|

|

In a previous post two years ago, entitled, H. L. Mencken: Is this your hero, New Atheists?, I accused H. L. Mencken (pictured left) of lying and character assassination, in his reporting on the 1925 Scopes trial. Specifically, I charged that Mencken knowingly and deliberately made false statements about William Jennings Bryan (pictured right), a three-time Democratic Presidential candidate and eloquent orator, whose passionate opposition to Darwinism led him to volunteer his services an assistant prosecutor during the Scopes trial. To accuse a highly respected author such as Mencken of slander is a very serious matter, and in today’s post and an upcoming post, I’m going to substantiate this charge. Mencken not only slandered Bryan; he also slandered the people of Dayton, Tennessee.

What motivated me to write this article was my discovery that a statement attributed to William Jennings Bryan by H. L. Mencken in The Baltimore Evening Sun (July 17, 1925) that man is not a mammal, was a complete fake. An examination of the trial records reveals that Bryan never said any such thing. I can only conclude that Mencken lied – or that he had severe hearing problems! Unfortunately for Bryan, Mencken’s lie was widely repeated: it can be found in George Seldes’ book, The Great Thoughts (Ballantine Books, Random House, New York, 1985, revised and updated, 1996), in Vincent Fitzgerald’s biography, H. L. Mencken (Continuum Publishing Company, 1989; Mercer University Press, 2004), and at Positive Atheism’s Big List of Scary Quotations, as well as about 50 other online Web sites. That discovery made me wonder what else in Mencken’s reports was a lie. The short answer is: quite a lot. Mencken’s mis-representations fall under nine main headings:

(i) lying about the key point at issue in the Scopes Trial (which was not the theory of evolution, but the teaching of human evolution in Tennessee’s public high schools);

(ii) lying by omission about the biology textbook that was used in Tennessee’s high schools at that time, Hunter’s Civic Biology, (which didn’t just present the factual evidence for evolution, but also advocated obnoxious ideas, including racism and eugenics);

(iii) lying about William Jennings Bryan’s religious views (by presenting him as a Biblical literalist, when in fact he believed in an old Earth, was at least open to the possibility that animals had evolved, and only ruled out human evolution);

(iv) lying about what Bryan said at the Scopes trial (by falsely claiming that Bryan declared that “Man is not a mammal”, when what he actually held was that man was an exceptional mammal);

(v) lying about Bryan’s character (by unkindly depicting him as a petty, hate-filled character, when others who were present at the trial, including John Scopes himself, testified to his magnanimity, affability and pleasant personality);

(vi) lying about the extent of Bryan’s learning (by maliciously portraying Bryan as a man who hated learning, despite the fact that he had obtained three university degrees – a B.A., an M.A., an LL.B. – and been awarded at least seven honorary doctorates, and had actually read Darwin’s Origin of Species and Descent of Man);

(vii) lying about Bryan’s political views (by describing Bryan as a pathetic old man looking back to the good old days, when in fact, Bryan was a progressive who espoused women’s suffrage, as well as supporting the direct election of senators and a progressive income tax);

(viii) lying about the outcome of the Scopes trial (by portraying it as a crushing defeat for Bryan, when the trial transcript and other published accounts show that it was nothing of the sort); and

(ix) lying about the religious views of the people of Dayton, Tennessee (whom Mencken depicted as a bunch of yokels, flat-earthers and Biblical literalists, when in reality, a significant number of the townsfolk were Masons and Methodists, who did not espouse Biblical literalism).

I also unearthed several “bombshells” which severely undermined the credibility of H. L. Mencken’s coverage of the Scopes trial.

First, I discovered that as a reporter, Mencken had previously fabricated whole articles out of thin air. – a fact acknowledged by Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, in her biography, Mencken: The American Iconoclast (Oxford University Press, 2005). According to Rodgers, Mencken made up stories as a young cub reporter, and later on, in 1905, as the managing editor of the ailing Baltimore Herald. Given Mencken’s prior track record of making up stories, I began to suspect that his reporting of the Scopes Trial contained a very large dollop of fiction. My suspicion was reinforced when I re-read Mencken’s reports on the trial, and noticed that they said almost nothing about what actually happened in the trial courtroom, and were largely made up of amusing anecdotes about the town of Dayton, Tennessee, and the alleged antics of its inhabitants. Not once did Mencken quote the testimony of witnesses for either the prosecution or the defense, and not once did he quote the lawyers who interrogated these witnesses. I began to wonder why.

To make matters worse, I discovered that Mencken had actually perpetrated a hoax while he was in Dayton, reporting on the Scopes trial:

Aided by his friend, Edgar Lee Masters, Mencken attempted to perpetuate a hoax, distributing flyers for the Rev. Elmer Chubb. But the claim that Chubb would drink poison and speak in lost languages were ignored as commonplace by the people of Dayton, and only the Commonweal bit. (“Two Stories of the Scopes Trial: Legal and Journalistic Articulations of the Legitimacy of Science and Religion” by Lawrance M. Bernabo and Celeste Michelle Condit, in Popular Trials: Rhetoric, Mass Media, and the Law, edited by Robert Hariman, University of Alabama Press, 1990, pp. 76-77.)

Second, I found out that Mencken had a long-standing animosity towards William Jennings Bryan: in his own words, “I was against Bryan the moment I heard of him.” Mencken despised Bryan as a demagogue, and his reporting on Bryan’s career displayed a consistent bias, dating from as far back as 1904, some twenty-one years before the Scopes trial. For Mencken, everything that Bryan did was self-serving, including even his principled decision to resign on June 9, 1915 from his post as Secretary of State in Woodrow Wilson’s administration, in protest at what he saw as the Administration’s steady move towards war with Germany. After Bryan’s death, Mencken penned one of the most vituperative obituaries ever written, titled To Expose A Fool (The American Mercury, October 1925, pp. 158-160), in which he denounced Bryan as “a charlatan, a mountebank, a zany without any shame or dignity,” whose every political act was motivated by “ambition – the ambition of a common man to get his hand upon the collar of his superiors, or, failing that, to get his thumb into their eyes.” Common sense would tell us to be wary of accepting statements from such a biased source, regarding a man whom he viewed as a personal enemy.

Third, I discovered that Mencken’s own views on how evolution should be taught in schools were virtually the same as those of the modern-day Intelligent Design movement: he believed that the arguments in its favor should be presented to high-school students, along with the scientific objections to the theory. He believed that evolution should be taught not as a fact, but as a hypothesis accepted by most scientists. (Unlike Intelligent Design proponents, Mencken was so firmly convinced of the truth of Darwin’s theory of evolution, that he believed intelligent students would readily recognize its truth, upon seeing the evidence presented before them.) But the views of the creationist William Jennings Bryan on the teaching of evolution were not so very different to Mencken’s: he believed that the doctrine of the separation of Church and State precluded the teaching of the Genesis account, and he was also quite happy for the theory of evolution to be taught as a hypothesis in public schools. “Please note,” he explained, “that the objection is not to teaching the evolutionary hypothesis as a hypothesis, but to the teaching of it as true or as a proven fact” (quoted in Edward Larson’s Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate over Science and Religion, Basic Books, New York, 1997, 2006, p. 47). This is hardly the kind of statement we would expect to hear from a narrow-minded or bigoted man – and yet Mencken, in his coverage of the Scopes trial, consistently depicted Bryan in this manner, belittling him as a “fundamentalist pope” (Mencken Declares Strictly Fair Trial Is Beyond Ken of Tennessee Fundamentalists, July 16, 1925), whose followers “believe, on the authority of Genesis, that the earth is flat and that witches still infest it” (Tennessee in the Frying Pan, July 20, 1925).

Fourth, I was surprised to find out that although Mencken assisted the defense case in its attempt to have the Butler Act (which prohibited the teaching of human evolution in Tennessee’s public schools) overturned as unconstitutional, Mencken actually agreed with Bryan that the people of Tennessee had the right to set the science curriculum for government-funded schools, and that teachers should follow it. Thus in his column for The Nation (July 1, 1925), shortly before the Scopes trial started, he scoffed at the notion that “the conviction of Professor Scopes will strike a deadly blow at enlightenment and bring down freedom to sorrow and shame,” and argued that teachers in public high schools were merely pedagogues, who were paid to teach what the State tells them to. Mencken concluded that “no principle is at stake at Dayton save the principle that school teachers, like plumbers, should stick to the job that is set before them.” Bryan himself could not have said it better. In his reporting for the Baltimore Evening Sun, however, Mencken refrained from expressing these views, casting himself instead as a defender of Enlightenment values and portraying Bryan as a spokesman for the ignorant masses.

