|

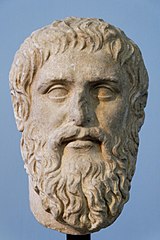

The philosopher Plato wrote in his work, Phaedrus, that successful theories should “carve nature at its joints.” Scientists have a special obligation to abide by this maxim, since the stated aim of science is to systematically describe Nature, as she really is. The worst kind of intellectual crime I can conceive of would be the imposition on the populace of a conceptual system which fails to carve Nature at its joints. When people are deceived into believing a false proposition, their error can be corrected by simply pointing out the truth; but when people are forced to adopt a totally wrong way of slicing and dicing reality, the very fabric of their thinking is warped, and intellectual progress is retarded. It may take several generations to undo the harmful effects of this socially imposed intellectual blindness.

Line, square, cube: The harm wrought by conceptual confusion in the physical, biological and social sciences

The Germans have a fine word – Weltanschauung – for a comprehensive conception of the world, and of our relation to it. It is in the social sciences that the harmful effects of a warped Weltanschauung are most severely felt. To adapt a metaphor from C.S.Lewis’s Perelandra: if we liken the harm done to society by imposing a fundamentally mistaken worldview in the physical sciences to a line, then the harmful effects of imposing a flawed concept of Nature in the biological sciences can be likened to a square, while the consequences of a warped Weltanschauung in the social sciences can be likened to a cube. If people living in a society are deceived into believing false ideas about the physical world, the worst thing that can happen to them is a sharp increase in the death rate (e.g. from famine or disease), which occurs when the world doesn’t behave in the way people would like it to. Mistaken ideas of this kind are quickly corrected and seldom forgotten. Conceptual errors in the biological sciences are more insidious, as they affect the way in which we relate to our fellow creatures, as well as the way in which we view ourselves. A society of people who adopt the Cartesian view that man is not an animal, but simply a res cogitans, may fail to recognize man’s place in natural ecosystems, and they may also be callously indifferent to the sufferings of other living things. At the other extreme, a society in which people are taught that man is just an animal may come to accept the lunatic proposition that the use of insecticides can be morally equated with homicide, or the paralyzing ethical principle that any kind of social project that harms other living creatures should be outlawed – which would leave us all living in grass huts. The social corruption resulting from warped views of man’s relations to his fellow creatures is more pernicious than that caused by adopting flawed systems in the physical sciences, because it is a kind of moral corruption. But the worst kind of social insanity is that which results when people are brainwashed into accepting false ideas about how human beings should relate to one another. The imposition of a flawed worldview in the social sciences is especially wicked, because it shatters the ties that bind us together. Ultimately, good habits are what holds society together – above all, the habit of performing little acts of kindness and decency towards those who are in need. These virtuous habits are carefully instilled in children by their parents and teachers. The terrible tragedy is that they can be destroyed in a single generation by the propagation of a pernicious worldview in the social sciences which renders us morally blind, leaving us unable to perceive people around us who are in need. Telling people that they are not free, and that their behavior is determined by circumstances beyond their control, weakens their ability to empathize with the suffering of others, because it provides them with the perfect excuse for ignoring the plight of the homeless, the sick and the needy: “I can’t help being the selfish person I am.” Tell a young man that the concept of private property is a creation of the class system, and he will feel no compunction about forcibly taking from others what he feels he has been deprived of, all his life – even if he has to take it at gunpoint. Tell a boy that “man” and “woman” are merely social categories, and the notion that hitting girls is an especially vicious and cowardly act which undermines the age-old principle of friendship between the sexes will no longer make sense to him. Tell a young girl that she can marry anyone she likes, and when she grows up, she will be incapable of grasping the wickedness of abandoning her husband (whom she no longer fancies) for a lesbian lover.

During the last few decades, psychologists have been attempting to hold a mirror up to our faces and tell us what human beings are really like, by informing us about the latest scientific findings in their field. I do not doubt their good intentions; but as they say, the road to Hell is paved with good intentions. As I see it, the danger of relying on the guidance of scientists is that scientific findings are always presented through the lens of a conceptual system – a particular way of seeing the world, or what the Germans call a Weltanschauung. If this Weltanschauung is all-pervasive, it is seldom challenged; people come to see the world through the medium of this universally accepted way of thinking, which they have been taught in schools and universities. Fish, it is said, are unaware of the water they swim in; it is all around them. Our way of “slicing and dicing” the world is the water we swim in: we may question some new idea that we hear of, but it seldom occurs to us to question the validity of our own fundamental categories. Scientists and educators who mold young and impressionable minds by training them to think in terms of these categories, therefore have a special responsibility not to exaggerate what they think they know. The consequences, particularly in the social arena, can be disastrous.

