 450,000,000. Birth rate: 60 per 1,000.

1650 A.D. World Population: 500,000,000. Birth rate: 60 per 1,000.

I’m also going to assume, as a rough approximation, that the population growth in any given century prior to the 18th was practically zero, and that the death rate was therefore equal to the birth rate. From the above figures, we can therefore calculate the number of deaths in the first century A.D. as 2.4 billion (80 x 300,000), in the thirteenth century as 2.7 billion (60 x 450,000) and in the seventeenth century as 3 billion (60 x 500,000).

What these figures mean is that in order to get a figure of 1% of all deaths in any given century being due to wars and atrocities, you would need 24 million deaths from wars and atrocities in the first century, 27 million in the thirteenth century, and 30 million in the 17th century. To arrive at a figure of 3.7% of all deaths in any given century being due to wars and atrocities, which is White’s calculated percentage for the 20th century, you would need 88.8 million deaths from wars and atrocities in the first century, 99.9 million in the thirteenth century, and 111 million in the 17th century. But if we look at the actual death tolls from known wars and atrocities, which are conveniently summarized on the New York Times chart of atrocities based on Matthew White’s research, we find that there were about 20 million deaths from all recorded wars and atrocities in the first century, 45 million in the thirteenth century, and 52 million in the 17th century.

Now we can see why Professor Steve Pinker’s atrocity figures for times past are pretty small beer.

In the first century A.D., the Chinese Red Eyebrows revolt during the Xin dynasty (9-24 A.D.) killed 20 million people, or 5.9% of the human race living at that time, according to Matthew White. But that’s only 0.83% of the 2.4 billion people who died during the first century – far less than the 3.7% of people who died from wars and atrocities in the 20th century. What’s more, there are no records of any other comparable wars or atrocities from the first century, as anyone can easily verify from inspecting The New York Times chart of historical atrocities, based on research by the atrocitologist Matthew White, who is one of Pinker’s main sources for information relating to acts of violence in the past. As we can see, the Red Eyebrows revolt dwarfs all other atrocities occurring in the first century. The Roman-Jewish wars (66-135 A.D.) killed about 350,000 people, or about thirty times less.

During the third and fifth centuries, the Three Kingdoms Revolt in China and the fall of Rome killed off 4.1 million people and 7 million people respectively, according to Matthew White’s figures. Once again, there are no records of any other wars or atrocities of comparable magnitude from those centuries. 4.1 million people and 7 million people represent 0.17% and 0.3% respectively, or far less than 1%, of the approximately 2.4 billion deaths that took place in each century.

The next big event is the An Lushan Rebellion in China, in the eighth century. According to White, it killed 13 million people, or 5.9% of the world’s population. But once again, it’s a blip: there are no other wars or atrocities in that century of comparable magnitude. The 13 million deaths from that rebellion (on White’s figures) represent a mere 0.54% of all the deaths occurring in the eighth century.

“What about the 13th century?” I hear you ask. Now we’re talking big, if we place credence in the figures provided by Matthew White, who estimates that Genghis Khan’s armies killed off 40 million people. (Fellow atrocitologist and historian Professor Rudolph Rummel estimates the death toll at 4 million, but we’ll go with White’s figures for now.) In the same century, we have 0.8 million from Hulagu Khan’s Mongol invasion, 1 million from the Albigensian Crusade (a five-fold exaggeration, as I showed in my last post), 1.5 million (on a pro-rata basis) from the other Crusades (3 million deaths over two centuries – again a highly inflated figure), and about 1.5 million (on a pro-rata basis) from the Mid-East Arab slave trade (18.5 million deaths over 1200 years). On White’s figures, that comes to 44.8 million deaths, which is about 1.66% of the 2.7 billion deaths occurring in the 13th century.

In the fourteenth century, we have 17 million deaths caused by the conqueror Timur (Tamburlaine) from 1370 to 1405, plus 7.5 million deaths from the fall of the Yuan dynasty, 0.5 million deaths from the Bahmani-Vijayanagara war, 1.5 million deaths (on a pro-rata basis) from the Mid-East Arab slave trade and 1.9 million deaths (on a pro-rata basis) from the Hundred Years’ War (3.5 million x 64 years/117 years), giving a total of 20.9 million deaths, or about 0.77% of the roughly 2.7 billion deaths occurring in the 14th century.

The seventeenth century was a bloody one, they say. The Ming dynasty collapsed, killing 25 million people, the Thirty Years War an estimated 7.5 million, the Time of Troubles 5 million, and the Mughal ruler Aurangzeb (1681-1707) 4.6 million people, respectively. White estimates the death from institutional oppression associated with the Atlantic slave trade and the conquest of the Americas at 16 million spread over about 350 years and 15 million spread over about 400 years respectively, so we can calculate the deaths in the 17th century on a pro-rata basis at about 4.6. million and 3.75 million respectively. And let’s not forget the 1.5 million deaths (on a pro-rata basis) from the Mid-East Arab slave trade. That gives us 52 million deaths, or about 1.73% of the 3 billion deaths occurring in the 17th century – quite a high figure, but still well short of the 3.7% of deaths caused by wars and government atrocities in the 20th century.

The conclusion seems inescapable: if we look at known wars and atrocities occurring in the various states that have existed over the last 2,500 years, we find no support for the thesis that they claimed a higher percentage of lives in times past than in the 20th century. If anything, the reverse is the case.

Is this a fair comparison? Shouldn’t we just focus on adult deaths that were caused by violence?

Perhaps Professor Pinker will want to object that infant mortality was higher in those days, so we should look at the percentage of adults that were killed by violence, rather than the percentage of all people who died in that century. I have to say I don’t agree with this argument: babies and children can be victims of wars and government brutalities, too. But let’s go along with this proposal, and exclude people who died in infancy and childhood.