Fifth, I learned that there really was a conspiracy by Mencken and other journalists to “get Bryan.” I found that in the Scopes Trial, it was Mencken who had persuaded the defense lawyers that they should go after Bryan, with the aim of making him look ridiculous, instead of trying to defend Scopes.

The article on H. L. Mencken (1880-1956), written for the PBS “Monkey Trial” series, makes the following observations:

H. L. Mencken was responsible for suggesting to Clarence Darrow that he volunteer his services in the defense of John Scopes. Mencken hoped to witness a showdown between Darrow and prosecutor William Jennings Bryan. He wanted a front-row seat at an epic battle over science and religion. According to historian Kevin Tierney, “Mencken and Darrow really wanted in some sense to re-fight the Civil War. They were Northerners come down to tell the Southern yokels just how stupid they were.”…

He was a coiner of terms. It was Mencken who first used the phrase “Bible Belt” and Mencken who dubbed the Scopes trial the “monkey trial.”…

According to historian Paul Boyer, “Beneath Mencken’s ridicule of the ignorant hayseeds of America was a very profound suspicion of Democracy itself. Mencken really believed that there was a small elite of educated and cultivated and intelligent human beings, and then there were the masses who were really ignorant and capable of nothing but being led and bamboozled.”…

As the temperature inside and outside the courtroom soared, Mencken found an escape. He bragged to another reporter that he spent his evenings in an airy suite on Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga with bootleg liquor and a fan blowing a cool breeze over a bathtub of ice.

In the third week of the trial, after Darrow lost his temper and insulted the judge, it appeared the show would soon be over. Reporters packed away their notepads and typewriters. Even H. L. Mencken left town. He would miss the most dramatic moment of the trial, when Clarence Darrow interrogated William Jennings Bryan before thousands of people on the courthouse lawn.

The article on William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925), written for the PBS “Monkey Trial” series, adds:

Reporter H. L. Mencken came to Dayton expressly to “get Bryan.” In daily reports to The Baltimore Sun Mencken mocked Bryan as an “old buzzard” and a “tinpot pope.” “It is a tragedy indeed,” he wrote, “to begin life as a hero and to end it as a buffoon.”

I also discovered that most of the trial reporters displayed a consistent bias against Bryan and fundamentalism, in their stories. The reason for this bias, as I will show below, was an unquestioned belief on the part of the press in the in the ever-onward march of science and in the unstoppable tide of “intellectual progress” Any individual or communmity that attempted to halt this tide was consequently ridiculed as backward and ignorant: it was on the wrong side of history.

Sixth, I discovered an outrageous double standard in Mencken’s treatment of different Christian denominations in his reporting on the Scopes trial: he selectively targeted Christian fundamentalists – especially their most articulate spokesman, Bryan – but refrained from criticizing the Catholic Church, America’s largest Christian denomination (numbering about 17% of the population at that time), despite the fact that the Catholic Church’s position on evolution and the miracles recorded in Genesis and the rest of the Bible was virtually the same as Bryan’s. In a report for the Baltimore Evening Sun (June 15, 1925), Mencken had praised the “intelligent attitude” of the Catholic Church towards evolution, along with “[t]he Anglican, Orthodox, Greek and various other churches, including the Presbyterian,” while at the same time heaping scorn on “evangelicals” as “Ku Klux Protestants,” for their Biblical literalism. In his subsequent reporting on the Scopes trial, Mencken again and again referred to the people of Dayton, Tennessee as “fundamentalists,” whose closed minds were “unable to comprehend dissent from its basic superstitions, or to grant any common honesty, or even any decency, to those who reject them.” Mencken mocked the “fundamentalist rubbish” spouted by the prosecution in the Scopes trial, but reserved his most savage criticism for William Jennings Bryan, whom he mercilessly derided as a “fundamentalist pope” who “hates and fears” science, in his report of July 16, 1925. However, the evidence clearly shows that Bryan’s position on evolution and on Biblical miracles (which Mencken deemed incompatible with modern science) was strikingly similar to that of the Catholic Church.

Six Bombshells Relating to H. L. Mencken’s coverage of the Scopes trial

Here are six little-known but surprising facts I discovered about H. L. Mencken and the Scopes trial.

Bombshell Number One: As a journalist, Mencken fabricated stories several times

|

H. L. Mencken completely fabricated a newspaper story about the Battle of Tsushima, which sealed Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War. This picture shows Admiral Tōgō on the bridge of Mikasa, at the beginning of the Battle of Tsushima in 1905. The signal flag being hoisted is the letter Z, which was a special instruction to the Fleet. Image courtesy of P. D. Ottoman and Wikipedia.

Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, in her magisterial biography, Mencken: The American Iconoclast (Oxford University Press, 2005), relates that Mencken made up stories as a young cub reporter, and later on, in 1905, as the managing editor of the ailing Baltimore Herald. On May 28, 1905, Mencken decided to revive the circulation of his newspaper by concocting a front page story about the great battle which sealed Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese war, despite the fact that he, like most other American journalists, had absolutely no information about what had transpired during the battle: that would not be available for another two days. Mencken’s journalistic “scoop” was successful: his newspaper sold lots of extra copies with its sensationalistic front page story, and Mencken never got exposed for his deceit. (Only many years later, when he wrote his memoirs, did Mencken acknowledge what he had done.)

Despite the Herald‘s strict codes of accuracy and truthfulness (“No decent newspaper,” Mencken had declared, “runs falsehoods willingly and knowingly”), on May 28, 1905, during the Russo-Japanese War, Mencken abandoned his own principles.

The war had posed new challenges for all the major papers. Japanese censorship was tight. Wireless telegraphy and ocean cables were undependable. Most of the American dailies relied on the Associated Press or another major paper for war news, and few of the top papers … – let alone the Baltimore Herald – had correspondents or freelance writers in the field… (p. 96)

On May 28, the Tokyo Associated Press gave its first clue that a major battle had occurred. The morning newspapers, including the New York Times, reported that details of the day’s historic events were being withheld by the Japanese authorities…

“Like every managing editor of normal appetites I was thrown into a sweat by this uncertainty,” Mencken later recalled. He and his news editor stayed late at their posts, “hoping against hope that the story would begin to flow in at any minute, and give us a chance to bring out a hot extra.” The hours ticked by, but nothing came in.

Returning to his tiny office, Mencken sat down and typed in a plausible location: “Shanghai, China” for his dateline. His typewriter keys poised over the sheet of paper. “After that, I laid it on … with a shovel.”… Pring over maps, he and the news editor examined lists of commanders, names of ships, and photographs, embellishing what they thought would be a Japanese newspaper story of a Japanese victory to appear under the banner: “FLYING SHELLS STRIKE ROJESTEVENSKY; FIVE OF THE FUGITIVES ELUDE TOGO; SATURDAY’S BIG BATTLE DESCRIBED.”

Indeed, the battle was laid out in all its imagined detail. It began: “from Chinese boatmen landing upon the Korean coast comes the first connected story of the great naval battle in the straits of Korea.” It had been “a spectacle of extraordinary magnificence.” The day, Mencken typed, had been clear; the Russian ships grimy and unkempt; the roar of guns could be heard fifty miles from the scene of battle as the big battleship Borodino went down at the hour of noon. Here Mencken paused, adding, “or thereabout.” (p. 97)

Mencken never gave any indication as to how outrageous his exercise in manufactured news had been. Instead, all of this made for good material in his memoirs – which, he warned readers, was full of “stretchers.” But contrary to Mencken’s claim, not every detail of the battle had been correct, as alert Herald readers soon learned. It had been a misty day, not a clear one; the battle did not begin at noon but during the evening; Borodino did not fit the description of being unkempt, having recently been repaired…

Mencken had been criticized before for making up stories as a cub reporter. Even then, the paper’s youngest star had been given the benefit of the doubt, though it should be noted that by 1905-06 the practice was being condemned with far more vehemence than in 1899. As an editor, Mencken had shown no reluctance to confront such renegade behavior on the part of his staff. But when it came to his own story, and trying to revive the circulation of the ailing Herald, Mencken avoided any questions about his actions. (p. 98)

Bombshell Number Two: Mencken had a long-standing grudge against Bryan

|

Mencken wrote in his obituary of Bryan, “If the fellow was sincere, then so was P.T. Barnum.” The caption in the poster above reads: “The Barnum & Bailey greatest show on earth Wonderful performing geese, roosters and musical donkey”. Chromolithograph. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, the Strobridge Lithography Company, and Wikipedia.