How the imposition of scientific dogmas puts science and society in a straitjacket

The point I want to make here is that any new branch of science takes a long while – typically a couple of hundred years – to find its conceptual feet. (To be perfectly clear: what I am talking about are the major branches of science, such as physics, chemistry, biology, geology, sociology and psychology, rather than about more specialized fields which fall under the umbrella of a larger discipline, in the way that the sciences of entomology falls under the umbrella of biology. Nor I am talking about new scientific disciplines created by the marriage of two existing disciplines.) During its first 200 years, a new branch of science enjoys a kind of heady freedom, in which it proposes and explores new concepts – most of them wildly mistaken – before arriving at a settled view as to how the objects which fall within its purview should be properly classified. What this means is that within a new branch of science, any conceptual schema which is currently in vogue is almost certainly wrong. Thus to take a conceptual schema from a new and unsettled science and to impose it on the general population as an established dogma is to commit an intellectual sin of the first order: it retards the progress of an emerging field of knowledge, and it ossifies our thinking, in a manner which may well turn out to be socially pernicious, and even dehumanizing, as we saw above.

I would like to illustrate my thesis by stepping back in time, to the glorious days of the Scientific Revolution, when several new fields of science emerged.

Why a new scientific discipline requires a long time to develop its fundamental concepts

|

|

Robert Boyle is generally regarded as the father of chemistry. The publication of his work, The Sceptical Chymist, in 1661, marks the beginning of chemistry as a science. But 147 years were to elapse before John Dalton published a full account of his atomic theory in 1808, and it was not until the publication of Mendeleev’s Periodic Table in 1869 that chemists arrived at a systematic understanding of their subject matter.

In the meantime, the science of chemistry made several wrong turns, owing to the proposal of plausible-sounding theories which later turned out to be unfruitful. One of these was phlogiston theory, a theory of combustion which was first suggested in 1667 by Johann Joachim Becher, formally propounded by Georg Ernst Stahl in 1703, and finally overturned by the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier, in the 1780s. (The theory proposed that a fire-like element called phlogiston is contained within combustible substances and released during combustion – which would imply, contrary to fact, that substances should lose weight, when they are being burned.) Phlogiston theory had highly respectable advocates, including Cavendish and Priestley: as commenter johnnyb points out below, it even appeared to be experimentally verifiable. [An online article published by the American Chemical Society describes one such test: “A typical test for the presence of phlogiston was to place a mouse in a container and measure how long it lived. When the air in the container could accept no more phlogiston, the mouse would die.”] Nevertheless, phlogiston turned out to be a scientific blind alley, which lasted for more than a century before it was successfully refuted.

The science of anatomy is even older than chemistry: it dates back to the publication of De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) by Vesalius in 1543. But it was not until 85 years later that doctors became aware of the heart’s role in the circulation of blood throughout the body, thanks to the indefatigable labors of William Harvey. (Other scientists had proposed the same idea previously, but their views had not been widely published.) And it was not until 1839, almost 300 years after the pioneering work of Vesalius, that Theodor Schwann and Matthias Jakob Schleiden managed to show that the bodies of plants and animals are actually made up of cells. Think about that. For three centuries, anatomists didn’t even know what the basic building blocks of the body were.

The science of psychology is a much younger discipline than chemistry or anatomy: its foundation is traditionally dated to 1879, with the establishment of the world’s first experimental psychology lab at the University of Leipzig by Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt. The science of sexology is younger still: its establishment as a scientific discipline dates back to 1886, with the publication of Richard Freiherr von Krafft-Ebing’s work, Psychopathia Sexualis. What that means is that a mere 130 years have elapsed since this “science” (if you want to call it that) was founded.

Had sexology followed the historical trajectory of chemistry, then its scientific proponents would still be wandering in the dark, lacking even the basic concepts which were later to define their field. In order to appreciate this point, try a little thought experiment, and ask yourselves: how much did chemists really know about matter, back in 1791, when their science was but 130 years old? Not a whole lot: the law of conservation of mass had been propounded by Antoine Lavoisier only a few years before, in 1785 (although several scientists had suggested it earlier), and he had only recently demonstrated that oxygen and hydrogen were elements, in 1778 and 1783, respectively. Strangely, Lavoisier also regarded heat and light as chemical elements: he coined the term “caloric” for the element of heat, which he regarded as an invisible fluid which flowed from a hot body to a cooler one. In Lavoisier’s day, less than a score of the 118 elements now known to science had been identified.

Readers may argue that there has been a “knowledge explosion” in the last 100 years, and that the now-universal acceptance of the scientific method enables researchers to falsify bad hypotheses much more quickly than was possible in times past. On this logic, we should expect new sciences, such as psychology and sexology, to mature much more quickly than their 17th century forebears, such as physics and chemistry. Putting it another way: science has a learning curve.