Assuming that about 40% of all babies that were born made it to adulthood, this would mean that if 1.5% (3.7% x 40%) of all deaths occurring in earlier centuries were caused by war and atrocities, then that would be an equivalent level of violence to the 3.7% of deaths that were caused by wars and government atrocities in the 20th century. (Readers will notice that I’m very generously assuming here that infant mortality was zero in the 20th century.)

What follows then? By Pinker’s own figures, only the 13th and the 17th centuries, with 1.66% and 1.73% (respectively) of deaths that were caused by wars and atrocities, come up to the 1.5% level needed to match the violence of the 20th century. All other centuries fall far short.

What about prehistoric violence, and violence among contemporary hunter-gatherers?

|

Neanderthal man is believed to have practiced cannibalism. Image courtesy of Neanderthal Museum, Stefan Scheer and Wikipedia.

Pinker makes a strong case when he claims that prehistoric and tribal societies were a lot more violent than our own society, even at its worst. As this slide from Pinker’s online talk, A History of Violence (27 September 2011) shows, the average percentage of deaths caused by violent acts in prehistoric societies seems to have been a little over 15%, judging from the 20 or so archaeological sites for which analyses have been performed. That’s several times higher than the percentage of deaths in the 20th century that were caused by wars, man-made famines and atrocities (which atrocitologist Matthew White estimates at 3.7%). The same picture emerges when we look at modern hunter-gatherer and tribal societies: the average rate of war deaths in the 27 societies shown on this slide is about 500 per 100,000 people per year, or 0.5%, which is about eight times higher than the comparative rate for the 20th century (60 per 100,000 people per year), even if we include all atrocities. (And if the higher death rate from all causes in these tribal societies were reduced to a level typical of developed countries, the percentage of all deaths which are caused by violent acts would be even higher than it is now.)

I should point out that Pinker’s claim that prehistoric societies were more violent than contemporary ones has been challenged by some reviewers. Thus Edward S. Herman and David Peterson, in a very hostile left-wing review of Steven Pinker’s data, titled, ‘Reality Denial: Steven Pinker’s Apologetics for Western-Imperial Violence’, write:

Also revealing is the cavalier attitude that he [Pinker] takes towards his data, and the huge fudge-factors he entertains. He offers a 0-to-60 percent range for the bodies recovered from one subset of 21 “nonstate” graves he labels “Prehistoric,” and claims that this series of estimates that are literally all over the map can be reduced to a meaningful final average of 15 percent. Similarly, he offers a 14 percent average for violent deaths among the 8 graves he designates as “Hunter-gatherers,” and a 24.5 percent average for the 10 “Hunter-horticulturalists” graves.

But were the bodies that Pinker alleges can be associated with violent deaths combat-related deaths, sacrifices, or accidents? Were the artifacts recovered with these bodies evidence of weapons or other kinds of tools? In cases when they are clearly weapons, were they also causes of death or the purely symbolic accoutrements of burial?

Indeed, in one careful assessment of “Pinker’s List” of the 21 “Prehistoric” graves, the anthropologist R. Brian Ferguson concludes that this list “consists of cherry-picked cases with high casualties,” and that in passing-off these “highly unusual cases” as representative of “prehistory,” Pinker distorts “war’s antiquity and lethality.”

|

Cannibal feast on the Island of Tanna, New Hebrides. Painting by Charles E. Gordon Frazer (1863-1899). Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Likewise, Pinker’s claims about contemporary hunter-gatherer brutality have been challenged by Steve Corry, director of Survival International, an advocacy movement for tribal peoples, who has recently written a blistering critique of Pinker’s book, titled, The case of the ‘Brutal Savage’: Poirot or Clouseau? Why Steven Pinker, like Jared Diamond, is wrong. The following is a brief excerpt from the section dealing with hunter-gatherers:

…[W]hat’s the ‘evidence’ concerning the violence of both our ancestors and tribal peoples today? Pinker lays this out in what I call his ‘sawtooth’ graph. It compares the percentage of ‘deaths in warfare’ in a miniscule selection of four human ‘categories’: ‘prehistoric archaeological sites’; ‘hunter-gatherers’; what he calls ‘hunter-horticulturalists & other tribal groups’; and, finally, ‘states’.

The ones with the highest deaths in each category are at the top, which produces the ‘sawtooth’ shape, a series of diminishing triangles one on top of the other…

Leaving aside (for reasons of space!) those he categorizes as ‘hunter-gathers’, the thousands of remaining tribal peoples in the world are represented by just ten; half of those are from New Guinea.[xx] There are about a thousand languages in New Guinea, so if we equate these roughly to ‘peoples’, then Pinker’s ‘sample’ amounts to just half of one percent of the ‘tribes’ on the island. These are not selected randomly, but are just those few societies where researchers have collected information on causes of death. (As I also point out elsewhere, few scholars looking for data on killing are likely to study peaceful societies, and almost none are cited.)[xxi]

One of the New Guinea tribes listed is the Dani of West Papua, an area invaded and brutally suppressed by Indonesia since the 1960s. As spokesman, Markus Haluk, retorted (over Jared Diamond’s book), ‘The total of Dani victims from the Indonesian atrocities… is far greater than those from tribal war.’[xxii] Why aren’t those deaths in Pinker’s graph?

It is simply not scientific to generalize about a thousand New Guinea tribes on information from just five. Let’s focus instead on who’s left.