I also discovered that by his own admission, Mencken had a long-standing dislike of Bryan. As he writes in his book, My Life as author and editor (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1992), “I was against Bryan the moment I heard of him.” Writing for the Herald in 1904, Mencken likened Bryan’s political farewell to a tragic play – a metaphor he would use again 21 years later, when reporting on the Scopes trial. According to Fred Hobson’s Mencken: A Life, it was Mencken who persuaded Clarence Darrow to undertake Scopes’ defense on the Scopes trial, and it was also Mencken who suggested to Darrow the idea of putting him on the stand to make him look ridiculous. Mencken’s obituary of Mencken in the American Mercury, titled, To Expose a Fool, must surely rank as one of the most vindictive of all time. A few excerpts will serve to convey the author’s unrelenting malice:

He was the most sedulous flycatcher in American history, and by long odds the most successful…

If the fellow was sincere, then so was P.T. Barnum. The word is disgraced and degraded by such uses. He was, in fact, a charlatan, a mountebank, a zany without any shame or dignity. What animated him from end to end of his grotesque career was simply ambition–the ambition of a common man to get his hand upon the collar of his superiors, or, failing that, to get his thumb into their eyes…

What moved him, at bottom, was simply hatred of city men who had laughed at him so long, and brought him at last to so tatterdemalion an estate. He lusted for revenge upon them…

He went far beyond the bounds of any merely religious frenzy, however inordinate. When he began denouncing the notion that man is a mammal even some of the hinds at Dayton were agape. And when, brought upon Darrow’s cruel hook, he writhed and tossed in a very fury of malignancy…

Upon that hook, in truth, Byran committed suicide, as a legend as well as in the body. He staggered from the rustic court ready to die, and he staggered from it ready to be forgotten, save as a character in a third-rate farce, witless and in execrable taste…

The evil that men do lives after them. Bryan, in his malice, started something that will not be easy to stop. In ten thousand country town his old heelers, the evangelical pastors, are propagating his gospel, and everywhere the yokels are ready for it…

Bryan came very near being President of the United States. In 1896, it is possible, he was actually elected. He lived long enough to make patriots thank the inscrutable gods for Harding, even for Coolidge. Dulness has got into the White House, and the smell of cabbage boiling, but there is at least nothing to compare to the intolerable buffoonery that went on in Tennessee. The President of the United States doesn’t believe that the earth is square, and that witches should be put to death, and that Jonah swallowed the whale…

Such is Bryan’s legacy to his country. He couldn’t be President, but he could at least help magnificently in the solemn business of shutting off the presidency from every intelligent and self-respecting man.

American Mercury, October 1925, pp. 158-160.

Should we trust such a malicious source?

Bombshell Number Three: Mencken’s views on how evolution should be taught in schools were virtually the same as those of the modern Intelligent Design movement

|

H. L. Mencken, like William Jennings Bryan and like the modern-day Intelligent Design movement, believed that the theory of evolution should be taught in schools not as a fact but as an hypothesis, and that the scientific arguments for and against the theory should be presented in a fair and balanced manner. Statue of Themis, the Greek goddess of justice, holding the scales of justice in her right hand. Chuo University, Japan. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

My third “bombshell” – which I stumbled upon quite by accident, while conducting my research on the Internet – is that Mencken’s views on how evolution should be taught in schools were virtually the same as those of the modern Intelligent Design movement: Mencken believed that the arguments in its favor should be presented, along with the scientific objections to it. Here is an excerpt from a report in the Baltimore Evening Sun (June 15, 1925), titled, The Tennessee Circus, which was Mencken’s very first report discussing the upcoming Scopes Trial, which commenced the following month. In his article, Mencken contrasts two different approaches to Scripture: that of evangelical Christians, who are committed to upholding its literal accuracy in every verse, and that of churches which set up an authority, which is competent to officially determine the meaning of difficult or controverted passages. In the latter group, Mencken includes not only the Catholic Church, but also the Anglican, Greek Orthodox, and Presbyterian churches. Mencken describes these churches as “authoritarian” and praises the way in which they are handling the current controversy, by teaching evolution not as a fact, but as a hypothesis accepted by most scientists, and then presenting the arguments for evolution and the difficulties with the theory – an approach which Mencken hails as “an intelligent attitude”:

…[T]he current discussion of the Tennessee buffoonery, in the Catholic and other authoritarian press, is immensely more free and intelligent than it is in the evangelical Protestant press. In such journals as the Conservator, the new Catholic weekly, both sides are set forth, and the varying contentions are subjected to frank and untrammeled criticism. Canon de Dorlodot whoops for evolution; Dr. O’Toole denounces it as nonsense. If the question were the Virgin Birth, or the apostolic succession, or transubstantiation, or even birth control, the two antagonists would be in the same trench, for authority binds them there. But on the matter of evolution authority is silent, and so they have at each other in the immemorial manner of theologians, with a great kicking up of dust.

The Conservator itself takes no sides, but argues that Evolution ought to be taught in the schools – not as incontrovertible fact but as a hypothesis accepted by the overwhelming majority of enlightened men. The objections to it, theological and evidential, should be noted, but not represented as unanswerable.

Obviously, this is an intelligent attitude. Equally obviously, it is one that the evangelical brethren cannot take without making their position absurd. For weal or for woe, they are committed absolutely to the literal accuracy of the Bible; they base their whole theology upon it. Once they admit, even by inference, that there may be a single error in Genesis, they open the way to an almost complete destruction of that theology.

And here is the official position of the Intelligent Design movement’s Discovery Institute on the theory of evolution in America’s public schools:

What does the Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture recommend for science education curriculum?

As a matter of public policy, Discovery Institute opposes any effort to require the teaching of intelligent design by school districts or state boards of education. Attempts to mandate teaching about intelligent design only politicize the theory and will hinder fair and open discussion of the merits of the theory among scholars and within the scientific community. Furthermore, most teachers at the present time do not know enough about intelligent design to teach about it accurately and objectively.

Instead of mandating intelligent design, Discovery Institute seeks to increase the coverage of evolution in textbooks. It believes that evolution should be fully and completely presented to students, and they should learn more about evolutionary theory, including its unresolved issues. In other words, evolution should be taught as a scientific theory that is open to critical scrutiny, not as a sacred dogma that can’t be questioned.

Discovery Institute believes that a curriculum that aims to provide students with an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of neo-Darwinian and chemical evolutionary theories (rather than teaching an alternative theory, such as intelligent design) represents a common ground approach that all reasonable citizens can agree on.

Bombshell Number Four: Although Mencken assisted the defense case, he actually agreed with Bryan that the people of Tennessee had the right to set the science curriculum for government-funded schools, and that teachers should follow it

|

The Tennessee State Capitol in Nashville, Tennessee. Image courtesy of Kaldari and Wikipedia.

The fourth “bombshell” I discovered was that despite Mencken’s eager involvement with the defense case in the Scopes Trial, he actually disagreed with the ACLU’s position in bringing the case against the state of Tennessee. The ACLU, in taking on the Scopes trial, wanted a case to establish, as they saw it, the unconstitutional nature of a ban on the teaching of evolutionist theory. The ACLU felt that academic freedom and integrity, as well as the separation of church and state, were at stake. It wanted to make the Scopes case the centerpiece of its campaign for freedom of speech. As Roger Baldwin, the founder of the ACLU, put it: “We shall take the Scopes case to the United States Supreme Court if necessary to establish that a teacher may tell the truth without being thrown in jail.”