I beg to disagree. While there exists abundant evidence for a learning curve (or “knowledge explosion”) within various scientific disciplines, I know of no good evidence to support the claim that the newer branches of science have managed to refine their key concepts more quickly than the older ones did. Testing can eliminate a false hypothesis, but it cannot create a correct worldview. My contention is that a long period of wild speculation, vigorous debate and conceptual chaos should be regarded as a normal and healthy symptom of the emergence of any new branch of science. One should not try to hasten this process, as the imposition of uniformity can only be achieved by clipping the academic wings of bold thinkers with creative insight. It is thinkers like these who make the emergence of a new field of science possible in the first place, and it is only within a “no-holds-barred” academic environment, where no idea is considered taboo, that genuine progress can be made by these independent minds, in the task of formulating fundamentally new concepts.

Some examples of dogmatism in the field of sex research

|

|

If the foregoing analysis is correct, then the categories currently being used by practitioners of a 130-year-old infant science, such as sexology, should be taken with a very large grain of salt. Nor will it help matters if we try to re-classify this new science as a mere specialization, falling under the umbrella of the larger scientific discipline of psychology. For as we saw above, the science of psychology is scarcely any older, dating back a mere 137 years.

Which brings us to the currently fashionable categories of sexuality and gender, neither of which is to be confused with an individual’s biological sex. Sexuality, as a popular adage has it, refers to who you want to go to bed with, while gender refers to who you go to bed as. We are also told that human sexuality falls along a continuous spectrum, and that very few people are exclusively heterosexual or homosexual. Sexuality is also defined as an orientation towards individuals belonging to a certain group: a homosexual is attracted to individuals of the same sex, while a heterosexual is attracted to persons of the opposite sex.

Gender is sharply distinguished from sex: the latter is a biological reality, while the former is a social construct. People may psychologically identify with individuals of a different biological sex; such individuals are said to be transgender, while those who identify with their own biological sex are referred to as cis-gender.

Now, if these ideas were being proposed as tentative hypotheses in the halls of academia, I would have no objection to their being freely discussed. But I read of these categories being rammed down the throats of six-year-old children, then I have to put up my hand and say, “Stop!” For the reality is that these categories, which are currently being proposed by psychologists, turn out to quickly crumble, when subjected to scrutiny.

Take the notion, popularized by Alfred Kinsey, of a spectrum or continuum of human sexuality. If Kinsey’s notion of a continuum were correct, then we would expect to find most people somewhere in the middle. At the very least, we would expect to find people occupying every shade of sexuality from heterosexual to homosexual. But a recent study conducted by Washington State University (WSU) and University of Southern Mississippi refutes the continuum model, lending support instead to a “taxonic” model, in which there are discrete categories of individuals, with distinct orientations. The study found no evidence of a significant overlap between heterosexuals and homosexuals. What’s more, after conducting interviews with 35,000 adults, the study found that a mere 3 percent of men and 2.7 percent of women are not heterosexual. Some continuum!

Or take the notion of sexual orientation. The underlying metaphor here is that of a compass: some people’s compasses point them towards individuals of the same sex, while other people’s compasses point them towards individuals of the opposite sex. But on that model, what are we to make of bisexuals? A compass cannot point in two directions at once. Or do these individuals have two compasses?

Or again, what are we to make of the phenomenon of asexuality, which is estimated to affect around 1% of the population? Are we supposed to believe that asexuals have a broken compass? That sounds rather patronizing, doesn’t it?

We are told that one’s sexual orientation is part of one’s sexual identity: it is said to be a fixed trait, resistant to any attempts at “conversion therapy.” (This piece of dogma completely overlooks scientific evidence that individuals’ sexuality frequently changes during adolescence, for no apparent reason, although it is far less amenable to change when people reach their twenties.) But what I find very curious is that other sexual predilections, such as fetishes and paraphilias, are not said to constitute part of one’s identity, even though they may be equally fixed. What’s the logic underlying this distinction? Is there any?

As someone who is familiar with the history of Greek philosophy, I cannot help but notice the essentialism underlying theories of people having fixed orientations. The implicit notion here is that your sexual orientation is part of your very essence, and that any attempt to change it is not only futile, but unnatural. What I find astonishing is that the very scientists who defend the Aristotelian-Platonic notion of essence in the sexual realm are apt to ridicule it when discussing evolutionary biology. The notion that species have a fixed essence which distinguishes them from other species is regarded as having been totally discredited, following the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859. Why, then, is there such uncritical acceptance of the idea that individuals have an unalterable essence, in the field of sex research?