As always nowadays, whenever the ‘Brutal Savage’ myth is invoked, Napoleon Chagnon’s ‘sweaty, hideous’[xxiii] Yanomami is guaranteed to career (I use the word advisedly) cinematically into sight, screaming blood-curdling growls and wails, and oozing green snot and red blood.[xxiv] Although familiar to American college students, virtually every other scholar who has lived with the tribe considers Chagnon’s characterization to be fictional.[xxv]

Four of the five cited non-New Guinea societies are from the Amazon, and two of those are, as always, Yanomami.[xxvi] Looked at another way, no less than twenty percent of the data Pinker uses to categorize the violence of the entire planet’s tribal peoples (excluding ‘hunter-gatherers’) is derived from a single anthropologist, Napoleon Chagnon – whose data has been severely criticized for decades.[xxvii] To put this yet another way, nearly half of all the thousands of the world’s tribal peoples outside New Guinea (again excluding those Pinker has decided are ‘hunter-gatherers’) are condemned as ‘Brutal Savages’ on the strength of one man’s account of one tribe. Chagnon’s so-called data, moreover, was not collected simply through dispassionate observation, but somehow involved upsetting more or less everyone he worked with, or even came across. [xxviii] He cheerfully admits to causing some Indians considerable distress, and has even decided that the Yanomami came close to killing him on several occasions.

It needs to be borne in mind that statements about prehistoric or non-literate societies must be hedged with qualifications, owing to the uncertainties involved. Nevertheless, in view of the fact that the percentage of deaths by violence in the graphs cited by Pinker – and so far, no-one has produced better ones – is so much higher at prehistoric burial sites than in the proportion of violent deaths occurring in modern society, I am (reluctantly) inclined to agree with Pinker’s general claim that the institution of the State has probably played a role in reducing individual vendettas, centralizing the use of force, and thereby reducing the percentage of deaths by violence. (I say “reluctantly,” because I am at heart an anarchist. But facts must be faced.)

Granting that the level of violence was higher in prehistoric and tribal societies, what follows from this? As Pinker himself puts it, what it shows is that “when it comes to life in a state of nature, Hobbes was right, Rousseau was wrong.” Government is better than anarchy: life in the state of nature really is nasty, brutish and short. This may be because intra-tribal fighting is more common in tribal societies, or it may be because inter-tribal warfare is more common, or both. But it does suggest that the existence of a State plays an important role in reducing violence. What it doesn’t prove, however, is the Utopian thesis that the world is getting less violent, over time. Nor does it tell us how much power the State should arrogate to itself, in order to curb acts of violence.

What about unrecorded acts of violence?

The atrocitologist Matthew White is fully cognizant of the fact that the level of violence from historically recorded wars and atrocities in previous centuries is well below that of the 20th centuries, but he cautions against inferring too much from this, on his Web page, Selected Death Tolls for Wars, Massacres and Atrocities Before the 20th Century:

There are undoubtedly many other events that were never recorded and have now faded into the oblivion of forgotten history. This makes it difficult to prove whether brutality is waxing or waning in the long term. Maybe the 20th Century really was more barbaric than previous centuries (as some people say), but you’ll need more complete statistics to prove it.

That’s a fair point. There’s a lot about the past that we don’t know. But the data we have contradicts Pinker’s progress thesis: the 20th century seems to have been more violent than its predecessors. As I’ll argue below, this perception is probably an accurate one.

Professor Pinker’s lame response to the fact that 20th century violence is awkwardly high is to appeal to unrecorded genocides in bygone eras. In his online talk, A History of Violence (27 September 2011), Pinker quotes historians Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn, who write in their book, The History and Sociology of Genocide, “Genocide has been practiced in all regions of the world and during all periods in history.” However, he says, no-one bothered recording the number of victims, as “their fate was simply too unimportant.” For instance, the Assyrians were legendary for their ruthlessness, and they are said to have engaged in genocide, but they didn’t bother recording numbers of victims.

|

Assyrian attack on a town with archers and a wheeled battering ram; Assyrian Relief, North-West Palace of Nimrud (room B, panel 18); 865–860 BC. Image courtesy of British Museum and Wikipedia.

However, scholars can estimate that the Assyrian wars of conquest killed about 100,000 people. Given a birth rate of 80 per 1,000 as per 1 A.D. (see Carl Haub’s online article, How Many People Have Ever Lived On Earth?”), and given a world population of 50,000,000 circa 1,000 B.C., and a death rate roughly equal to the birth rate, we can calculate that about 400 million people worldwide would have died in the century when the Assyrian armies were conquering the Middle East. To get a worldwide death rate of even 1% from acts of violence in that century, we’d need 4 million deaths. To get that from war, 40 armies worldwide would have to have killed on the same scale as the Assyrians, and in the same century. I have to say I find that highly implausible. Armies like that of the Assyrians weren’t exactly a dime a dozen. At their peak, the Assyrians were greatly feared, precisely because they were in a class of their own.

In his online talk, A History of Violence (27 September 2011), Pinker also mentions genocides committed by “the Athenians in Melos; by the Romans in Carthage; and during the Mongol invasions, the Crusades, the European wars of religion, and the colonization of the Americas, Africa and Australia.” Yes, but we’ve already calculated the statistics for most of these events, and with the exception of the 13th and 17th centuries, the percentage of deaths that were caused by acts of violence in previous centuries doesn’t even come close to the percentage killed from wars and atrocities in the 20th century.

Professor Rudolph Rummel has stated that he regards the 20th century as the most violent century on record. In his earlier writings, however, Rummel argued that unrecorded acts of violence may have taken place in the past on a horrific scale, making it impossible for us to judge which century was the bloodiest. I shall discuss Rummel’s arguments below; all I will say for now is that the numbers that Rummel is forced to postulate are simply historically incredible. (Perhaps that’s why Rummel subsequently revised his views.)