Mencken, on the other hand, thought that Tennessee’s ban was perfectly constitutional, and that the citizens of each state had every right to set their own public school curriculum. On this point, he was totally in agreement with William Jennings Bryan, who told the West Virginia Legislature in 1923: “The hand that writes the paycheck rules the school.”

Tennessee vs. Truth: The key issue at stake in the Scopes trial, for the ACLU

An unsigned editorial in The Nation (July 8, 1925, p. 58), titled “Tennessee vs. Truth,” went straight to the heart of the matter, in its first paragraph: should the content of a state’s science curriculum be determined by popular vote or by scientists, who acquire knowledge using the scientific method?

When the prosecution of John T. Scopes, teacher of Biology in the Dayton high school is begun on July 10, it ought to be cried out by the court clerk as the State of Tennessee vs. Truth. For the trial brings to a head the attempt of a great commonwealth to determine science by popular vote, to establish truth by fiat instead of study, research and experiment.

There is no doubt that this was the position endorsed by the ACLU: the academic freedom of science teachers to teach the truth, in accordance with the scientific method, was paramount. But this was not Mencken’s view.

Mencken believed the recently passed 1925 Butler Act (which forbade the teaching of human evolution in public high schools) to be fully constitutional, and he told Bryan as much when he first met him in person, on July 9, 1925. What’s more, in an article for The Nation (July 1, 1925), written just nine days before the trial began, he argued that high school teachers were paid pedagogues, who should be content to teach whatever their state required them to teach.

Professor Doug Linder, of the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law, expressed his puzzlement at Mencken’s decision to assist the defense case in the Scopes Trial, which was trying to have the Butler Act overturned as unconstitutional, in a 2004 essay on H. L. Mencken:

Mencken’s active interest in the defense case is surprising in light of his views published in The Nation just a week before the Scopes trial began. In his Nation column, he insisted, “No principle is at stake at Dayton save the principle that school teachers, like plumbers, should stick to the job that is set before them, and not go roving around the house, breaking windows, raiding the cellar, and demoralizing children.” The issue of free speech was “irrelevant”: “When a pedagogue takes his oath of office, he renounces his right to free speech quite as certainly as a bishop does, or a colonel in the army, or an editorial writer of a newspaper. He becomes a paid propagandist of certain definite doctrines… and every time he departs from them deliberately he deliberately swindles his employers.” Mencken argued that states had the right to make curricular choices based what might have the greatest “utility” for students. “What could be of greater utility to the son of a Tennessee mountaineer,” he asked, “than an education making him a good Tennesseean, content with his father, at peace with his neighbors, dutiful to the local religion, and docile under the local mores?”

After Mencken stepped off the train in Dayton one hot afternoon in early July, he ran into William Jennings Bryan and — to Bryan’s delight — reaffirmed his printed opinion that the Butler Act was constitutional. The Commoner announced to a crowd that gathered around the two men as they chatted, “This Mencken is the best newspaperman in the country!” It was an opinion that Bryan would not hold for long…

The tone of Mencken’s reports soon changed as the trial began.

If we examine Mencken’s column for The Nation (July 1, 1925), we can see that in addition to arguing that teachers were paid to teach what the state required them to teach, he also contended that the people of the state of Tennessee, through their elected representatives, had a perfect right to decree what should or should not be included in their state’s high school curriculum, and that it was quite appropriate for them to make this decision on the basis of what was likely to have the greatest “utility” for students, as future citizens of that state. Mencken forcefully rejected the notion that “some mysterious and vastly important principle is at stake at Dayton” – “Tell it to the marines!” he scoffed:

So, now, in Tennessee, where a rural pedagogue stands arraigned before his peers for violating the school law. At bottom, a quite simple business. The hinds of the State, desiring to prepare their young for life there, set up public schools. To man those schools they employ pedagogues. To guide those pedagogues they lay down rules prescribing what is to be taught and what is not to be taught. Why not, indeed? How could it be otherwise? Precisely the same custom prevails everywhere else in the world, wherever there are schools at all. Behind every school ever heard of there is a definite concept of its purpose of the sort of equipment it is to give to its pupils. It cannot conceivably teach everything; it must confine itself by sheer necessity to teaching what will be of the greatest utility, cultural or practical, to the youth actually in hand. Well, what could be of greater utility to the son of a Tennessee mountaineer than an education making him a good Tennesseean, content with his father, at peace with his neighbors, dutiful to the local religion, and docile under the local mores?

That is all the Tennessee anti-evolution law seeks to accomplish. It differs from other regulations of the same sort only to the extent that Tennessee differs from the rest of the world. The State, to a degree that should be gratifying, has escaped the national standardization. Its people show a character that is immensely different from the character of, say, New Yorkers or Californians. They retain, among other things, the anthropomorphic religion of an elder day. They do not profess it; they actually believe in it. The Old Testament, to them, is not a mere sacerdotal whizz-bang, to be read for its pornography; it is an authoritative history, and the transactions recorded in it are as true as the story of Barbara Frietchie, or that of Washington and the cherry tree, or that of the late Woodrow’s struggle to keep us out of the war. So crediting the sacred narrative, they desire that it be taught to their children, and any doctrine that makes game of it is immensely offensive to them. When such a doctrine, despite their protests, is actually taught, they proceed to put it down by force.

Is that procedure singular? I don’t think it is. It is adopted everywhere, the instant the prevailing notions, whether real or false, are challenged. Suppose a school teacher in New York began entertaining his pupils with the case against the Jews, or against the Pope. Suppose a teacher in Vermont essayed to argue that the late Confederate States were right, as thousands of perfectly sane and intelligent persons believe that Lee was a defender of the Constitution and Grant a traitor to it. Suppose a teacher in Kansas taught that prohibition was evil, or a teacher in New Jersey that it was virtuous. But I need not pile up suppositions. The evidence of what happens to such a contumacious teacher was spread before us copiously during the late uproar about Bolsheviks. And it was not in rural Tennessee but in the great cultural centers which now laugh at Tennessee that punishments came most swiftly, and were most barbarous. It was not Dayton but New York City that cashiered teachers for protesting against the obvious lies of the State Department.

Yet now we are asked to believe that some mysterious and vastly important principle is at stake at Dayton that the conviction of Professor Scopes will strike a deadly blow at enlightenment and bring down freedom to sorrow and shame. Tell it to the marines! No principle is at stake at Dayton save the principle that school teachers, like plumbers, should stick to the job that is set before them, and not go roving about the house, breaking windows, raiding the cellar, and demoralizing the children. The issue of free speech is quite irrelevant. When a pedagogue takes his oath of office, he renounces his right to free speech quite as certainly as a bishop does, or a colonel in the army, or an editorial writer on a newspaper. He becomes a paid propagandist of certain definite doctrines and attitudes, mainly determined specifically and in advance, and every time he departs from them deliberately he deliberately swindles his employers…

A pedagogue, properly so called and a high-school teacher in a country town is properly so called is surely not a searcher for knowledge. His job in the world is simply to pass on what has been chosen and approved by his superiors…

Liberty of teaching begins where teaching ends.

The paradox: Mencken was an ardent champion of states’ rights, yet he did everything in his power to oppose the state of Tennessee in its attempt to ban the teaching of human evolution as a scientific fact

The paradox that confronts historians of the Scopes trial is that despite the democratic views expressed above on the right of each state to set its own school curriculum, Mencken also put forward a frankly elitist argument against majority rule in his now-classic article, Homo Neanderthalensis (The Baltimore Evening Sun, June 29, 1925):

Every step in human progress, from the first feeble stirrings in the abyss of time, has been opposed by the great majority of men. Every valuable thing that has been added to the store of man’s possessions has been derided by them when it was new, and destroyed by them when they had the power. They have fought every new truth ever heard of, and they have killed every truth-seeker who got into their hands.