Or take the notion of gender. Currently, the American public is being harangued by judges, politicians and “enlightened” government officials telling them that people should be allowed to use the bathrooms corresponding to the sex they identify with. The idea is that it is your feelings (and not your biological make-up) which determine your identity as a man or woman. If you feel like a woman, then you are a woman. Simple as that. Why, then, do we not use the maxim, “If you feel like an X, then you are an X,” in other areas of daily life? If you feel like a rocket scientist, then you are a rocket scientist. (Let’s see what NASA has to say about that.) If you feel like a Frenchman, then you are a Frenchman. (Try telling that to the people at the French embassy, and see if they’ll grant you natural citizenship.) And if you feel as if you’re grotesquely overweight, then you are overweight. On that logic, anorexia is no longer a disease: anorexics perceive themselves truly.

The American public have been told that there are two genders, but people are gradually coming to realize that this is an oversimplification. “Genderqueer” individuals may consider themselves to be members of a third gender. Alternatively, they may have two or more genders, or they may feel that they have no gender at all. Or they may have a fluctuating gender identity, making them genderfluid. Which toilet, we may ask, are these people supposed to use? Perhaps it is time to introduce single-user toilets everywhere: that would defuse the controversy.

If the notion of “gender” has any validity, then we would expect it to be found in the vast majority of human cultures. And indeed, there are many cultures around the world in which individuals can be found who fall outside the behavioral norms for their sex. In some societies, this breach of sexual stereotypes is deftly handled by creating a special social category for people who want to behave in a manner which is more typical of the opposite sex. But it would be totally unwarranted to infer that men in these societies who prefer to adopt a female sex role literally see themselves as women, or vice versa. What Western social scientists are doing here is imposing their own categories on people of other cultures. The reality is not that simple.

Some years ago, I recall hearing about a special category of men in Japan (where I live) who behave in an overtly effeminate manner. Were they gay, I asked? No. Were they transvestites? No. Were they trans-sexuals? No. None of our Western categories were capable of pigeon-holing these men.

And speaking of cultural diversity, what are we supposed to make of the Bugis culture of Sulawesi, Indonesia, which has been described as having three sexes (male, female and intersex) as well as five genders, with distinct social roles? Enormously complicates the picture, doesn’t it?

I haven’t really been trying to discredit these notions of orientation, gender and a continuum, which are currently in vogue among sexologists. I’ve just been raising doubts, which should make us pause before we rush head-long into embracing these newfangled concepts. Precisely because they are relatively new, they are probably wrong. And for precisely that reason, the attempt to impose them on our children as “settled science” is especially pernicious. I would go so far as to call it a sin.

Children today – and college students as well – are presented with concepts such as “sexual orientation” and “gender,” without having any opportunity to question the validity of these notions. Indeed, they are not told that there is anything to question: the concepts are treated with the same degree of deference shown to the concept of gravity. And while we’re on the subject of gravity, let us recall that a full 228 years elapsed between its original proposal by Newton in 1687, and its theoretical explanation by Einstein in 1915 – a fact that should give us pause, and cause us to ask ourselves whether the mass indoctrination of our children with concepts that are only a few decades old is such a good idea after all. Permit me to make one more unfavorable comparison: the concept of gravity may have been deeply mysterious in Newton’s day, but at least it had the virtue of being experimentally demonstrable and quantifiable – features which most scientific concepts in the social sciences still lack. Why, then, is society engaging in a head-long rush to judgement, in endorsing these concepts?

A little wager

Before we impose these new-fangled psychological categories on our children, I would invite readers to take me up on a little wager. Imagine that you could be transported to the year 2516, 500 years into the future. If they still have schools then, it’s a pretty safe bet that children learning chemistry will still learn about atoms, and that children studying biology will be taught about cells. Who wants to bet that children studying psychology will still be taught about the concepts of sexuality or gender? I certainly wouldn’t consider that a safe bet. Why, then, are we indoctrinating children in these concepts today, as if they were settled science?

Conclusion

The effects of this mass indoctrination in the social arena will be felt for generations to come. The results are becoming apparent, even now. The two sexes will become strangers to each other, with men having no idea how to date women, and vice versa. The social institutions which formerly held society together – especially the nuclear family – will become steadily less prevalent, and will eventually come to be seen as oddities. New institutions – namely, ones which are more readily brought under government control – will take their place. Child-rearing will eventually become communal, as envisaged in Plato’s Republic, and children will grow up never knowing what it is like to have two people who love them more than anyone else in the world, and whom they can love back with the same unconditional devotion. The world that awaits us may turn out to be a more prosperous world, materially speaking. But it will certainly be a less human world. And it is being created now, in our schools and in our halls of academia. I ask: if this is not a crime, then what is?