Shouldn’t we just be using raw homicide rates?

A final argument that Pinker could validly make is that instead of trying to ascertain the percentage of deaths that were due to acts of violence in a given era, we should be simply trying to measure the annual death rate from acts of violence in each era. That’s what you’d want to know, if you had a time machine and you were dropping in on that period. In that case, the relevant statistic would be the death rate from acts of violence per 100,000 people per year.

If we apply this logic to wars and atrocities in previous centuries, we obtain the following results.

1st century: 20 million deaths from wars and atrocities over 100 years. World population: 300 million. Death rate from wars and atrocities: 66.67 per 100,000 people per year.

13th century: 45 million deaths from wars and atrocities over 100 years. World population: 450 million. Death rate from wars and atrocities: 100 per 100,000 people per year.

17th century: 52 million deaths from wars and atrocities over 100 years. World population: 500 million. Death rate from wars and atrocities: 104 per 100,000 people per year.

20th century: 203 million deaths from wars and atrocities over 100 years. Mean world population: 3,150 million. Death rate from wars and atrocities: 64.44 per 100,000 people per year.

I should point out that Professor Rummel’s estimate for deaths due to wars and atrocities in the 20th century is considerably higher than White’s, at 297 million. Using that figure, the death rate from wars and atrocities in the 20th century was 94.29 per 100,000 people per year – about the same as for the 13th and 17th centuries.

To be completely fair, we should also add those deaths that were due to individuals murdering each other to those deaths that were caused by wars and atrocities, in order to calculate the total death rate from acts of violence. For the 13th and 17th centuries, I shall assume a worldwide death rate from homicide of 50 per 100,000 people per year – the same as the homicide rate in Europe for the year 1300. Back in those times, most of the world’s population would have been living in societies where the State was not very centralized, so the homicide rate would have been higher. This figure of 50 deaths per 100,000 people per year is likely to be somewhat high – it was probably much lower in China, for instance, and it is worth noting that even drug-torn Colombia currently has a homicide rate of “only” 38 per 100,000 people per year. In 2010, the worldwide homicide rate was 6.9 deaths per 100,000 people per year, according to the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime, and as I have no worldwide figures for the early decade of the twentieth century, I shall simply apply this figure to the 20th century as a whole.

So there we have it. Bending over backwards to be as fair as possible, we get a total death rate from all acts of violence of 116.67 (= 66.67 + 50) per 100,000 people per year in the first century A.D., 150 in the 13th century, 154 in the 17th century and 71.3 (or 101.2 on Rummel’s figures) for the 20th century.

Remember: the 13th and 17th were the bloodiest centuries in times past. Other centuries were much less violent. If Rummel’s figures for 20th century violence are correct – and I will argue they are – then our own 20th century was more violent than the first century A.D., but somewhat less violent than the 13th and 17th centuries.

So, why were the 13th and 17th centuries so bloody?

Some readers may be wondering why the 17th century was so bloody. The ever-helpful Matthew White provides a ready explanation in a footnote:

The primary cause of this was a quantum leap in military technology. The development of efficient muskets and artillery was allowing entire civilizations to be brought under the command of a single dynasty, creating so-called Gunpowder Empires. Although in later centuries, these new Empires would be a stabilizing influence, they began by destroying ancient power balances and unleashing chaos.

A similar theme emerges when we look at the 13th century: the Mongol armies had an immense military advantage over other world powers, according to the Wikipedia article, Mongol military tactics and organization:

The Mongol military tactics and organization helped the Mongol Empire to conquer nearly all of continental Asia, the Middle East and parts of eastern Europe. In many ways, it can be regarded as the first “modern” military system.

The original foundation of that system was an extension of the nomadic lifestyle of the Mongols. Other elements were invented by Genghis Khan, his generals, and his successors. Technologies useful to attack fortifications were adapted from other cultures, and foreign technical experts integrated into the command structures.

For the larger part of the 13th century, the Mongols lost only a few battles using that system, but always returned to turn the result around in their favor. In many cases, they won against significantly larger opponent armies. Their first real defeat came in the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, against the first army which had been specifically trained to use their own tactics against them. That battle ended the western expansion of the Mongol Empire, and within the next 20 years, the Mongols also suffered defeats in attempted invasions of Vietnam and Japan.

What does this imply for violence in the 20th century?

So, major improvements in military technology tend to cause an increase in acts of violence. What does that imply for the 20th century? Hmm. Let’s recall some of the military innovations we saw in that century. Airplanes, poison gas, tanks, bacteriological warfare, atomic bombs, ICBMs, killer satellites… Other things being equal, you would expect it to be a rather violent century, wouldn’t you? You certainly wouldn’t expect it to be a quiet one.

The 20th century was not merely distinguished by technical advances on the battlefield. There were also advances in techniques used for mass killing (think of the gas chambers) and torture (think of the nasty techniques developed by the Nazis and the Soviets). So it is not at all surprising that there was a sudden surge in violence used by governments against innocent civilians, in the 20th century. The Assyrians had no way to gas people they didn’t like; the Nazis did. Is it any wonder, then, that the 20th century was a particularly bloody one?

What I’m suggesting, then, is that given the exponential increase in scientific and technical knowledge in the 20th century, it would be a sociological miracle if this knowledge was not misused. And we can be sure that there will be further military advances in the 21st and 22nd centuries. Pace Pinker, the last thing we have any right to expect in the future is a long-term decrease in violence over time.