The so-called religious organizations which now lead the war against the teaching of evolution are nothing more, at bottom, than conspiracies of the inferior man against his betters. They mirror very accurately his congenital hatred of knowledge, his bitter enmity to the man who knows more than he does, and so gets more out of life. Certainly it cannot have gone unnoticed that their membership is recruited, in the overwhelming main, from the lower orders — that no man of any education or other human dignity belongs to them. What they propose to do, at bottom and in brief, is to make the superior man infamous — by mere abuse if it is sufficient, and if it is not, then by law.…

The inferior man’s reasons for hating knowledge are not hard to discern. He hates it because it is complex — because it puts an unbearable burden upon his meager capacity for taking in ideas. Thus his search is always for short cuts. All superstitions are such short cuts. Their aim is to make the unintelligible simple, and even obvious…

The popularity of Fundamentalism among the inferior orders of men is explicable in exactly the same way…

What all this amounts to is that the human race is divided into two sharply differentiated and mutually antagonistic classes, almost two genera — a small minority that plays with ideas and is capable of taking them in, and a vast majority that finds them painful, and is thus arrayed against them, and against all who have traffic with them. The intellectual heritage of the race belongs to the minority, and to the minority only. The majority has no more to do with it than it has to do with ecclesiastic politics on Mars.

So, how do we account for the fact that in his series of articles for the Baltimore Evening Sun, Mencken was blisteringly critical of the proposal to prohibit the teaching of human evolution in Tennessee’s high schools, arguing that the content of the science curriculum should not be decided by a majority vote, but by the intelligentsia, even though he had argued for the opposite position in The Nation on July 1, 1925? It might be tempting to suppose that Mencken had a sudden change of heart – but the chronology of Mencken’s articles refutes that hypothesis: Mencken’s elitist article for the Baltimore Evening Sun, Homo neanderthalensis, was written in June 29, two days before his article for The Nation on July 1.

Will the real Mencken please step forward?

Mencken provides some clues that reconcile the apparent contradiction in his attitudes, in two articles for the Baltimore Evening Sun. In his article of July 27, 1925, he explained his position as follows:

When I first encountered him [on July 9 – VJT], on the sidewalk in front of the Hicks brothers law office, the trial was yet to begin, and so he was still expansive and amiable. I had printed in the Nation, a week or so before, an article arguing that the anti-evolution law, whatever its unwisdom, was at least constitutional — that policing school teachers was certainly not putting down free speech. The old boy professed to be delighted with the argument, and gave the gaping bystanders to understand that I was a talented publicist. In turn I admired the curious shirt he wore — sleeveless and with the neck cut very low. We parted in the manner of two Spanish ambassadors.

Another clue can be found in his article of July 20, he chides the educated minority of Tennesseans who did nothing to oppose the bill until it was too late:

But what of the rest of the people of Tennessee? I greatly fear that they will not attain to consolation so easily. They are an extremely agreeable folk, and many of them are highly intelligent. I met men and women — particularly women — in Chattanooga who showed every sign of the highest culture. They led civilized lives, despite Prohibition, and they were interested in civilized ideas, despite the fog of Fundamentalism in which they moved. I met members of the State judiciary who were as heartily ashamed of the bucolic ass, Raulston, as an Osler would be of a chiropractor. I add the educated clergy: Episcopalians, Unitarians, Jews and so on — enlightened men, tossing pathetically under the imbecilities of their evangelical colleagues. Chattanooga, as I found it, was charming, but immensely unhappy.

What its people ask for — many of them in plain terms — is suspended judgment, sympathy, Christian charity, and I believe that they deserve all these things. Dayton may be typical of Tennessee, but it is surely not all of Tennessee. The civilized minority in the State is probably as large as in any other Southern State. What ails it is simply the fact it has been, in the past, too cautious and politic — that it has been too reluctant to offend the Fundamentalist majority. To that reluctance something else has been added: an uncritical and somewhat childish local patriotism. The Tennesseeans have tolerated their imbeciles for fear that attacking them would bring down the derision of the rest of the country. Now they have the derision, and to excess — and the attack is ten times as difficult as it ever was before.

A final clue can be provided in his article, Aftermath of September 14, 1925:

The way to deal with superstition is not to be polite to it, but to tackle it with all arms, and so rout it, cripple it, and make it forever infamous and ridiculous. Is it, perchance, cherished by persons who should know better? Then their folly should be brought out into the light of day, and exhibited there in all its hideousness until they flee from it, hiding their heads in shame.

True enough, even a superstitious man has certain inalienable rights. He has a right to harbor and indulge his imbecilities as long as he pleases, provided only he does not try to inflict them upon other men by force. He has a right to argue for them as eloquently as he can, in season and out of season. He has a right to teach them to his children. But certainly he has no right to be protected against the free criticism of those who do not hold them. He has no right to demand that they be treated as sacred. He has no right to preach them without challenge. Did Darrow, in the course of his dreadful bombardment of Bryan, drop a few shells, incidentally, into measurably cleaner camps? Then let the garrisons of those camps look to their defenses. They are free to shoot back. But they can’t disarm their enemy.

I would like to propose that what Mencken might have said in his own defense, were he alive today and being cross-examined about his apparently contradictory statements, is this:

Each state has a perfect right to set its own school curriculum. But the educated minority of people living in that state also have the right to publicly oppose measures initiated by a government – including laws drafted for the state’s representatives to vote on – which set back the cause of scientific progress. Indeed, they have the duty to do so. What’s more, they have every right to publicly ridicule the simpletons who put forward these laws, and expose the absurdities of their religious beliefs. People deserve a certain measure of respect; erroneous beliefs deserve none.

I, as a public citizen who cares deeply about the truth, have the right to assist this educated minority by using my pen to expose the ignorant majority to unrelenting ridicule, in order to persuade their leaders that passing bills that would prevent science teachers from teaching the theory of evolution as I believe it should be taught. Once the vote is taken by a state’s political representatives, it becomes settled law. But until then I have every right to fight it tooth and nail – and even afterwards, I reserve my right to resort to ridicule and invective, in the hope of persuading that state’s leaders to repeal that law.

Bombshell Number Five: There really was a conspiracy by Mencken and other journalists to get Bryan

|

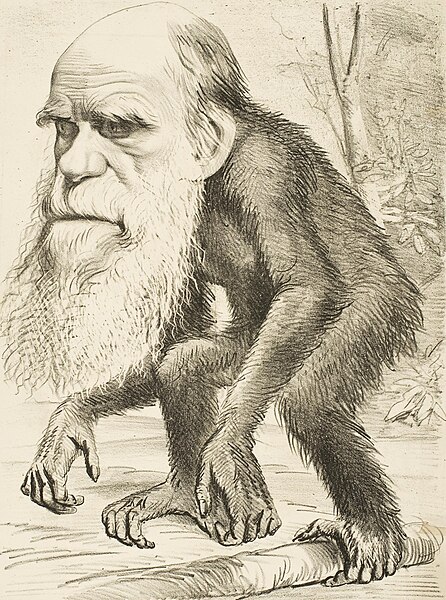

H. L. Mencken proposed that the defense lawyers in the Scopes trial should try to “make a monkey out of Bryan” and expose him to public ridicule. The image above, titled “A Venerable Orang-outang”, is a caricature of Charles Darwin as an ape (not a monkey), published in The Hornet, a satirical magazine, 22 March 1871. Image courtesy of University College London Digital Collections (18886) and Wikipedia.

Mencken’s advice to the Scopes trial defense team: “This isn’t about Scopes. Let’s get Bryan!”

Mencken did not cover the Scopes trial as a detached observer. As biographer Marion Elizabeth Rodgers notes in her book, Mencken: The American Iconoclast (Oxford University Press, 2005; paperback, 2007), Mencken had a very personal stake in the trial:

Throughout the decade [the 1920s – VJT] Mencken had taken it upon himself to champion the cause of the “beleaguered cities” against the “barbaric yokels” from the hinterland. One of the reasons for Mencken’s hostility towards agrarian America was its ties to Protestant Fundamentalism, which he considered anathema to the nation’s well-being. He went to Dayton as a combatant in what he sincerely took to be a a struggle of civilization and science against bigotry and superstition. (p. 273)

In her biography, Rodgers reveals that Mencken assisted the defense team in formulating their strategy at the Scopes trial. Mencken adopted a very aggressive approach from the outset: it was he who suggested that the lawyers should go after Bryan, with the aim of making him look ridiculous:

Hays’ actions on behalf of free speech had made him a key figure at the ACLU. In 1925, the organization was only five years old, and was seeking its first court victory. Hays called on Mencken to help prepare their strategy.

