In “Pregnant 9/11 survivors transmitted trauma to their children” (The Guardian, September 12, 2011), Mo Costandi tells us,

The emerging field of epigenetics shows how traumatic experiences can be transmitted from one generation to the next.

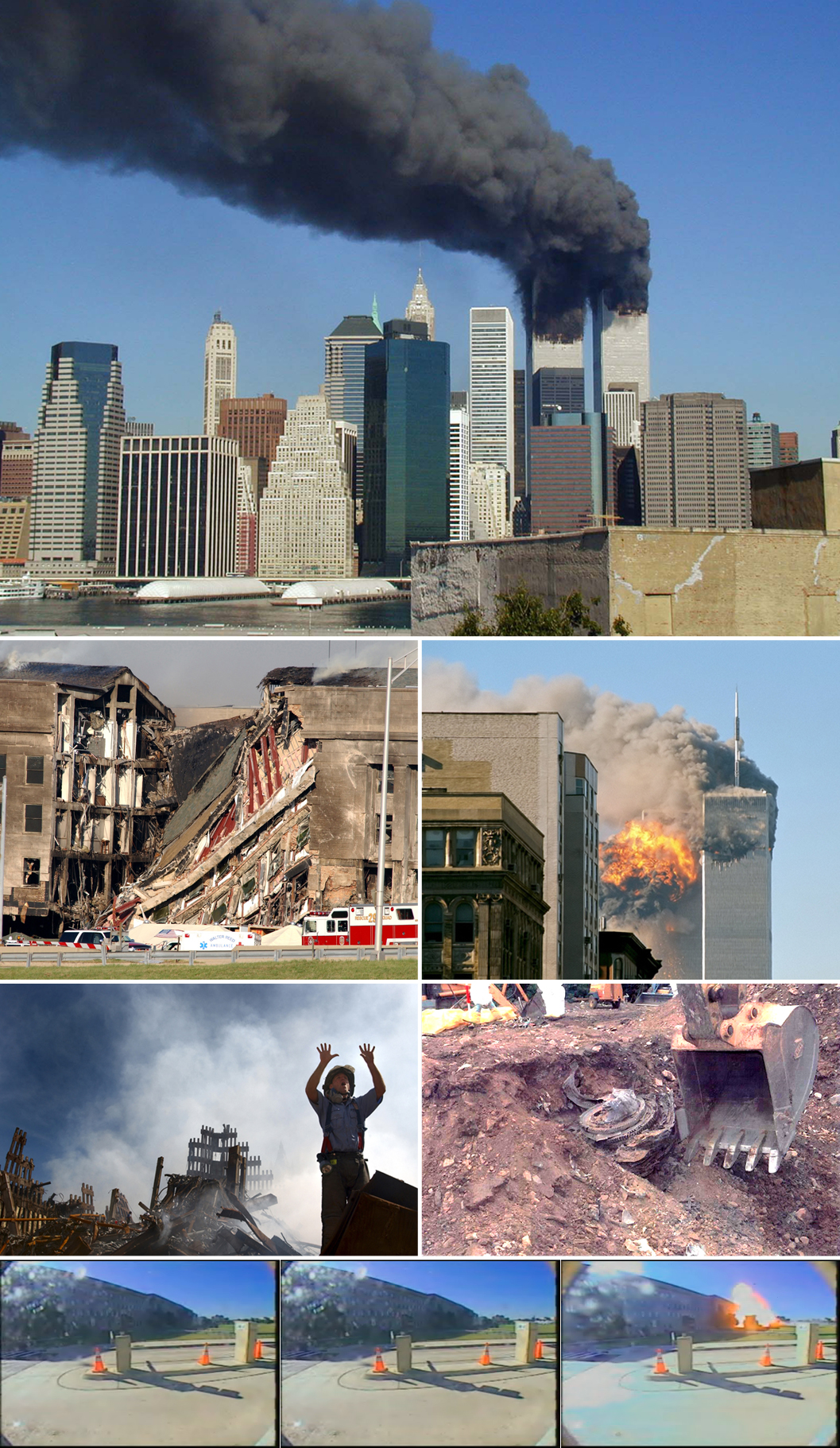

Studying pregnant women who had been in the 9-11 vicinity and showed symptoms of trauma,

Yehuda and her colleagues performed a longitudinal study. They recruited 38 women who were pregnant on 9/11 and were either at or near the World Trade Centre at the time of the attack, some of whom went on to develop PTSD. The researchers took samples of saliva from them and measured levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

They found that those women who had developed PTSD following exposure to the attacks had significantly lower cortisol levels in their saliva than those who were similarly exposed but did not develop PTSD. About a year later, the researchers measured cortisol levels in the children, and found that those born to the women who had developed PTSD had lower levels of the hormone than the others. Intriguingly, reduced cortisol levels were most apparent in those children whose mothers were in the third trimester of pregnancy when they were exposed to the attack.

That is interesting because, in general, acquired birth defects are most pronounced if acquired early in gestation.

The mechanism? Rat studies showed that

these effects are mediated by epigenetic mechanisms that alter expression of the glucocorticoid receptor, which plays a key role in the body’s response to stress. Analysis of the pups’ brains at one week old revealed differences in DNA methylation, a process by which DNA is chemically modified. Methylation involves the addition of small molecules called methyl groups, consisting of one carbon and three hydrogen atoms, to specific sites in the DNA sequence encoding a gene.

Is this a signal? Or just more noise in a noisy world full of anxiety?

An attractive feature of epigenetics, if these results hold up, is that it would help explain a long-standing puzzle: The children, even grandchildren, of trauma survivors often seem a bit damaged themselves. “Oh, it’s just psychological,” everyone says, “He grew up knowing that his mom had been kidnapped by the White Lake killer while she was pregnant with him, and rescued by a sniper squad.” Well, no doubt it’s psychological. But if epigenetics is right, it could be more than that. The experience might have changed his metabolism in certain ways. In which case, epigenetics can help guide treatment, if needed.

See also: Fed up with the Gene vs. Scene war? All together now: E-P-I-G-E-N-E-T-I-C-S Rules!

Follow UD News at Twitter!

Hat tip: Stephanie West Allen at Brains on Purpose