Professor Pinker’s very faulty statistics

Steven Pinker’s book, ‘The Better Angels of our Nature’ has attracted widespread attention in the media. However, few of the journalists commenting on White’s book appear to realize that the historical statistics cited by Pinker to support his claim that violence has been declining over the course of time are for the most part either bogus or highly questionable. In this section, I’d like to take a look at some examples of Pinker’s historical howlers. These examples have been skillfully dissected by Humphrey Clarke, an amateur historian who is one of three contributors to Quodlibeta, a blog primarily concerned with religion, science, history and their interface.

(a) Did the An Lushan revolt really kill 36 million people in the eighth century?

|

Tang Dynasty circa 700 AD. From Albert Herrmann (1935), History and Commercial Atlas of China, Harvard University Press. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Let’s begin with the atrocity which Pinker considers to have been the worst in history, in terms of the proportion of the world’s people that it killed: the An Lushan revolt, a rebellion against China’s Tang dynasty that was launched by a general named An Lushan in 755, sparking a civil war across northern China that lasted eight years and, according to Pinker, killed about 36,000,000 people before it was crushed. Amazingly, Wikipedia continues to credulously cite this figure in its List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll.

Thirty-six million people? That’s an extraordinarily high figure, and even Matthew White, one of the atrocitologists most frequently cited by Professor Pinker, doesn’t buy it. White, who is a very fair-minded individual, cites the following statement from an article by J. D. Durand, (“The population statistics of China, AD 2 – 1953,” Population Studies, 1960, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 209, 223):

Many historians have affirmed that 36 million lives were lost as a result of the violent event, but Fitzgerald and others have shown that this is incredible. Even if such a huge loss were conceivable, it would be naive to suppose that an accurate count could be carried out in the midst of the ensuing chaos.

White also quotes the following statement by Fitzgerald, in China: a Short Cultural History, 1973, pp. 312-315:

The real cause of the decline in the figures for the censuses after the rebellion was the dispersion of the officials who had been in charge of the revenue department.

Matthew White, the atrocitologist whom Pinker cites most frequently in his book, actually suggests a much lower figure of 13 million, for reasons which he discusses on his Website here. This was the figure which White used in his recent best-seller, The Great Big Book of Horrible Things, for which Pinker wrote a glowing Preface. Hmmm. It seems that Pinker and White got their communication lines crossed.

It turns out that the figure of 36 million is based on Chinese census records, which were extremely unreliable during those times when the government of China was not effectively centralized. The census taken in 753, at the peak of the Tang dynasty and on the eve of the An Lushan Rebellion, recorded a population of 52,880,488, while the census of 764 (just after the rebellion) recorded a population of only 16,900,000. However as Matthew White himself acknowledges on his Website, “most scholars believe the numbers to be wrong.”

White himself believes that about 13 million people perished as a result of the An Lushan Rebellion, on the grounds that census counts conducted after the Rebellion show a consistent drop in the number of households:

In the seven counts before An Lushan’s Revolt, the census repeatedly found between 8 and 9 million households, and then, in the seven counts following the rebellion, the census consistently found no more than 4 million. Even a century after the revolt, in 845, the Chinese civil service could find only 4,955,151 taxpaying households, a long drop from the 9,069,154 households recorded in 755. This indicates that the actual population collapse may have been closer to one-half, or 26 million. For the sake of ranking, however, I’m being conservative and cutting this in half, counting only 13 million dead in the An Lushan Rebellion.

White makes no claim to being an historian, and his methodology is certainly prudent. There are times, however, when an expert’s knowledge is called for. And according to leading authorities, the population seems to have risen, rather than fallen, during this period of China’s history.

The verdict of historians: why Pinker’s figure of 36 million deaths is utterly incredible

As amateur historian Humphrey Clarke points out in a highly skeptical review entitled, Steven Pinker and the An Lushan Revolt (Sunday, November 06, 2011), a figure of 36 million deaths that would mean that two-thirds of the entire population of Tang dynasty China was killed in the space of just eight years. Or putting it another way:

If you scale for the mid 20th century’s population you would end up with an equivalent toll of 429,000,000 people. That would indeed be an astonishing high death rate…

Alarmed by the fact that he could find no respected Sinologists endorsing this figure, Clarke decided to do some homework:

Accordingly I have worked through a number of works such as the ‘Cambridge History of China Vol. 3’, Mark Edward Lewis’s ‘The Chinese Cosmopolitan Empire – the Tang Dynasty’ and David Andrew Graff’s ‘Medieval Chinese Warfare’ to see if they can shed greater light on what is now claimed to be the greatest holocaust in human history.

So, what’s wrong with Pinker’s figure of 36 million? Several things.

As Clarke points out in his review, there are good reasons to be skeptical of the census figures following the An Lushan rebellion:

Firstly, up until the modern age, population counts were sporadic and incomplete… Only a few landmark censuses from the pre-Song era [i.e. prior to 960 A.D. – V.J.T.] are taken to be reasonably reliable and the taxation records are frequently disrupted by war and administrative chaos…

Secondly the census figures vary wildly depending on the contemporary level of government control. For example, in the reign of Taizong from 626 to 649, only 3,000,000 households were registered. Under the previous Sui dynasty (581-618) the figure had been 9,000,000 households. According to Richard Guisso in the Cambridge History of China this ‘”sensational decline was not the result of catastrophic loss of life during the civil warfare of late Sui and early T’ang, but of simple failure by the local authorities to register the population in full. Even in the first years of Kao-tsung’s reign only 3,800,000 households – certainly far less than half of the actual population – were registered. Considerably more than half of the population was thus unregistered and paying no taxes“‘ (p. 297, Cambridge History of China). This shows that in times of difficulty the highly centralised taxation system could break down – resulting in half the population or more being omitted from the census.