The aim of Darrow and his team was to have Scopes acquitted, but Mencken disagreed. The best way to handle the case, he argued, was to “convert it into a headlong assult on Bryan.” It was he who was the international figure, “not that poor worm of a schoolmaster.” Mencken proposed that the lawyers put Bryan on the stand if possible, “to make him state his barbaric credo in plain English, and to make a monkey of him before the world.” The team agreed, although Hays still insisted Scopes could be acquitted.As the skirmish began, newspapers promised that the trial would be a world sensation. (p. 272)

In her biography, Rodgers also reveals that Mencken deliberately stereotyped the people of Dayton, Tennessee:

In an effort to prove to Mencken and the other journalists that their reporting was biased, that within those same hills there also existed educated circuit preachers, drugstore owner Fred Robinson made a special effort to introduce out-of-state reporters to a highly educated minister. The New York Times subsequently wrote in amazement of the Tennessee mountain man who had, along with his old clothes and polished boots, a scholar’s knowledge of Greek and Hebrew as well as Darwin’s Origin of Species. But to Robinson’s dismay, “Mencken kept with the hillbilly story of the Holy Rollers.” (p. 278)

…”I have met no educated man who is not ashamed of the ridicule that has fallen upon the state,” reflected Mencken. The civilized minority had known for years what was going on in the hills, wrote Mencken: “They knew what country preachers [had] rammed and hammered into yokel skulls.” Now Tennessee was paying the price. (p. 281)

In spite of the trial’s lack of dignity, the columnist asked that his readers “not make the colossal mistake” of viewing it as “a trivial farce.” But the next American who finds himself with an idle million on his hands, Mencken proposed, should dedicate it to civilizing Tennessee, “a sort of Holy Land for imbeciles.” (p. 282)

What disturbed the local townspeople of Dayton most was to be portrayed as religious fanatics. While many of the population admitted to being conservative Christians, the residents disliked being described as mountaineers. Two who fell into this category were college graduates from northern Pennsylvania. Others gave interviews, only to find that their speech had been liberally sprinkled in print with words like “hain’t” and “sech.”

“Some of the newspaper correspondents attending the trial have apparently lost no opportunity for exaggeration if not downright misrepresentation,” complained the Chattanooga Times. It was noted that in their thirst for local color, “they have seized upon the most narrow, ignorant, backward aspects of the community and harped upon them as though they were representative… Such writing is obviously unfair and unjust and beneath the ethics of anybody who adheres to an enlightened code of intellectual honesty.”

Locally, much of the unfairness was blamed on Mencken. To this day, Mencken’s name is mentioned in Dayton with contempt; in 1925, he was anointed “the stinker.” (“Mr. Mencken did not degenerate from an ape,” one local said, “but from an ass.”) It was not, as Mencken supposed, his description of the Holy Roller meeting that caused the most fury, but his caricatures of the “Babbitts” and “backward” locals, “hillbillies,” “yaps,” “yokels,” “peasants” and mountaineers from the hills of East Tennessee that infuriated citizens who prided themselves on their intelligence…

“In a way it was Mencken’s show,” John Scopes recalled in 1967. “In the public mind today, a mention of the Dayton trial more likely evokes Mencken than it does me. His biting commentary on the Bible Belt and the trial itself was one of the highlights of the entire event.” Yet even Scopes disagreed with Mencken’s portrayal of the Dayton townsfolk as “morons”; many were his friends. Looking back at the trial years later, Scopes dismissed Mencken as “a sensationalist.” (pp. 287-288)

Rodgers’ unflattering description of Mencken’s reporting of the Scopes trial is confirmed by Lawrance M. Bernabo and Celeste Michelle Condit in their essay, “Two Stories of the Scopes Trial: Legal and Journalistic Articulations of the Legitimacy of Science and Religion” (in Popular Trials: Rhetoric, Mass Media, and the Law, edited by Robert Hariman, University of Alabama Press, 1990, pp. 76-77). After narrating how the press attempted to delegitimatize the outcome of the Scopes trial by ridiculing the trial process, ridiculing Bryan, and ridiculing the people of Tennessee, Bernabo and Condit single out Mencken for his biased reporting on the Scopes trial:

The master of vituperative, hopwever, was the literary gadfly, H. L. Mencken, for whom the “hellawful” South had been the subject of a verbal campaign since the 1920 publication of his most scathing essay, “The Sahara of the Bozart,” which decried the literary poverty of the postbellum South…

Mencken’s syndicated columns for the Baltimore Evening Sun from Dayton drew vivid caricatures of the “backward” local populace, referring to the people of Rhea county as “Babbits,” “morons,” “peasants,” “hillbillies,” “yaps” and “yokels.”…

…Mencken’s portrayals, however sustained and excessive, were nonetheless reflective of the general direction of the press coverage as a whole. They also reveal the fundamental “lines of battle” drawn in the socio-political war.

The entire press gallery was trying to make Bryan and the people of Tennessee look ridiculous

In their essay, “Two Stories of the Scopes Trial: Legal and Journalistic Articulations of the Legitimacy of Science and Religion” (in Popular Trials: Rhetoric, Mass Media, and the Law, edited by Robert Hariman, University of Alabama Press, 1990), Lawrance M. Bernabo and Celeste Michelle Condit relate how national press coverage of the Scopes trial was skewed from the outset, with the aim of making Bryan and the people of Tennessee look ridiculous, pathetic and behind the times:

The dominance of ridicule as the primary mood and theme in the working press served to delegitimate the trial even before it began. Anticipating that Scopes would be found guilty, the working press fitted Scopes for martyrdom and assailed the proponents of “religion.”…

The efforts at ridicule were widespread and colorful. Time‘s initial coverage of the trial focused on Scopes as “the fantastic cross between a circus and a holy war.” Life shared the portrayal, adorning its masts with monkeys reading books, and proclaiming that “the whole matter is something to laugh about.” Hosts of cartoonists added their own portrayals to the attack. Both Life and Literary Digest ran compilations of jokes and humorous observations garnered from newspapers around the country. Overwhelmingly, the butt of these jokes were those aligned with the prosecution: Bryan, the city of Dayton, the state of Tennessee, and the entire South, as well as Fundamentalist Christians and anti-evolutionists…

Delegitimation of the outcome of the trial was thus accomplished through a general ridicule of the trial. It was accompanied, however, by fairly strong ridicule of the location and agents of the trial. Attacks on Bryan were predictably frequent and nasty. For example, Life awarded Bryan its brass medal of the Fourth Class, for having “successfully demonstrated that by the alchemy of ignorance hot air may be transmuted into gold, and that the Bible is infallibly inspired except where it differs from him on the question of wine, women and wealth.” The medal featured a caricature of an open-mouthed Bryan with a “Blah” sounding forth, with a flip side showing Bryan with an arm around an ape under the legend “Pals.” Such attacks not only delegitimated the trial, but also served to reverse the rhetorical impact of the trial, anticipating Darrow’s ridicule of Bryan in cross-examination…

The most widespread form of this ridicule was directed at the inhabitants of Tennessee. By portraying the state as an “unfit” place and its citizens and courts as unfit agents, the journalists further created a presumption both against the trial and against the collection of interests represented by the prosectution. Life described Tennessee as “not up-to-date in its attitudes to such things as evolution.” Time related Bryan’s arrival in town with the disparaging comment, “The populace, Bryan’s to a moron, yowled a welcome.” Throughout its coverage, the magazine continued this bias, covering the urban-rural tensions in detail, while reducing the issue of constitutionality to a single unsubstantive comment. The press as a whole gave great attention to a wide variety of incidents that further substantiated this image. For example, they reported fully the case of the “free thinker” who was held by the town’s sole policeman because “He wasn’t talking right, and I was afraid some of the boys take hold of him.” The free speaker was held for disturbing the peace. Those reporters who arrived in Dayton only to discover that the townsfolk were relatively open-minded, simnply shifted the focus of their attacks to the Holy Rollers gathered in the hills outside of Dayton or the state of Tennessee as a whole…

The attack on the “locals” articulated the central motive behind the national press’s tendency to side against the judge, the prosecution, and religious fundamentalism. The national press simply did not share the native discourse of the Tennesseans. To begin with, they were not submerged in a naturalized vocabulary of Christianity; the derogation of foreign ways is an all too normal response to difference. In addition, they were highly sympathetic to the case of science. As a national press they had recently come to honor Darrow’s values – “truth” and “objectivity” – as part of their credo. Finally, and crucially, their very survival was dependent on upholding national discourses over local ones; a national press can only succeed where there is a national idiom. No wonder then that the journalists articulated their preference against “the local.”

The depiction of the scene of the trial and the home ground of the prosecution as local rather than national and as backward rather than progressive vividly reconstructed the religious case as a subjective and limited one, pitted against the “universal” political value of progress. The fear of being caught in “ignorance” – outside of progress – was pervasive. The fervor of the concern with intellectual progress is evident not only in the news accounts, but in the two sorts of stories that responded to these accounts. Southern papers fretted about how their religion was being portrayed, the Savannah News asking “Is it Genesis or Tennessee on trial in Dayton?” The Southerners did not disown the value of (intellectual) progress, but rather wished to deny their own failure to meet that standard. A second reflection of the widespread endorsement of “education” and “progress” over “backwardness” is found in the sensitive American reaction to the European press. Foreign reporters indicated that European reporters were amazed that an American state would attempt to prevent the teaching of evolution, a matter that had been settled in Britain “long ago.” Even the London Times characterized the trial as an attempt by the defense to estanlish “Darrow and Malone’s Dayton University.” …

(“Two Stories of the Scopes Trial: Legal and Journalistic Articulations of the Legitimacy of Science and Religion” by Lawrance M. Bernabo and Celeste Michelle Condit, in Popular Trials: Rhetoric, Mass Media, and the Law, edited by Robert Hariman, University of Alabama Press, 1990, pp. 74-78.)

Further evidence of systematic press bias in the reportage of the Scopes trial can be found in Professor Gerald Priest’s essay, William Jennings Bryan and the Scopes Trial:

According to early Bryan biographer J. C. Long, most of the reporters were so biased against Bryan and fundamentalism that their editorials were an unofficial witness for Darrow and the defense. They made it appear as though Bryan and his “shopworn” principles were on trial, instead of Scopes.(61) Warren Allem quotes from an editorial in The New Republic that journalists

have schemed and labored to present the court proceedings to American opinion in the guise of a melodrama in which William J. Bryan, the Attorney General, and Judge Raulston are portrayed as reprobates who are conspiring to convict and punish an innocent man, and deprive the jury and the American people of the evidence in the case. What they have actually succeeded in doing is to cheapen not only the trial but the issue by subordinating both of them to the exigencies of theatrical newspaper publicity. (62)

Footnotes

61. J. C. Long, Bryan, The Great Commoner (New York: D. Appleton, 1928), p. 381. See also, the comments of Henry Fairfield Osborn, whose hastily written book just prior to Dayton excoriated the religiously “fanatical” and scientifically “stone-deaf” Bryan as the man on trial (cited in Larson, Summer for the Gods, p. 113).

62. Warren Allem, “Backgrounds of the Scopes Dayton Trial at Tennessee” (M.A. thesis, University of Tennessee, 1959), p. 30.

Bombshell Number Six: The Catholic Church’s position on evolution was very similar to that of Mencken

|

In his reportage of the Scopes trial, H. L. Mencken was careful to attack only one group of Christians: the Fundamentalists. What he neglected to mention, however, was that the position of Catholics on evolution was virtually the same as that of the Fundamentalists whom he derided. In his 1880 encyclical Arcanum on Christian marriage, Pope Leo XIII had written, “We call to mind facts well-known to all and doubtful to no-one: after He formed man from the slime of the earth on the sixth day of creation, and breathed into his face the breath of life, God willed to give him a female companion, whom He drew forth wondrously from the man’s side as he slept.” The image above is a portrait of Pope Leo XIII. Image courtesy of Library of Congress and Wikipedia.

My sixth bombshell was that Mencken displayed an outrageous double standard in his treatment of the various Christian denominations in his reporting on the Scopes trial. Mencken carefully refrained from criticizing the larger Christian churches, such as the Catholic Church, America’s largest Christian denomination (numbering about 17% of the population at that time), even going so far as to praise the “intelligent attitude” of the Catholic Church towards evolution, along with “[t]he Anglican, Orthodox, Greek and various other churches, including the Presbyterian” in a report for the Baltimore Evening Sun (June 15, 1925). Mencken chose to focus his attacks entirely on “evangelicals” and “fundamentalists” such as William Jennings Bryan, despite the fact that the Catholic Church’s position on evolution and the miracles recorded in Genesis and the rest of the Bible was virtually the same as Bryan’s.

In his reporting on the Scopes trial, Mencken repeatedly referred to the people of Dayton, Tennessee as “fundamentalists,” mocking the “fundamentalist rubbish” spouted by the prosecution in the Scopes trial, and deriding Bryan as a “fundamentalist pope” who “hates and fears” science, in his article for the Baltimore Evening Sun dated July 16, 1925. However, a close examination of the evidence revela that Bryan’s position on evolution and on Biblical miracles (which Mencken deemed incompatible with modern science) was virtually with that of the Catholic Church, on matters such as the age of the earth (both Bryan and the Catholic Church allowed that it might be millions of years old), animal and human evolution (Bryan, like the Catholic Church, allowed for the possibility of the former but not the latter), the reality of a universal Flood (Bryan rejected Archbishop Ussher’s traditional chronology, which placed the occurrence of the Flood at around 4,300 years ago, while the Catholic Church allowed that the Flood might have occurred much earlier, and that while it wiped out all humans living at the time, except for Noah and his family, it was probably not global), Joshua’s miracle of the sun (the literal historicity of which was upheld by both Bryan and the Catholic Church), and the historicity of the Biblical account of Jonah and the whale (which was vehementaly defended by the Catholic Church).

The Age of the Earth

The records of the Scopes trial show that Bryan was an old-earth creationist who rejected the view that the days in Genesis were 24-hour days, declared that the Earth was “much older” than several thousand years, and even acknowledged that the creation “might have continued for millions of years.” The Catholic Church left the age of the Earth an open question for the faithful: the Pontifical Biblical Commission, in its response on Genesis, dated 30 June 1909, stated that in the “designation and distinction of six days, with which the account of the first chapter of Genesis deals, the word “day” (dies) can be assumed either in its proper sense as a natural day, or in the improper sense of a certain space of time.” On this topic, said the Commission, “there can be free disagreement among exegetes.”

Animal and human evolution

While Bryan ridiculed the idea that all animals sprang from a common stock in his book, In His Image (Fleming H. Revell Company, New York, 1922, p. 103), he nevertheless allowed that “evolution in plant life and in animal life up to the highest form of animal might, if there were proof of it, be admitted without raising a presumption that would compel us to give a brute origin to man” (ibid., pp. 103-104). For Bryan, however, it was an essential part of Christian belief that man had been specially created in the image and likeness of God. This was virtually identical to the position of the Catholic Church at that time. In 1860, a meeting of German Catholic bishops at the Provincial Council of Cologne, which was convoked by Cardinal Joannes von Geissel, had left open the possibility that animals may have evolved naturally, while unequivocally condemning the hypothesis of a “spontaneous” (i.e., purely natural) evolution for the human body, and insisting that “our first parents were formed immediately by God.” The decrees of the Council were subsequently recognized by the Holy See in 1861 and praised (but not officially promulgated) by Pope Pius IX in 1862. Subsequent Popes also upheld the special creation of man: in 1880, Pope Leo XIII, in his encyclical Arcanum on Christian marriage, alluded to “facts well-known to all and doubtful to no-one: after He formed man from the slime of the earth on the sixth day of creation, and breathed into his face the breath of life, God willed to give him a female companion, whom He drew forth wondrously from the man’s side as he slept.” Under Pope Pius X, the Pontifical Biblical Commission, in its response on the book of Genesis on 30 June 1909, officially declared “the special creation of man,” “the formation of the first woman from the first man,” and “the transgression of the divine command” by “our first parents” through “the devil’s persuasion under the guise of a serpent” to be facts, where “the literal and historical sense” of the Genesis narrative could not be called into question. It is true that special transformism, or the theory that God had supernaturally transformed the body of a human-like creature that had evolved naturally into the human body of Adam, was never officially excluded by the Church, but in 1925, it was still a very daring theological opinion – and in any case, it was incompatible with Darwinism, since it posited a miraculous intervention by God, when making the human body. In any case, the hypothesis of special transformism was not openly endorsed by any Catholic theologian until 1931, six years after the Scopes Trial, with the publication of Fr. Ernest Messenger’s Evolution and Catholic Theology: The Problem of Man’s Origin. And it was only in 1950 that Pope Pius XII, in his encyclical Humani Generis, declared licit the hypothesis that the human body had evolved, while insisting that the human soul was a Divine creation and that there had only been one original couple (Adam and Eve) at the beginning of human history.