Wait a minute. Half the population of China was omitted from the census during times when centralized government wasn’t working? So, how effective was central administration after the An Lushan rebellion? Clarke has thoroughly researched this question. He tells us:

After the An Lushan revolt the situation reached crisis proportions and a new period of warlordism and regional autonomy emerged. The Tang had survived only by carrying out a general decentralisation of administrative power and dispersing power through a new tier of provincial governments. Despite the restoration of peace the empire remained in a state of chaos. China broke into many regions who collected their own taxes and remitted only a small portion to the central government. The Tang could no longer update its registers and chart landowning; local tax records were destroyed, scattered and rendered obsolete. As Graff writes:

After the An Lushan rebellion, the Tang court lost the ability to enroll, enumerate, and impose taxes directly upon the majority of China’s peasant households. This development is dramatically illustrated by the decline of the registered population from approximately nine million households in 755 to less than two million in 760. (p. 240 – Medieval Chinese Warfare)

So according to Graff, who is acknowledged expert on medieval Chinese warfare, the population decline recorded in the Chinese census of 764 doesn’t mean that a massacre of 36 million people occurred. Rather, what it indicates is that after the An Lushan rebellion, “the Tang court lost the ability to enroll, enumerate, and impose taxes directly upon the majority of China’s peasant households.” Clarke concludes:

The post rebellion census figures cannot then be relied upon when estimating the impact on the empire’s population in the 8th century and there are no signs of a catastrophic two thirds population loss…

Humphrey Clarke summarizes the evidence as follows:

The estimates given by the great Harvard sinologist John King Fairbank in ‘The New History of China’ (2006) are that ‘the empire’s population may have totalled 60 million in AD 80, 80 million in 875, 110 million in 1190’ (p 106). These are of course estimates but they show that the general impression from historians of the period is not one of catastrophic population decline followed by recovery – but of a slow and steady late medieval population boom coupled with a shift in population from north to south. Mark Edward Lewis remarks that:

Between 742 and 1080 (two years for which comprehensive census records have survived), the population in the north increased by only 26 percent, while that in the south increased by 328 percent.

C A Peterson in the Cambridge history of China notes that in the wake of the rebellion:

Large scale shifts of population took place. Many of the war affected areas in Ho-pei and Ho-nan were partially depopulated, and many people migrated to the Huai and Yangtze valleys and to the south (p. 496)

At the end of his review, Clarke concludes:

There are therefore plenty of reasons to be sceptical of Pinker’s claim that An Lushan’s revolt ranks as the most destructive war of all time. In fact he doesn’t appear to have done even the most basic research of research into the credibility of his figures; which is a shame because ‘The Better Angels of our Nature’ is a very good read and presents some interesting questions.

(b) How many people did the Mongols kill?

|

Persian painting of Hülegü’s army besieging a city. Note use of the siege engine. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In another post, provocatively titled, How bad were the Mongols? (December 13, 2011), amateur historian Humphrey Clarke takes a look at the violence wrought by the Mongols in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. He writes:

In ‘The Better Angels of our Nature’ Stephen Pinker (quoting White’s estimates again) claims that the hordes of Genghis Khan and his successors managed to wipe out 40,000,000 people. This puts them at second in the all-time ‘Possibly the worst things people have done to each other’ list with an adjusted death toll of 298,000,000 (mid-20th century equivalent)…

Nonetheless – while the Mongols themselves would have been absolutely delighted to have been credited with the annihilation of 40 million people in the 13th century (around 9% of the world’s population at the time) – the number seems pretty unlikely. It’s the same as the number of civilians killed in World War II with a vastly higher world population and more destructive forms of weaponry.

Chroniclers of the time spared no details in depicting the full horror of Genghis Khan’s military campaigns. For instance, the Mongol leader Hulagu claimed in a letter to Louis IX of France that he had killed two million people during the sack of Baghdad. However, as Clarke points out, there are excellent reasons for doubting this claim:

This would mean the Mongols were pulling off operations on the scale of the siege of Leningrad and the battle of Stalingrad regularly over the course of their conquests. According to Jack Weatherford in ‘Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World’ these figures are ‘preposterous’. David Morgan in ‘The Mongols’ is as sceptical, but less emphatic, regarding these estimates as not statistical information but instead ‘evidence of the state of mind created by the character of the Mongol invasion’.

Weatherford states that ‘conservative scholars place the number of dead from Genghis Khan’s invasion of central Asia at 15 million within five years’, however ‘even this more modest total…would require that each Mongol kill more than a hundred people’. If we took the chroniclers’ estimates, according to Weatherford this would mean ‘a slaughter of 350 people by every Mongol soldier’ (this would trump even the 87 people killed by Arnold Schwarzenegger during the course of the movie Commando).

Is there any other evidence, then, for the claim that Genghis Khan and his armies killed 40 million people? Clarke discusses the Chinese census figures:

The only way in which the 40 million figure given in ‘Better Angels of our Nature could be rendered plausible is if the statistics given for China from Sung and Chin times to after the expulsion of the Mongols in 1382 are accurate. These show a drop in population from 100 million to 70 million in 1290s [6] and 60 million in 1393 – a drop of 40 million. How responsible are the Mongols for this apparent holocaust?

We have already seen the problems with attempting to rely on the Chinese censuses which all too often appear to reflect the effectiveness of the central administration rather than the actual population. According to Timothy Brook in ‘The Troubled Empire’ many Chinese in Mongol areas were simply not reported, having been en-serfed and thus disappeared from the records altogether. Additionally the 14th century in China saw extensive flooding of the Yellow river and the subsequent famine, outbreaks of disease in the 1330s and a major outbreak of what is thought to have been the Black Death from 1353-4.