The Catholic Encyclopedia, in its article on Creation, declared that “the first plant, fish, bird, and beast” had “been evolved out of the potency of matter without parentage”, and insisted that “God must have been the sole efficient cause… of the organization requisite, and hence may strictly be said to have formed such pairs, and in particular the human body, out of the pre-existent matter”:

Though God can operate as He does in the creative act, without the cooperation of the creature, it is absolutely impossible for the creature to elicit even the smallest act without the co-operation of the Creator. Now the Divine Administration includes this and more, two things, namely, as regards the present subject. The one is the constant order, the natural laws of the universe. Thus, e.g., that all living things should be ordinately propagated by seed belongs to the Divine Administration. The second, which may be called exceptional, relates to the initial organisms, the first plant, fish, bird, and beast, upon which hereditary propagation must have subsequently succeeded. That these original pairs should have been evolved out of the potency of matter without parentage — that the matter, otherwise incapable of the task, should have been proximately disposed for such evolution — belongs to a special Divine Administration. In other words, God must have been the sole efficient cause — utilizing, of course, the material cause — of the organization requisite, and hence may strictly be said to have formed such pairs, and in particular the human body, out of the pre-existent matter (Harper, op. cit., 743). It need hardly be said that the distinctions between creation and co-operation, administration and formation, are not to be considered as subjectively realized in God.

Even if one construes the above passage in the most evolution-friendly way possible, it is clear that the author envisages the process by which the first organisms of each natural kind appeared as being entirely the work of God, Who “proximately disposed” the matter required for such evolution, as matter, by itself, was “otherwise incapable of the task.”

The Flood

Again, as regards the story of the Flood in Genesis, there was little to distinguish Bryan’s position from that of the Catholic Church: both insisted that at some point in history, there had been a universal Flood, of which Noah and his family in the Ark were the sole human survivors, but neither Bryan nor the Catholic Church accepted the literal chronology of Genesis. Bryan, in his testimony at the Scopes Trial, stated that he believed in a “literal interpretation” of the Flood story in Genesis, but explicitly rejected Archbishop Ussher’s estimate of the date of the Flood at 2,348 B.C., declaring, “I would not say it is accurate.” For its part, the Catholic Encyclopedia, in its 1908 article on the Deluge, insisted that the Flood “must have destroyed the whole human race” even if it did not cover the whole Earth, but declared that “there is nothing in the teaching of the Bible preventing us from assigning the Flood to a much earlier date than has usually been done.”

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia article on the Deluge:

As to the view of Christian tradition, it suffices to appeal here to the words of Father Zorell who maintains that the Bible story concerning the Flood has never been explained or understood in any but a truly historical sense by any Catholic writer (cf. Hagen, Lexicon Biblicum)…

The Biblical account ascribes some kind of a universality to the Flood. But it may have been geographically universal, or it may have been only anthropologically universal. In other words, the Flood may have covered the whole earth, or it may have destroyed all men, covering only a certain part of the earth…

Science, therefore, may demand an early date for the Deluge, but it does not necessitate a limitation of the Flood to certain parts of the human race…

Up to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the belief in the anthropological universality of the Deluge was general. Moreover, the Fathers regarded the ark and the Flood as types of baptism and of the Church; this view they entertained not as a private opinion, but as a development of the doctrine contained in 1 Peter 3:20 sq. Hence, the typical character of both ark and Flood belongs to the “matters of faith and morals” in which the Tridentine and the Vatican Councils oblige all Catholics to follow the interpretation of the Church.

Genesis places the Deluge in the six-hundredth year of Noah; the Masoretic text assigns it to the year 1656 after the creation, the Samaritan to 1307, the Septuagint to 2242, Flavius Josephus to 2256. Again, the Masoretic text places it in B.C. 2350 (Klaproth) or 2253 (Lüken), the Samaritan in 2903, the Septuagint in 3134. According to the ancient traditions (Lüken), the Assyrians placed the Deluge in 2234 B.C. or 2316, the Greeks in 2300, the Egyptians in 2600, the Phoenicians in 2700, the Mexicans in 2900, the Indians in 3100, the Chinese in 2297, while the Armenians assigned the building of the Tower of Babel to about 2200 B.C. But as we have seen, we must be prepared to assign earlier dates to these events.

Joshua

Bryan was subjected to ridicule when cross-examined by Clarence Darrow, for upholding the historicity of the miracle in the book of Joshua, where the sun appeared to stand still in the sky. Bryan stated his belief that the Earth had stopped rotating at God’s command, and that God, in his omnipotence, was perfectly capable of protecting the planet from any harmful consequences that might result if this were to happen. The Catholic Church took much the same view: as the Catholic Encyclopedia pointed out in its article on Joshua, “The Biblical Commission (15 Feb., 1909) has decreed the historicity of the primitive narrative of Genesis 1-3; a fortiori it will not tolerate that a Catholic deny the historicity of Josue [Joshua]. The chief objection of rationalists to the historical worth of the book is the almost overwhelming force of the miraculous therein; this objection has no worth to the Catholic exegete.”

Jonah

Finally, the Catholic Church, like Bryan, taught that Jonah was a real person, who had indeed been swallowed by either a whale or a great fish. As the Catholic Encyclopedia put it in its article on Jonah, “Catholics have always looked upon the Book of Jonah as a fact-narrative.”

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia article on Jonah:

Catholics have always looked upon the Book of Jonah as a fact-narrative. In the works of some recent Catholic writers there is a leaning to regard the book as fiction. Only Simon and Jahn, among prominent Catholic scholars, have clearly denied the historicity of Jonah; and the orthodoxy of these two critics may no longer be defended: “Providentissimus Deus” implicitly condemned the ideas of both in the matter of inspiration, and the Congregation of the Index expressly condemned the “Introduction” of the latter.

Reasons for the traditional acceptance of the historicity of Jonah:

Jewish tradition

According to the Septuagint text of the Book of Tobias (xiv, 4), the words of Jonah in regard to the destruction of Ninive are accepted as facts; the same reading is found in the Aramaic text and one Hebrew manuscript…

The authority of Our Lord

This reason is deemed by Catholics to remove all doubt as to the fact of the story of Jonah. The Jews asked a “sign” — a miracle to prove the Messiahship of Jesus. He made answer that no “sign” would be given them other than the “sign of Jonah the Prophet… He argues clearly that just as Jonah was in the whale’s belly three days and three nights even so He will be in the heart of the earth three days and three nights. If, then, the stay of Jonah in the belly of the fish be only a fiction, the stay of Christ’s body in the heart of the earth is only a fiction…

The authority of the Fathers

Not a single Father has ever been cited in favor of the opinion that Jonah is a fancy-tale and no fact-narrative at all. To the Fathers Jonah was a fact and a type of the Messias, just such a one as Christ presented to the Jews…

After having uncovered these six journalistic bombshells, I was left with a question. “Why hasn’t Mencken’s mendacity about the Scopes trial been publicly exposed?” I wondered.

The answer, it seems, is that Mencken is still regarded as a hero of free speech by the so-called “intelligentsia” and by the mainstream media. The official version of the Scopes trial is that Mencken was a Fearless Crusader for Truth and Justice in his reports for the Baltimore Evening Sun, and that William Jennings Bryan was an ignorant religious bigot. To overturn that version of events would mean admitting that the media had gotten it wrong, for 88 years.

In my upcoming post, to be published next week, I will document nine lies Mencken told, relating to the Scopes trial. Stay tumed!