After soberly reviewing the evidence, Clarke formulates his own estimate of 11-15 million victims:

Any estimate has to be taken with a considerable pinch of salt. John Man estimates that the Khwarezmian massacres claimed 1.2 million lives – 25-30% of 5 million. Hulagu’s conquests may have claimed roughly the same number and a slightly lower total can be assumed for the incursions into Eastern Europe and Rus. Clearly the Chinese census cannot be taken at face value in estimating population lost & most of the total must be due to plague. Assuming the real decline was 30 million (allowing for a significant undercount in the censue) and Mongol actions accounted for 25% of deaths gives 7.5 million. This would give a grand total of 11.5 million over the course of around a century.

…11-15 million doesn’t seem outside the realms of possibility – a staggering total but still some way short of the inflated total given by Pinker [8]. If that figure is correct then the Mongol Conquests killed 2.5% of the world’s population (450 million) in over a hundred years – from the 1230s to the late 14th century. By contrast World War II managed to wipe out between 1.5 and 2% of the World’s population in only six years.

Pinker’s last hurrah: What about the Long Peace of 1945-1988?

But Professor Pinker isn’t finished yet. On his FAQ page, he readily concedes that “[t]echnology, ideology, and social and cultural changes periodically throw out new forms of violence for humanity to contend with,” but goes on to argue that “in each case humanity has succeeded in reducing them,” citing “statistical evidence for this cycle of unpleasant shocks followed by concerted recoveries.” He goes on to argue:

[A] century comprises a hundred years, not just fifty, and the second half of the 20th century was host to a Long Peace (chapter 5) and a New Peace (chapter 6) with unusually low rates of death in warfare.

Note those last two words: “in warfare.” The percentage of people killed in wars since 1945 has fallen dramatically. But 65 years is an historical eyeblink. And more importantly, most violent deaths worldwide aren’t war deaths, but democides. War deaths dropped after 1945; democides did not.

What’s a democide?

“What’s a democide?” I hear you ask. In his Chapter 2 of his book, Death By Government, the atrocitologist Rudolph Rummel defines democide as any act of murder committed by a government:

Democide: The murder of any person or people by a government, including genocide, politicide, and mass murder.

Genocide is defined as “the killing of people by a government because of their indelible group membership (race, ethnicity, religion, language).” Politicide is “the murder of any person or people by a government because of their politics or for political purposes,” while mass murder is “the indiscriminate killing of any person or people by a government.” These are all forms of democide. But they are not the only forms: the murder of even a single individual by the government would count as democide, too.

“But how do you define murder? And what counts an act of the government?” I hear many of you respond. Rummel addresses these questions in his Democratic Peace Q & A Web page:

[F]or deaths to be democide requires:

(1) that the death be intended, or the result of a wanton disregard of a high risk of death (as murder is defined in civil law), as in incarcerating people in a prison environment in which life expectancy is three to six months due to disease, malnutrition, exposure, and overwork; and

(2) that this be done by an agent of the government according to its policy, rules, high level orders, or high level acceptance (as in turning the other cheek). Silence, lack of punishment, or apparent lack of concern over such murdered is evidence of high government involvement and thus democide. Executions after a fair and open trial for crimes internationally considered the subject of severe punishment, as for murder, treason, brutal rape, etc., are excluded.

On Rummel’s definition, deaths in battle cannot count as democide: the cause of a soldier’s death is not his government, but an opposing army. Rummel argues strenuously that there is a significant moral difference between “those killed in combat and its crossfire, and those murdered by governments during the war (democide).” The latter includes not only the indiscriminate bombing of innocent civilians, but any government-sponsored killing of civilians or POWs. Thus most of Genghis Khan’s victims, on Rummel’s definition, were victims of democide rather than warfare as such: they were massacred as Genghis Khan’s armies swept through cities in Central Asia, slaughtering every man, woman, child and animal they could find, as they were officially ordered to do. Likewise, according to Rummel, most of the 65,000,000 people who died in World War II were innocent civilians who were murdered by some government; only 15,000,000 or so were killed in battle and military action.

Rummel concludes that in every century, battle deaths pale in comparison to deaths from democide, such as massacres, executions, genocides, sacrifices, burnings, the slaughter of infants at the behest of the government, and deaths caused by mistreatment (e.g. not feeding prisoners of war).

108 million people were killed by governments during Professor Pinker’s Long Peace

|

Mao Zedong with his fourth wife, Jiang Qing, 1946. According to Professor Rudolph Rummel, Mao Zedong was responsible for the deaths of 77 million people. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Professor Pinker defines two periods of peace subsequent to World War II: the Long Peace (1945-1988), and the New Peace (1989-2005). The important point that emerges from Rummel’s research is that contrary to Pinker’s thesis that “the second half of the 20th century was host to a Long Peace”, it was actually a time of unparalleled democide. One dictator alone – Mao Zedong – killed about 77 million of his own people, according to Rummel’s calculations. (Rummel at one time estimated Mao’s victims at 38,702,000, but later increased his original estimate by 38,000,000 to 76,702,000, after reading convincing evidence that Mao had full knowledge from the very beginning of the tens of millions of deaths resulting from his disastrous Great Leap Forward of 1958-1962, but deliberately chose to do nothing about these deaths.) In addition, Rummel’s research shows that 22,485,000 people (15,613,000 plus 6,872,000) died from democide in the Soviet Union after the end of World War II, as well as 2,035,000 in Cambodia from 1975-1979, 1,670,000 in Vietnam from 1945-1987; 1,585,000 in Poland from 1945-1948; 1,503,000 in Pakistan from 1958-1987; 1,072,000 from 1944-1987; 1,663,000 in North Korea from 1948-1987; and 729,000 in Indonesia from 1965-1987 (see here). Altogether, that makes a total of 107,859,000 people murdered by governments around the world, from 1945 to 1987. Is this what Professor Pinker calls a Long Peace?

To quote the words of Professor Rudolph Rummel:

With the conclusion of that war and the discovery of the breadth and depth of the Holocaust, many demanded “Never Again.” But our history since has rather been: “Again, again, again, and again.”

Was the 20th century the bloodiest in history, in percentage terms?

Professor Rummel himself evidently regards the 20th century as a uniquely violent one. Here is his considered verdict on 20th century atrocities, according to his Democratic Peace Q & A Web page (February 20, 2005):

In short, the 20th C[entury] was by far the bloodiest in history both in total murdered and as a proportion of the world’s population.

Rummel originally estimated the total number of people killed by government brutalities in the 20th century at 174 million. He has recently revised this estimate to 262 million, after coming across damning evidence showing that Mao Zedong actually knew about the 38 million deaths caused by his Great Leap Forward 1958-1962 from the very beginning but didn’t care, and even more shocking evidence that European colonial powers (especially Belgium and France) knowingly caused the deaths of as many as 50 million people in Africa and Asia in the first half of the twentieth century, but took great pains to hide this information from the outside world. Rummel writes: “I’m willing to estimate that over all of colonized Africa and Asia [from] 1900 to independence, the democide was something like 50 million… These colonizers turned Africa into one giant gulag.”

Rummel also estimates the total number of war deaths (i.e. deaths in combat, according to his definition) during the 20th century at 35,000,000. That gives us a grand total of 297,000,000 people killed as a result of war and government-sponsored brutalities, during the 20th century.

Let’s think about what that means. The number of people who died during the 20th century was about 5,500,000,000, or 5.5 billion, according to Matthew White (see here). If Rummel’s figure of 297 million people killed by war or government-sponsored acts of murder is correct, this means that about 5.4% of the people who died in the 20th century were killed by war or atrocities. (As we saw above, Matthew White’s estimate was somewhat lower: 203 million, or about 3.7% of all 20th century deaths.) 5.4% of all deaths is a staggering number. It’s more than 1 out of every 19 deaths.

Rummel on unrecorded acts of violence

I should point out that in his earlier writings, Professor Rudolph Rummel avoids making the claim that the 20th century was the bloodiest in history. Indeed, in chapter 2 of his book, Statistics of Democide (Transaction Publishers, Rutgers University, 1997), he acknowledges that the list which he has compiled (see here and here) of atrocities occurring prior to the 20th century is “not a comprehensive or exhaustive collection“ and that consequently his estimates of deaths from atrocities prior to the 20th century are only “a small part of the real total.” Additionally, Rummel points out that his estimates overlook unrecorded everyday killings – for example, “a human sacrifice every Friday, commoners killed at the desire of nobles or Kings, an unwanted infant legally strangled, the assassination of a royal opponent, or the death of slaves or prisoners from mistreatment or overwork.” Similarly, in chapter 3 of his book Death by Government (Transaction Publishers, 1994), a stomach-churning chronicle of atrocities committed in times past, Rummel writes that his mid-range estimate of 133,147,000 people killed in all democides prior to the 20th century “probably reflects only a small fraction of those so wiped out during the thousands of years of written history”.

The foregoing points which Rummel raises are all valid ones. Even so, the notion that governments in ancient times were responsible for 1 in every 19 deaths – the proportion of people that were killed in government-sponsored acts of violence and wars in the 20th century – simply beggars belief.

|

A retiarius gladiator stabs at his secutor opponent with his trident. Mosaic from the villa at Nennig. Image courtesy of www.collector-antiquities.com and Wikipedia.

Consider the Roman Empire. I calculated above that during the first century A.D. when the world’s population was 300,000,000 and the annual death rate was about 80 per 1,000 people, a total of 2.4 billion people died worldwide. At that time, about 60,000,000 people, or one-fifth of the world’s population, lived within the Roman Empire. On a pro-rata basis, that would mean that about 480 million people died in the Roman Empire during the first century A.D. If 1 out of every 19 of these deaths was due to war or democide, that would make about 25 million deaths in the first century alone, or 250,000 deaths per year that were caused by war or democide. This is an absurdly high figure: Matthew White estimates the body count of the Roman Empire during its entire thousand-year history at 13 million, and his figures show that less than one million of these deaths occurred in the first century A.D. White’s figure includes not only wars but also executions, slave rebellions and the 1 million or so gladiators who died during the long history of the Roman Empire, as well as 7 million people who died in the 5th century A.D., in the wake of the fall of Rome. And forget about public executions: White estimates that no Roman Emperor in the first century was responsible for more than 10,000 executions. That’s a puny total alongside Stalin’s tens of millions of victims.

On the basis of these statistics, it is reasonable to conclude that no empire in times past could have been responsible for 1 out of every 19 deaths of its citizens on an ongoing basis, which is the proportion of the population killed in acts of violence in the 20th century – or even 1 out of every 27 deaths, if we adopt White’s estimate of 20th century violence.

Conclusion

We are forced, then, to the conclusion that the 20th century was a uniquely violent era in history. The history of the 20th century completely explodes Pinker’s thesis that violence is becoming less common over the course of time. The only thing to be said in favor of the 20th century’s level of violence is that bad as it was, the Stone Age was even worse, without 15% of all deaths being due to violence.

There is, however, one routine form of violence which Pinker should have spent a lot more time discussing in his book: infanticide. It is the Abrahamic religions which deserve the credit for ridding most of the world of this scourge. In doing so, they saved the lives of literally billions of people. Secular humanism had nothing to do with it. I’ll have more to say about this in my next post.